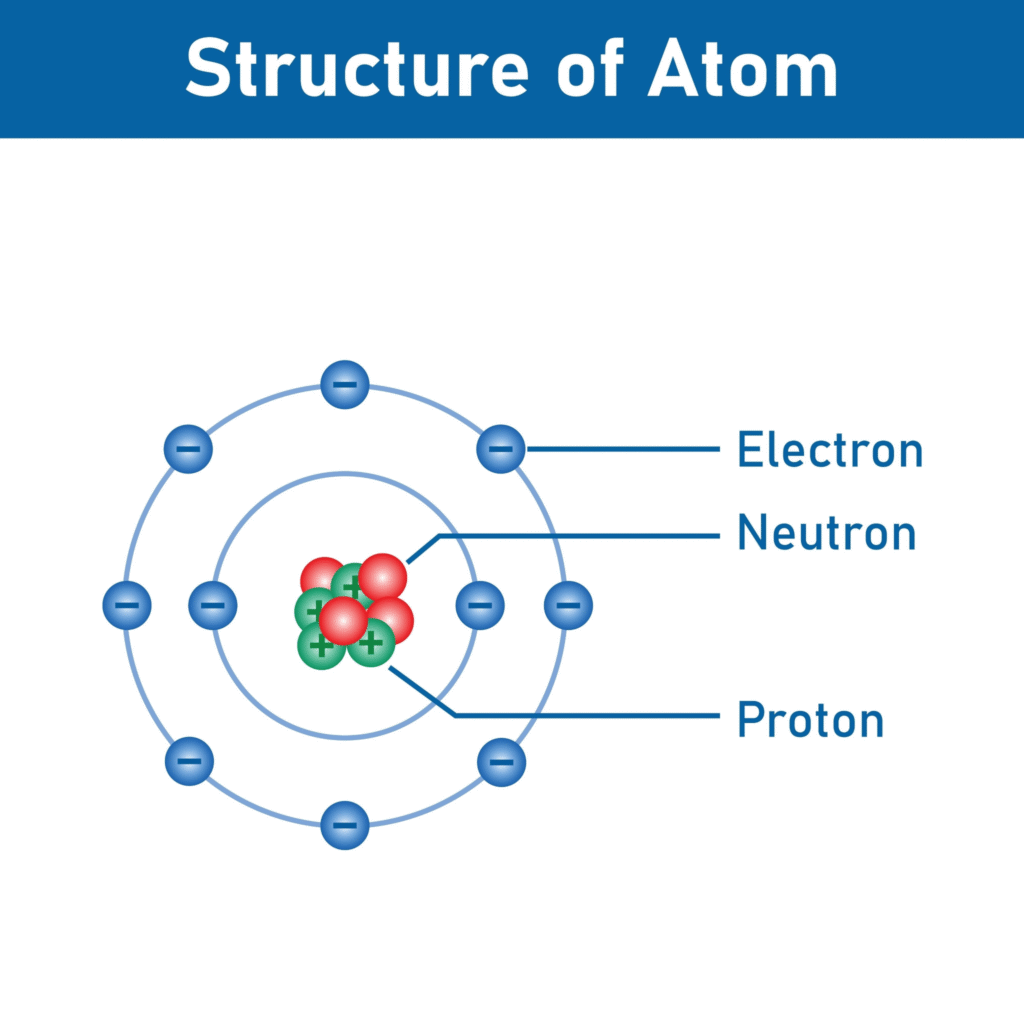

The foundation of all matter lies in the atom, which is composed of a central nucleus and orbiting electrons. The nucleus contains positively charged protons and neutral neutrons, and it houses nearly all the atom’s mass. Surrounding this core are electrons, which are negatively charged particles moving in specific regions called shells or energy levels. Each shell has a defined capacity for holding electrons, with the innermost K shell holding a maximum of two, the L shell holding eight, and so on. The unique identity of an element is determined by its atomic number, which is the number of protons (and usually an equal number of electrons in a neutral atom). For an atom to be stable and non-reactive, it aims to have its outermost electron shell completely filled, a state known as having a complete valence shell, similar to the noble gases.

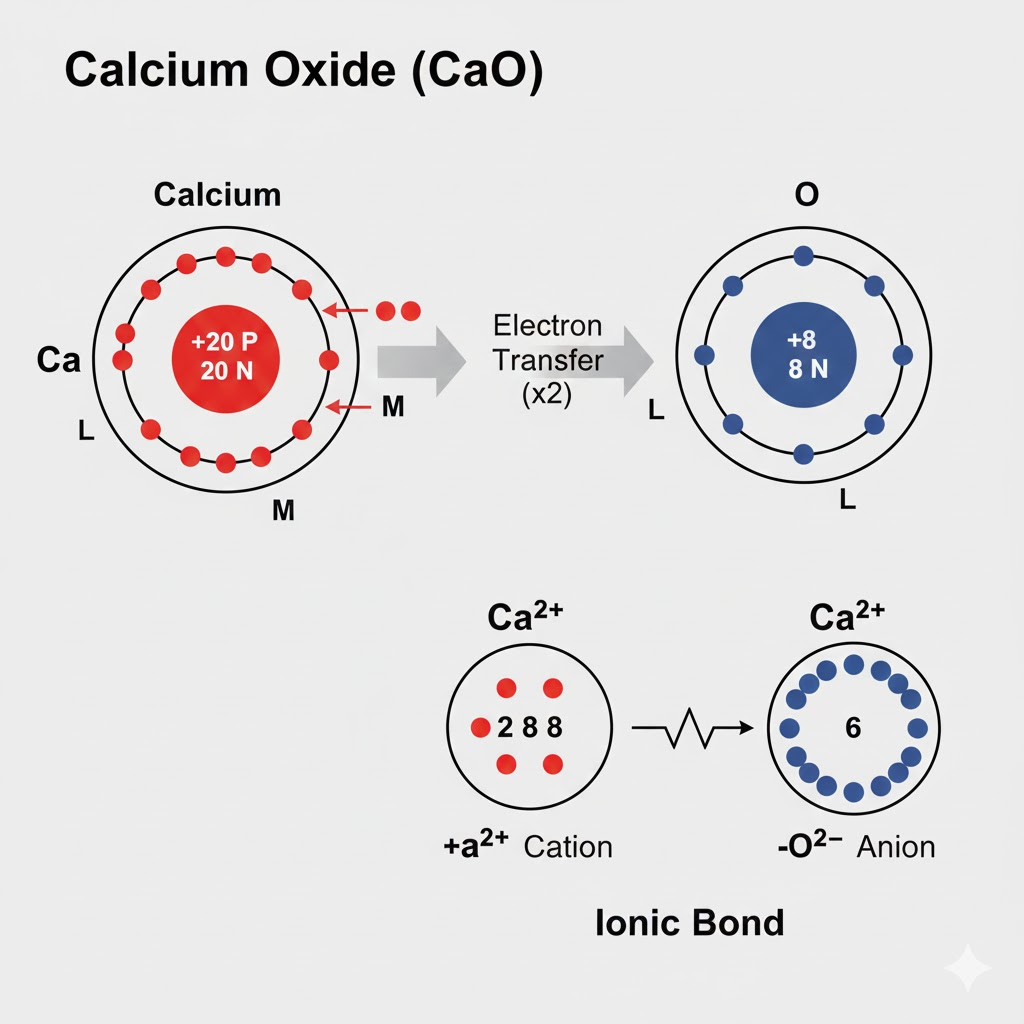

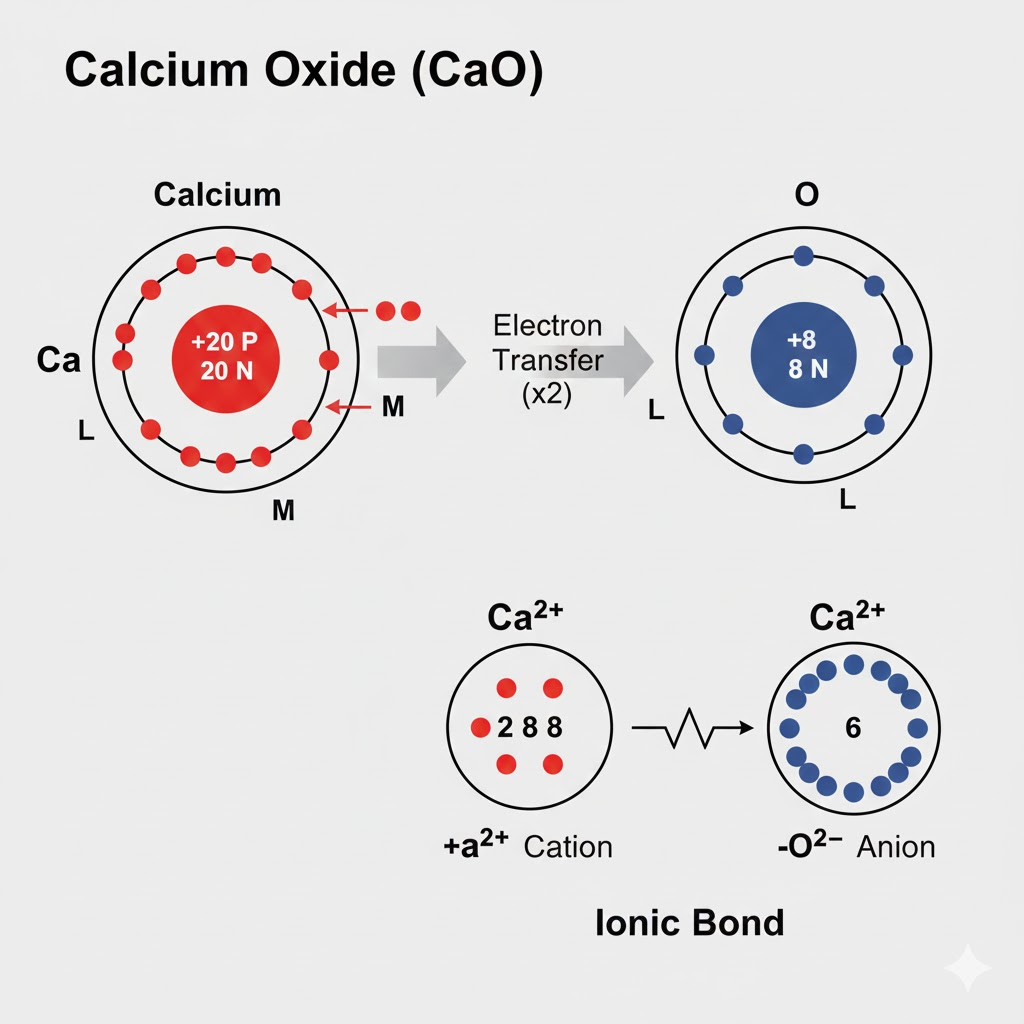

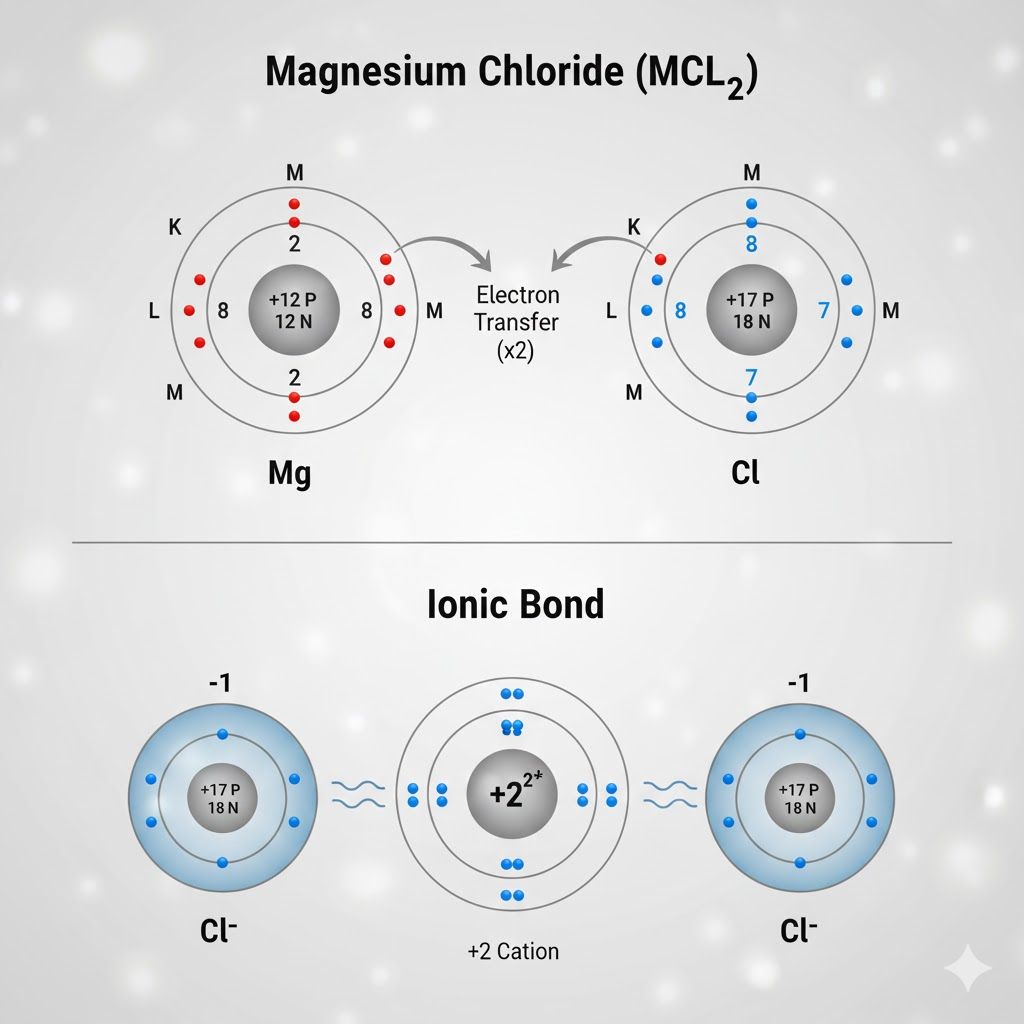

Since most atoms do not naturally possess a stable electron configuration, they undergo chemical bonding to achieve it. The primary driver of this bonding is the attraction between atoms that allows them to share or transfer electrons. The chapter details two fundamental types of bonds. This transfer creates positively charged ions (cations) and negatively charged ions (anions), which are then held together by strong electrostatic forces. This commonly occurs between metals, which tend to lose electrons, and non-metals, which tend to gain them.

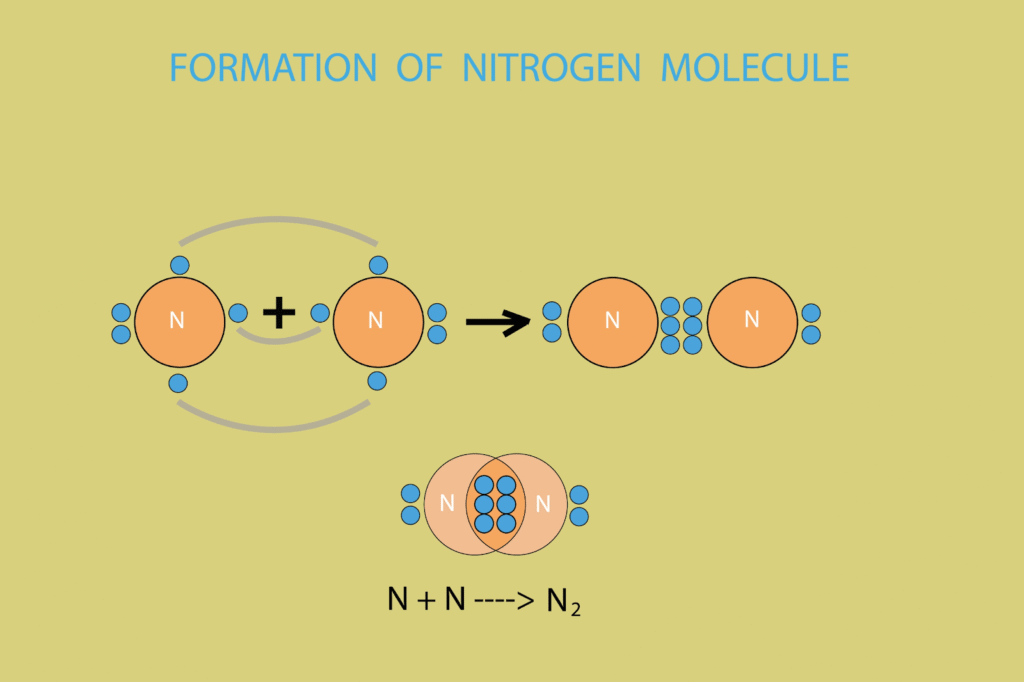

The second major type is the covalent bond, which is highly relevant to biological molecules. Instead of transferring electrons, atoms form a covalent bond by sharing one or more pairs of electrons between them. This sharing allows each atom to effectively complete its outer shell. A single bond involves one shared pair, a double bond involves two, and a triple bond involves three. Molecules like hydrogen, oxygen, and water, along with vast organic compounds like glucose, are all held together by these strong covalent bonds. Understanding these atomic interactions is crucial in biology because the structure and properties of essential molecules—from DNA and proteins to carbohydrates—are a direct result of the chemical bonds that form them.

Exercise 4 (A)

Question 1.

1. What is the contribution of the following in atomic structure? Maharshi Kanada

2. What is the contribution of the following in atomic structure? Democritus

Ans:

1. Contribution of Maharshi Kanada to Atomic Structure

Maharshi Kanada, an ancient Indian philosopher and sage, is a foundational figure in the history of atomic theory. His contributions, articulated centuries before similar ideas emerged in the West, are found in the Vaisheshika Sutra, a text rooted in Hindu philosophy.

Kanada’s primary contribution was the formulation of the concept of the “Anu” (Sanskrit for “atom”). His thinking was not experimental but was a profound philosophical and logical deduction about the nature of reality. His key ideas include:

- The Indivisible Particle (Anu): Kanada proposed that every object in the physical universe is made of a finite number of Anu. He argued that if one continuously divides a substance, a point is reached where it can no longer be split further. This ultimate, indivisible particle was the Anu. This is a direct parallel to the modern definition of an atom.

- Eternal and Unchangeable Nature: He postulated that these Anu are eternal, indestructible, and exist beyond the perception of the human senses. They were the building blocks of all matter, including the elements like earth, water, fire, and air.

- Diversity of Matter: Kanada brilliantly explained the vast diversity of the material world by proposing that Anu of different substances are inherently distinct in their properties (e.g., an earth Anu is different from a water Anu). Furthermore, he suggested that combinations of different types and numbers of Anu create the complex materials we perceive.

- The Role of Heat: He introduced the concept of “heat” as a catalyst for change, suggesting that the interaction and combination of Anu were influenced by it, a primitive foreshadowing of the role of energy in chemical reactions.

In essence, Maharshi Kanada’s contribution was the world’s first systematic, philosophical argument for atomism. He provided a logical framework for understanding the material world as being composed of tiny, indivisible, and eternal particles, laying a conceptual groundwork that was remarkably prescient.

2. Contribution of Democritus to Atomic Structure

Democritus, an ancient Greek philosopher often called the “Father of Atomism,” developed his theory around the same era as Kanada, though independently. His ideas, while also philosophical, were a radical departure from the continuous-matter theories of his contemporaries like Aristotle.

Democritus’s central contribution was his theory of the “Atomos” (Greek for “uncuttable” or “indivisible”). His reasoning was based on the philosophical problem of change and permanence in the universe. His core principles were:

- The Void and the Atom: Democritus asserted that the universe consists of only two fundamental realities: the void (empty space) and an infinite number of atoms. He argued that motion and change are impossible without the void, as atoms need empty space to move and interact.

- Intrinsic Properties of Atoms: He theorized that all atoms are made of the same fundamental substance but differ in their physical properties, which he defined by their shape, size, and arrangement. For example, he described fire atoms as sharp and prickly, while water atoms were smooth and slippery. The different sensory properties of materials (sweet, bitter, hard, soft) arose solely from the geometric configurations of their constituent atoms.

- Mechanical and Deterministic Universe: Democritus envisioned a universe governed by mechanical laws, not divine whims. He believed atoms moved, collided, and hooked together in the void entirely through natural, deterministic causes, forming the complex world we see. This was a crucial step towards a scientific, rather than a mythological, understanding of nature.

Question 2.

State Dalton’s atomic theory.

Ans:

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, John Dalton, an English scholar, put forward a groundbreaking conceptual framework that would become the bedrock of modern chemistry. His Atomic Theory proposed that all matter is ultimately composed of minute, indestructible units called atoms. He reasoned that every element is defined by its own unique type of atom, each possessing a specific mass and set of properties. When these distinct atoms combined in fixed, simple proportions, they gave rise to chemical compounds. This idea provided a clear, particulate explanation for the natural world.

A central pillar of Dalton’s theory was its explanation of chemical reactions. He posited that such reactions are not the creation or annihilation of atoms, but merely their reorganization into new combinations. This perspective gave solid theoretical backing to the already observed Law of Conservation of Mass, confirming that the total mass remains constant during a chemical change. Although subsequent scientific discoveries, such as the existence of electrons and protons, revealed that atoms are indeed divisible, this does not diminish the theory’s monumental impact. Dalton’s work successfully moved the atom from philosophical speculation to a concrete, scientific entity that could be used to predict and rationalize chemical behavior.

Question 3.

What is an 𝛼 (alpha) particle?

Ans:

An alpha particle is a specific type of nucleus emitted by certain unstable, heavy elements like radium or uranium during a process known as radioactive decay. In terms of its composition, it is identical to the nucleus of a helium atom. This means it is made up of two protons and two neutrons tightly bound together. Because of this structure, it carries a positive charge of +2, as the two protons contribute their positive charges while the neutrons are neutral.

Due to its relatively large mass and double positive charge, an alpha particle has a very short range and low penetrating power. It can be stopped by something as thin as a sheet of paper or even the outer layer of human skin. However, despite this weak penetration, alpha particles are highly ionizing. This means that as they travel, they forcefully knock electrons away from any atoms they pass near, creating a trail of ion pairs. If an alpha-emitting substance is ingested or inhaled, this intense ionization can cause significant damage to living tissue, making it dangerous despite its inability to penetrate the skin externally.

Question 4.

What are cathode rays? How are these rays formed?

Ans:

Cathode rays are streams of fast-moving, negatively charged particles that originate from the cathode, or the negative electrode, inside a specially designed glass tube known as a discharge tube. This tube has a very low pressure, almost a vacuum, with a trace amount of gas like air or hydrogen. When a very high electrical voltage, typically thousands of volts, is applied across the two metal electrodes sealed in the tube, the gas inside, which is normally an insulator, becomes a conductor of electricity. It is at this moment that a glow emerges from the cathode and invisible rays travel in straight lines towards the anode, the positive electrode. These are the cathode rays.

The formation of these rays is a direct result of the ionization of the gas atoms within the tube. The immense electrical force rips electrons away from the gas atoms, creating a mixture of positive ions and free electrons. The positive ions are powerfully attracted to the negatively charged cathode and crash into its surface. This violent bombardment of the cathode plays the most critical role, as it literally knocks electrons out from the metal of the cathode itself. These newly liberated electrons are then violently repelled by the negative cathode and are simultaneously pulled at high speed towards the positive anode. Since the tube is nearly evacuated, these electrons can race across the tube without colliding with many gas atoms, forming a focused beam of what we identify as cathode rays

Question 5.

1. What is the nature of the charge on Cathode rays?

2. What is the nature of the charge on Anode rays?

Ans:

1. What is the nature of the charge on Cathode rays?

Cathode rays are fundamentally composed of a stream of fast-moving electrons. As the electron is a fundamental subatomic particle, it carries a negative electrical charge. This negative nature is conclusively demonstrated by their behavior in electric and magnetic fields; the rays are unequivocally deflected towards the positively charged plate. Therefore, the intrinsic nature of the charge on cathode rays is negative.

2. What is the nature of the charge on Anode rays?

Anode rays, also referred to as canal rays, are composed of positive ions originating from the gaseous atoms within the discharge tube. When electrons from the cathode rays collide with these gas atoms, they knock other electrons out of their orbits. The resulting leftover atom, now missing one or more electrons, possesses a net positive charge. The specific value of this positive charge is dependent on the elemental nature of the gas and how many electrons were removed. Consequently, the fundamental nature of the charge on anode rays is positive.

Question 6.

How are X-rays produced?

Ans:

- Generate Electrons: A heated filament (the cathode) boils off electrons, creating a cloud of negatively charged particles.

- Accelerate Electrons: A powerful electric field (thousands of volts) violently accelerates these electrons across the vacuum tube towards a metal target (the anode), typically made of tungsten.

- Sudden Stop and Energy Conversion: When these high-speed electrons slam into the anode, they stop abruptly. Their immense kinetic energy is instantly converted. About 1% transforms into X-ray photons, while the other 99% becomes heat.

Question 7.

Why are anode rays also called ‘canal rays’?

Ans:

The name “canal rays” originates directly from the specific experiment conducted by the German scientist Eugen Goldstein in 1886. He used a cathode ray tube, similar to the one J.J. Thomson later used for electrons, but with a crucial modification: the cathode (the negative electrode) was perforated with holes, or channels. When a high voltage was applied across the tube, glowing rays were seen traveling away from the positively charged electrode (the anode), which was placed behind the cathode. These rays streamed in a straight line in the opposite direction of the cathode rays.

The most distinctive visual observation was that these rays passed through the holes or channels in the cathode. As they emerged on the other side of these perforations, they produced a glowing effect. Because they seemed to flow through these canal-like passages, Goldstein named them “Kanalstrahlen,” which translates directly from German to English as “canal rays.” So, the term is purely descriptive of their behavior in the original experimental setup, distinguishing them from the cathode rays that moved from the negative electrode to the positive one.

Question 8.

How do cathode rays differ from anode rays?

Ans:

Cathode Rays:

- Origin: Emanate from the cathode (negative electrode).

- Nature: A stream of negatively charged particles (electrons).

- Mass: Mass is fixed, equal to the mass of an electron.

- Composition: Identical in all gases, as they are just electrons.

- Deflection: Are deflected towards the positive plate in an electric field.

Anode Rays (Canal Rays):

- Origin: Emanate from the anode (positive electrode) through holes (canals) in the cathode.

- Nature: A stream of positively charged particles (ions).

- Mass: Depends on the gas used in the tube; it’s the mass of the gas atom minus an electron.

- Composition: Varies with the nature of the gas inside the tube.

- Deflection: Are deflected towards the negative plate in an electric field.

Question 9.

State one observation which shows that an atom is not indivisible.

Ans:

One clear observation that demonstrates an atom is not indivisible is the phenomenon of static electricity. For instance, when a plastic comb is rubbed vigorously through dry hair, it becomes capable of attracting small pieces of paper. This happens because the rubbing action causes tiny, negatively charged particles, later identified as electrons, to be transferred from the hair to the comb. The comb ends up with an excess of these particles, becoming negatively charged, while the hair, having lost them, becomes positively charged. This transfer and separation of a fundamental, sub-atomic component (the electron) proves that the atom is not a single, indivisible particle but is composed of smaller, constituent parts that can be separated from it.

Question 10.

1. Name an element which does not contain neutrons.

2. If an atom contains one electron and one proton, will it carry as a whole is neutral

Ans:

1. Name an element which does not contain neutrons.

The element is hydrogen, but more specifically, its most common isotope called protium.

In the nucleus of a typical hydrogen atom (protium), you will find a single proton and no neutrons. While other isotopes of hydrogen (deuterium and tritium) do contain neutrons, the most abundant and basic form of the hydrogen atom has no neutron.

2. If an atom contains one electron and one proton, will it carry as a whole is neutral

Yes, the atom will be electrically neutral.

Here is the simple reasoning:

- A proton carries a positive electrical charge (+1).

- An electron carries a negative electrical charge (-1).

- When one proton and one electron are together, their charges cancel each other out perfectly (+1 + (-1) = 0).

Question 11.

Thomson’s model of an atom explains how an atom as a whole is neutral.

Ans:

J.J. Thomson’s model of the atom, often called the “plum pudding” model, directly addressed the fundamental question of how an atom maintains electrical neutrality. He proposed that an atom is not a hard, indivisible sphere but a much more fluid structure. In this conception, the atom is envisioned as a uniform, positively charged sphere, akin to a pudding. Embedded within this sphere are the tiny, negatively charged electrons, which were thought to be scattered throughout, much like plums or raisins in the dessert. The key to the atom’s overall neutral charge lies in the precise balance between these components. The total negative charge of all the embedded electrons exactly cancels out the total positive charge of the sphere they are suspended in. Therefore, the atom possesses equal amounts of positive and negative electricity, resulting in no net charge and explaining its neutral state as a whole.

Question 12.

1. Which sub-atomic particle was discovered by Thomson?

2. Which sub-atomic particle was discovered by Goldstein.

3. Which sub-atomic particle was discovered by Chadwick.

Ans:

- The sub-atomic particle discovered by J.J. Thomson is the electron.

- The sub-atomic particle discovered by Eugen Goldstein is the proton.

- The sub-atomic particle discovered by James Chadwick is the neutron.

Question 13.

1. Name the sub-atomic particle whose charge is +1.

2. Name the sub-atomic particle whose charge is -1.

3. Name the sub-atomic particle whose charge is 0.

Ans:

- The sub-atomic particle with a charge of +1 is the proton.

- The sub-atomic particle with a charge of -1 is the electron.

- The sub-atomic particle with a charge of 0 is the neutron.

Question 14.

1. Which metal did rutherford select for his 𝛼 particle scattering experiment and why? 2. What do you think would be the observation of 𝛼 particle scattering experiment if carried out on (i) heavy nucleus like platinum (ii) light nuclei like lithium.

Ans:

1. Which metal did Rutherford select for his α-particle scattering experiment and why?

For his landmark alpha particle scattering experiment, Rutherford and his team chose a thin foil of gold. The selection was not arbitrary but based on a critical scientific requirement. Gold possesses an exceptional property: it is highly malleable. This allowed the physicists to hammer it into an extremely thin sheet or foil. This thinness was crucial because they needed a target that was only a few atoms thick. A thicker foil would have caused the alpha particles to scatter multiple times or get absorbed entirely, making the final deflection pattern impossible to interpret. The single, occasional large-angle deflections observed through the gold foil were only possible because most particles passed through the vast empty space of the atoms without any interaction, with only a few coming close to the tiny, dense nucleus.

2. Observations if the experiment was carried out on (i) a heavy nucleus like platinum and (ii) light nuclei like lithium.

(i) If the experiment were conducted using a foil of a heavy nucleus like platinum, the core observations would be quite similar to those with gold, as both are high-atomic-mass elements. The central nucleus in platinum is large and carries a very high positive charge due to its many protons. This strong positive charge would create an immensely powerful repulsive force against the positively charged alpha particles. Consequently, we would still observe a significant number of large-angle deflections, and perhaps even a slightly higher proportion of alpha particles bouncing straight back towards the source compared to gold. The fundamental conclusion about a dense, positively charged nucleus would remain unchanged and might even be more pronounced.

(ii) In contrast, using a foil of light nuclei like lithium would yield dramatically different and far less revolutionary results. A lithium atom has a very small nucleus with only 3 protons, resulting in a much weaker positive charge. The repulsive force it exerts on the incoming alpha particles would be feeble. Therefore, the vast majority of alpha particles would pass straight through the foil with little to no deflection. There would be virtually no large-angle scattering, and certainly no particles would be reversed in their path. An observer might mistakenly conclude that the atom was a uniform, “soft” entity with no hard core, completely missing the evidence for a concentrated nucleus that the gold foil experiment so brilliantly revealed.

Question 15.

On the basis of Rutherford’s model of an atom, which subatomic particle is present in the nucleus of an atom?

Ans:

Based on Ernest Rutherford’s groundbreaking atomic model, proposed in 1911 following his famous gold foil experiment, the subatomic particle identified within the nucleus of an atom is the proton.

Rutherford’s model was a revolutionary departure from earlier concepts. His experiment involved firing a beam of positively charged alpha particles at a very thin sheet of gold foil. The expectation was that these particles would pass straight through with minimal deflection. However, while most did, a surprising number were deflected at large angles, and a very few even bounced directly back.

This startling evidence led Rutherford to conclude that the atom must be mostly empty space, with its positive charge and most of its mass concentrated in an incredibly small, dense, central core which he termed the nucleus. He deduced that this central nucleus must contain positively charged particles to account for the repulsion of the alpha particles. He named these fundamental positive particles protons.

Question 16.

Which part of the atom was discovered by Rutherford?

Ans:

Prior to Ernest Rutherford’s groundbreaking work, the scientific community largely pictured the atom as a uniform, positively charged sphere, akin to a featureless lump of dough. To probe this idea, Rutherford and his team devised an experiment where they directed a stream of alpha particles—small, positively charged bits of matter—at an incredibly thin piece of gold foil. Based on the prevailing model, they anticipated that these particles would slice directly through the foil with little to no resistance, much like bullets passing through smoke.

The results, however, were stunningly contrary to this prediction. Although a majority of the alpha particles did indeed travel straight through the foil as expected, a curious and significant few behaved erratically. Some were deflected at sharp angles, while a rare number veered dramatically and rebounded directly back toward the source. This unexpected bounce-back was the crucial clue. Rutherford reasoned that such a powerful deflection could only occur if the atom contained a minuscule, incredibly dense, and positively charged center, which he termed the nucleus. This discovery shattered the earlier model, revealing that the atom is predominantly empty space dominated by a massive, concentrated core.

Question 17.

How was it shown that an atom has empty space?

Ans:

The idea that an atom is mostly empty space was dramatically demonstrated by a famous experiment conducted by Ernest Rutherford and his team in the early 1900s, known as the Gold Foil Experiment.

Before this experiment, the prevailing model was the “plum pudding” model, which suggested the atom was a uniform, positive sphere with negative electrons embedded within it. Rutherford tested this by firing a beam of positively charged alpha particles at an incredibly thin sheet of gold foil. If the plum pudding model were correct, these dense, fast-moving particles should have passed straight through with only minor deflections. However, the results were astonishing. While most alpha particles did indeed pass straight through as expected, a very small number were deflected at large angles, and some even bounced directly back towards the source.

Rutherford famously said it was “as if you fired a 15-inch naval shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.” This surprising outcome forced a radical new conclusion. The fact that most particles passed through unimpeded meant that the atom was not a solid sphere but was composed predominantly of empty space. The occasional large-angle deflections could only be explained if the atom’s positive charge and most of its mass were concentrated in an incredibly tiny, dense core—later named the nucleus. The empty space was where the tiny electrons orbited this nucleus, much like planets around a sun, making the atom overwhelmingly vacant.

Question 18.

State one major drawback of Rutherford’s model.

Ans:

A major shortcoming in Rutherford’s model of the atom was its failure to account for why atoms are stable. The prevailing understanding of physics at the time dictated that an electron orbiting a nucleus would, by virtue of its curved path, be constantly accelerating. Any accelerating charged particle must, according to this view, radiate energy away. This continuous energy loss would inevitably cause the electron’s orbit to decay, pulling it into a fatal spiral toward the nucleus. If this were accurate, every atom in the universe would almost instantaneously self-destruct, a scenario that is completely at odds with the permanent and stable nature of the matter we encounter.

Question 19.

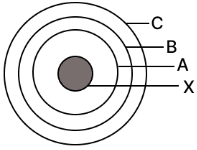

In the figure given alongside

(a) Name the shells denoted by A,B, and C. Which shell has least energy

(b) Name X and state the charge on it

(c) The above sketch is of …………. Model of an atom

Ans:

(a)

- The shells are generally named the K, L, and M shells (starting from the innermost).

- Shell A (the innermost one) has the least energy.

(b)

- X is the Nucleus.

- It has a positive charge.

(c)

- The above sketch is of Bohr’s Model of an atom.

Question 20.

Give the postulates of Bohr’s atomic model

Ans:

The Fundamental Postulates of Niels Bohr’s Atomic Model

Niels Bohr proposed his model of the atom in 1913 to overcome the limitations of earlier models, particularly by explaining why electrons do not spiral into the nucleus. His theory blended classical physics with the new ideas of quantum theory. The model is built upon several key postulates:

1. The Postulate of Stationary Orbits

Bohr proposed that electrons revolve around the nucleus only in specific, allowed circular paths, which he called stationary orbits or shells. Contrary to classical electromagnetic theory, an electron in one of these orbits does not radiate energy, despite undergoing acceleration. This prevents the electron from losing energy and falling into the nucleus, thus ensuring the atom’s stability.

2. The Postulate of Quantized Angular Momentum

Bohr specified a physical rule to determine which orbits are “allowed.” He stated that the angular momentum of an electron in a stationary orbit is quantized, meaning it can only take on certain discrete values. It is an integer multiple of the reduced Planck’s constant (ħ = h/2π). The mathematical condition is:

mvr = nħ = n(h/2π)

Where:

- *m* is the electron’s mass

- *v* is its orbital velocity

- *r* is the radius of the orbit

- *n* is the quantum number (n = 1, 2, 3, …), defining the orbit number.

- *h* is Planck’s constant

This rule effectively selects only certain orbits where the electron’s wave nature constructively interferes.

3. The Postulate of Energy Quantization and Photon Emission/Absorption

This postulate deals with how an electron gains or loses energy. While an electron remains in a stationary orbit, its energy is constant. However, an electron can transition from one allowed orbit (with energy Eᵢ) to another (with energy E_f).

- Emission of Light: When an electron “jumps” from a higher-energy orbit to a lower-energy one, it must lose energy. This energy is emitted in the form of a single photon (a quantum of light). The photon’s energy is exactly equal to the difference in energy between the two orbits.

E_photon = Eᵢ – E_f = hν

Where ν is the frequency of the emitted light. - Absorption of Light: Conversely, for an electron to jump from a lower-energy orbit to a higher-energy one, it must gain energy. This is achieved by absorbing a photon whose energy is precisely equal to the energy difference between the two orbits.

This postulate directly explains the existence of atomic emission and absorption spectra, as each spectral line corresponds to a specific electronic transition between quantized energy levels.

Exercise 4 (B)

Question 1.

1. Name the three fundamental particles of an atom.

2. Give the symbol and charge of each particle.

Ans:

1.

2.

| Particle | Symbol | Relative Charge | Location in Atom |

| Proton | p+ | +1 (Positive) | In the nucleus |

| Neutron | n0 | 0 (Neutral) | In the nucleus |

| Electron | e− | −1 (Negative) | Orbits the nucleus in shells |

Question 2.

Complete the table given below by identifying P, Q, R and S.

| Element | Symbol | No. of Protons | No. of neutrons | No. of Electrons |

| Sodium | 2311NA | 11 | P | 11 |

| Chlorine | 3517CI | Q | 18 | 17 |

| Uranium | R | 92 | 146 | 92 |

| S | 199F | 9 | 10 | 9 |

Ans:

The table can be completed by applying the fundamental rules of atomic structure:

- Atomic Number (Z): The number of protons and the number of electrons (in a neutral atom). It is equal to the number directly below the element’s symbol (often omitted, but implied by the number of protons/electrons).

- Mass Number (A): The total number of protons plus neutrons. It is the number directly above the element’s symbol.

- No. of Neutrons: A – Z.

Here is the completed table with the identified values P,Q, R, and S.

| Element | Symbol | Mass Number (A) | No. of Protons (Z) | No. of Neutrons | No. of Electrons |

| Sodium | Na | 23 | 11 | 12 (P) | 11 |

| Chlorine | Cl | 35 | 17 (Q) | 18 | 17 |

| Uranium | U | 238 (R) | 92 | 146 | 92 |

| Fluorine | F | 19 | 9 | 10 | 9 (S) |

Calculations:

- P (Sodium Neutrons): Mass Number – Protons = 23 – 11 = 12

- Q (Chlorine Protons): Equal to the number of electrons (in a neutral atom) = 17

- R (Uranium Mass No.): Protons + Neutrons = 92 + 146 = 238

- S (Fluorine Electrons): Equal to the number of protons (in a neutral atom) = 9

Question 3.

The atom of an element is made up of 4 protons, 5 neutrons and 4 electrons. What are its atomic number and mass number?

Ans:

The identity of any element is fundamentally anchored to a single, unchangeable feature: the count of protons within its nucleus. In this specific case, the nucleus contains four protons, which firmly establishes its atomic number as 4.

While the proton count defines the element, the total mass of the atom is influenced by both protons and neutrons, which are collectively called nucleons. The mass number is simply the sum of these two particles. Here, with 4 protons and 5 neutrons present, the mass number is calculated as 9.

To summarize the core identity of this atom:

- Atomic Number: 4

- Mass Number: 9

An atom with an atomic number of 4 is, by definition, the element Beryllium. This particular atom, with a mass number of 9, is a specific version of Beryllium known as the stable isotope Beryllium-9.

Question 4.

The atomic number and mass number of sodium are 11 and 23 respectively. What information is conveyed by this statement?

Ans:

This statement provides the fundamental identity card for a sodium atom, telling us exactly what it’s made of.

The atomic number of 11 conveys two critical pieces of information:

- It defines the element itself. Any atom that contains exactly 11 protons in its nucleus is, by definition, an atom of sodium. This number is its unique, unchangeable fingerprint.

- In a neutral atom, which has no overall electric charge, the number of negatively charged electrons orbiting the nucleus is also 11. This balance of 11 positive protons and 11 negative electrons is what makes the atom electrically neutral.

The mass number of 23 gives us the total count of heavy particles, or nucleons, located in the atom’s nucleus. This is the sum of its protons and neutrons. Since we know there are 11 protons, we can easily find the number of neutrons:

Number of Neutrons = Mass Number – Atomic Number = 23 – 11 = 12.

Therefore, this simple statement, “The atomic number and mass number of sodium are 11 and 23,” conveys a complete summary of the atom’s composition: A neutral sodium atom contains 11 protons, 11 electrons, and 12 neutrons in its structure.

Question 5.

Write down the names of the particles represented by the following symbols and explain the meaning of superscript and subscript numbers attached 1p1,0n1,−1e0

Ans:

The notation used for subatomic particles acts as a precise scientific label, instantly communicating their core characteristics. Each symbol is written with two key numbers: a superscript (the mass number) and a subscript (the atomic or charge number). Think of the mass number as an indicator of the particle’s heft, revealing the total count of protons and neutrons, which are the heavy constituents of the nucleus. The charge number, on the other hand, reveals the particle’s electrical property, showing its fundamental charge in relation to a proton.

Applying this code, the proton (¹H₁) is identified by a mass number of 1, confirming it as a substantial nucleon, and a charge number of +1, defining its positive identity. Its neutral partner, the neutron (¹₀n), shares the same mass number of 1, confirming its similar weight, but carries a charge number of 0, reflecting its lack of electrical charge. In stark contrast, the electron (⁰₋₁e) is defined by a mass number of 0, highlighting its incredibly light mass that is almost negligible compared to a nucleon, and a charge number of -1, which establishes its fundamental negative charge.

In essence, this symbolic language is a efficient shorthand. It allows us to immediately understand that a proton and neutron are the heavyweights of the atom, while the electron is a lightweight particle, with their respective charges being positive, neutral, and negative. This system provides a universal way to denote the identity of the building blocks of all matter.

Question 6.

From the symbol 24

12Mg

, state the mass number, the atomic number and electronic configuration of magnesium.

Ans:

When we look at the symbol ²⁴Mg₁₂, we’re looking at the identity card for a specific atom of magnesium. The two numbers tell us almost everything we need to know about its structure.

First, the bottom number, 12, is the atomic number. This is the element’s fundamental fingerprint. It tells us that the nucleus of this atom contains 12 positively charged protons. Because the number of protons defines an element, we know for certain this is magnesium.

The top number, 24, is the mass number. This isn’t the atom’s weight on a scale, but rather the total count of the heavy particles—protons and neutrons—in its nucleus. So, if there are 12 protons, simple subtraction (24 – 12 = 12) reveals that this particular magnesium atom also has 12 neutrons.

Now, for the electrons. In any neutral atom, the number of negatively charged electrons perfectly balances the positive charges in the nucleus. With 12 protons, a neutral atom of this magnesium isotope must also have 12 electrons orbiting the nucleus.

These 12 electrons aren’t randomly arranged; they fill specific energy levels or shells. The configuration for this atom is 2, 8, 2. This means the first and innermost shell holds 2 electrons, the second shell is filled with 8 electrons, and the third, outermost shell holds the remaining 2 electrons. This “2, 8, 2” arrangement is actually what gives magnesium its characteristic chemical properties, particularly its tendency to lose those two outer electrons when it reacts with other elements.

Question 7.

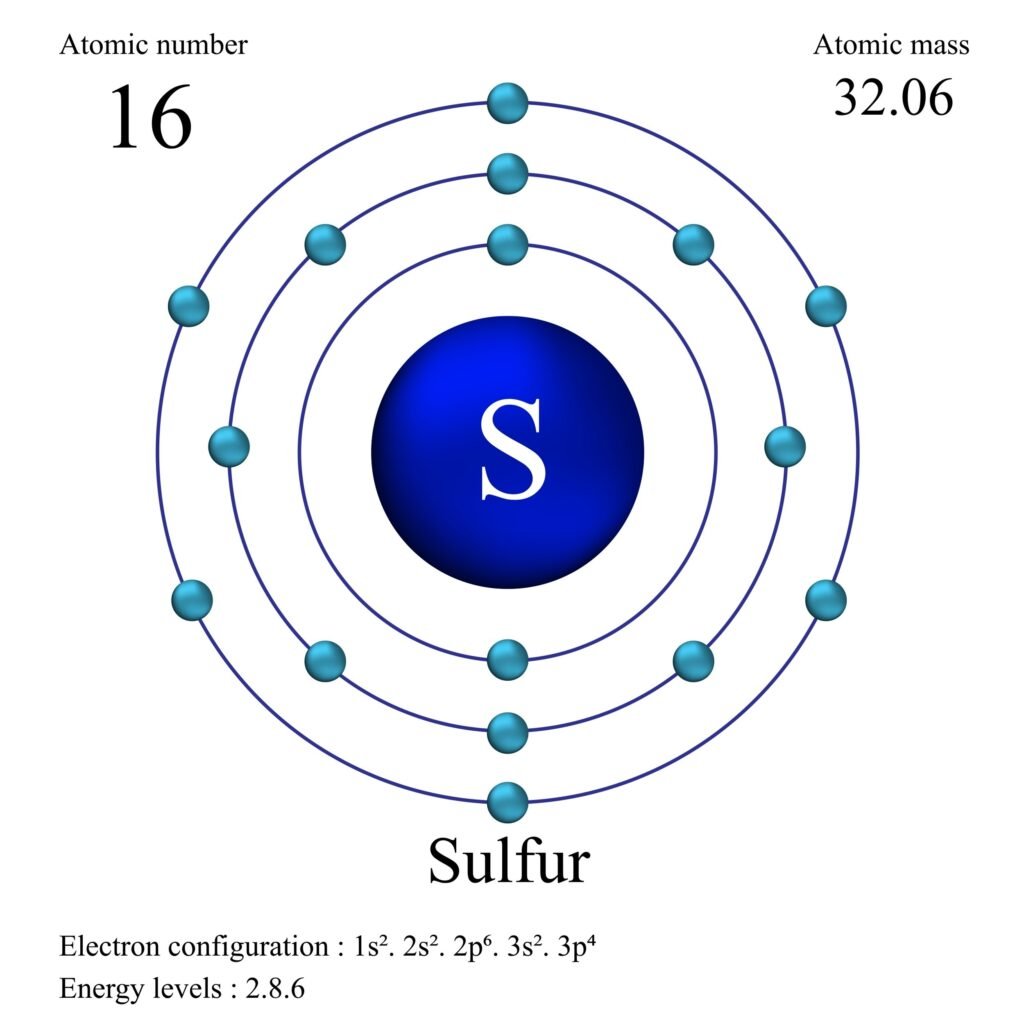

Sulphur has an atomic number 16 and a mass of 32. State the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of sulphur. Give a simple diagram to show the arrangement of electrons in an atom of sulphur.

Ans:

Protons and Neutrons in Sulfur

- Number of Protons: The atomic number (Z) of Sulfur is 16. In a neutral atom, the number of protons equals the atomic number.

- Protons = 16

- Number of Neutrons: The mass number (A) is 32. The number of neutrons is found by subtracting the atomic number (protons) from the mass number.

- Neutrons = Mass Number (A) – Atomic Number (Z)

- Neutrons = 32 – 16 = \mathbf16

Electron Arrangement (Bohr Model)

A neutral Sulfur atom has 16 electrons. These electrons are arranged in shells according to the 2n^2 rule (up to n=3 for the first 18 elements):

- K Shell (n=1): 2 electrons

- L Shell (n=2): 8 electrons

- M Shell (n=3): 6 electrons (Valence Shell)

The electron configuration is 2, 8, 6.

Here is a simple diagram showing the arrangement of electrons:

Question 8.

Explain the rule according to which electrons are filled in various energy levels.

Ans:

The arrangement of electrons in an atom’s different energy levels, or shells, doesn’t happen randomly but follows a specific sequence governed by three key rules. The first is the Aufbau Principle, which is a German word meaning “building up.” This principle states that electrons occupy the lowest available energy orbitals first before moving to higher ones. Think of it like filling a glass with water from the bottom up; you must fill the lower levels before any water can settle at the top. This means the 1s orbital is filled first, followed by 2s, then 2p, 3s, and so on, following a standard order often remembered using a specific diagonal diagram.

The second rule is the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which deals with how electrons share an orbital. It states that a maximum of two electrons can occupy a single atomic orbital, and they must have opposite spins. Imagine a single parking space that can only hold two cars, but one must be facing forward and the other backward. This opposite spin is a fundamental property that prevents the two electrons from being identical, allowing them to coexist peacefully in the same region of space without violating quantum rules.

Finally, for orbitals of equal energy, such as the three p orbitals or five d orbitals, Hund’s Rule of Maximum Multiplicity applies. This rule states that electrons will fill degenerate orbitals (orbitals of the same energy) singly first, and all these single electrons will have the same spin direction. Only after each orbital in the sub-level has one electron will pairing begin. It’s like people entering a bus; they will tend to occupy empty seats alone first, rather than immediately sitting next to a stranger. This arrangement minimizes the repulsion between the negatively charged electrons, making the atom more stable. Together, these three rules provide a clear and logical roadmap for determining the electron configuration of any element.

Question 9.

Draw the orbital diagram of 40 20Ca2+ ion and state the number of three fundamental particles present in it.

Ans:

Orbital Diagram for Ca²⁺ Ion

First, let’s determine the electron configuration.

- The element is Calcium (Ca).The electron configuration for a neutral calcium atom (²⁰Ca) is:

1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² - The ion given is Ca²⁺. The 2+ charge indicates the atom has lost two electrons.

- Therefore, the electron configuration for Ca²⁺ is:

1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶

Now, we can draw the orbital diagram following Hund’s Rule, which states that electrons will fill degenerate orbitals (orbitals of the same energy, like the three p orbitals) singly before pairing up.

The orbital diagram for Ca²⁺ is drawn below using spaces and lines for clarity:

text

1s: [↑↓]

2s: [↑↓]

2p: [↑↓] [↑↓] [↑↓]

3s: [↑↓]

3p: [↑↓] [↑↓] [↑↓]

4s: [ ] [ ] (Empty)

Explanation of the Diagram:

- Each box [ ] represents one atomic orbital.

- ↑ and ↓ represent electrons with opposite spins.

- The 1s, 2s, and 3s orbitals can hold a maximum of 2 electrons each, shown as paired arrows.

- The 2p and 3p subshells have three orbitals each. All six orbitals are fully filled with paired electrons.

- The 4s orbital is completely empty because the two valence electrons have been removed to form the 2+ cation.

Number of Three Fundamental Particles

The given ion is 2040Ca2+.

- Number of Protons: The atomic number (the subscript) is 20. The number of protons defines the element.

- Protons = 20

- Number of Neutrons: The mass number (the superscript) is 40. The mass number is the sum of protons and neutrons.

- Neutrons = Mass Number – Atomic Number

- Neutrons = 40 – 20 = 20

- Number of Electrons: For a neutral atom, electrons would equal protons (20). However, the 2+ charge means the atom has lost 2 electrons.

- Electrons = Atomic Number – Ionic Charge

- Electrons = 20 – (+2) = 18

- Electrons = 18

Question 10.

1. Write down the electronic configuration of the following:

(a) 27

13Y

(b) 35

17Y

2. Write down the number of electrons in X and neutrons in Y.

Ans:

1. Write down the electronic configuration of the following:

(a) For the element with symbol Y and atomic number 13:

The atomic number is 13, which means the atom contains 13 protons and, when neutral, 13 electrons. The electronic configuration is determined by filling the electron shells in order (K, L, M, etc.) up to a maximum of 2, 8, 18… electrons respectively.

- The K shell can hold 2 electrons.

- The L shell can hold 8 electrons.

- The remaining 3 electrons (13 – 2 – 8 = 3) go into the M shell.

Therefore, the electronic configuration is K=2, L=8, M=3.

(b) For the element with symbol Y and atomic number 17:

The atomic number is 17, indicating 17 protons and 17 electrons in a neutral atom.

- The K shell holds 2 electrons.

- The L shell holds 8 electrons.

- The remaining 7 electrons (17 – 2 – 8 = 7) go into the M shell.

Therefore, the electronic configuration is K=2, L=8, M=7.

2. Write down the number of electrons in X and neutrons in Y.

This question refers to the standard notation where an element is written as Mass NumberSymbolAtomic Number.

- For X: The notation is 27 13Y. The atomic number (13) gives the number of protons. In a neutral atom, the number of electrons is equal to the number of protons.

- Therefore, the number of electrons in X is 13.

- For Y: The notation is 35 17Y. The number of neutrons is calculated by subtracting the atomic number from the mass number.

- Number of neutrons = Mass Number – Atomic Number = 35 – 17.

- Therefore, the number of neutrons in Y is 18.

Exercise 4 (C)

Question 1.

How does the Modern atomic theory contradict and correlate with Dalton’s atomic theory?

Ans:

While Dalton’s atomic theory provided the foundational blueprint for chemistry, the modern atomic theory has significantly revised it based on new discoveries. The key contradiction lies in the idea of the atom itself. Dalton proposed atoms as the ultimate, indivisible particles, a concept definitively overturned by the discovery of subatomic particles like electrons, protons, and neutrons. Furthermore, his theory stated all atoms of an element are identical, which we now know is false due to the existence of isotopes—atoms of the same element with different numbers of neutrons and hence different masses. Finally, Dalton believed atoms simply combined in simple whole-number ratios, but modern science shows compound formation is governed by electron configuration and can involve complex ratios.

Despite these revisions, the core principles of Dalton’s theory brilliantly correlate with and form the bedrock of modern understanding. His central idea that matter is composed of tiny, distinct particles called atoms remains fundamentally true. The concept that atoms of different elements have different properties and masses is still a cornerstone, with atomic number (proton count) now being the defining property. Lastly, his law of conservation of mass during chemical reactions, which he explained through the rearrangement of indestructible atoms, remains a vital principle, even with our knowledge of energy-mass equivalence. Thus, the modern theory is not a rejection but a sophisticated evolution, building upon Dalton’s revolutionary insights.

Question 2.

1.What are inert elements?

2. Why do they exist as monoatoms in molecules?

3. What are valence electrons?

Ans:

1. What are inert elements?

Inert elements, more formally known as the Noble Gases, are a unique set of elements known for their remarkable lack of chemical reactivity. This group, located in the far-right column (Group 18) of the periodic table, includes elements like helium, neon, and argon. The secret to their inert nature lies in their atomic structure: they possess a complete and stable outer electron shell. This stable configuration means they have virtually no tendency to undergo the chemical processes—like gaining, losing, or sharing electrons—that other elements do.

2. Why do they exist as monoatoms in molecules?

These elements naturally exist as single, unbound atoms (a state called monatomic) because they are inherently stable by themselves. Having a perfectly balanced outer electron shell, they achieve a state of low energy and high stability that other elements can only reach by forming chemical bonds. Since they are already “satisfied,” they feel no need to link up with other atoms to form diatomic molecules (like H₂) or more complex compounds. You will find them simply as individual atoms, whether in a gas or a sealed glass tube.

3. What are valence electrons?

They reside in the outermost shell or energy level and are the sole participants in the interactions between atoms, which we call chemical bonding. The number and arrangement of these valence electrons are the primary factors that dictate an element’s chemical personality—how it reacts, what kinds of bonds it forms, and its overall strive to reach a stable, low-energy state by filling its outer shell.

Question 3.

In what respects do the three isotopes of hydrogen differ? Give their structures.

Ans:

The three isotopes of hydrogen—Protium, Deuterium, and Tritium—differ primarily in the number of neutrons present in their atomic nuclei. While all three have one proton and one electron, which defines them as hydrogen, their neutron count varies. This difference in neutrons gives them distinct atomic masses and physical properties, such as density, while their chemical behavior remains very similar.

Their structures are as follows:

- Protium: It is the most common form, making up over 99.98% of natural hydrogen. Its nucleus is a single proton, with no neutrons.

- Structure: Nucleus = 1 proton; Orbiting = 1 electron.

- Deuterium: Often called “heavy hydrogen,” its nucleus contains one proton and one neutron. Water made with deuterium (D₂O) is known as “heavy water.”

- Structure: Nucleus = 1 proton + 1 neutron; Orbiting = 1 electron.

- Tritium: This is a radioactive isotope. Its nucleus consists of one proton and two neutrons. It is unstable and decays over time.

- Structure: Nucleus = 1 proton + 2 neutrons; Orbiting = 1 electron.

Question 4.

Match the atomic numbers 4, 14, 8, 15 and 19 with each of the following:

- A solid non-metal of valency 3.

- A gas of valency 2.

- A metal of valency 1.

- A non-metal of valency 4.

Ans:

- A solid non-metal of valency 3: Atomic Number 15

- Element: Phosphorus (P). It is a solid at room temperature and commonly forms compounds with a valency of 3 (e.g., in PCl₃).

- A gas of valency 2: Atomic Number 8

- Element: Oxygen (O). It is a diatomic gas (O₂) and has a valency of 2, as seen in compounds like H₂O and MgO.

- A metal of valency 1: Atomic Number 19

- Element: Potassium (K). It is an alkali metal and readily loses one electron to form ions with a +1 charge, giving it a valency of 1.

- A non-metal of valency 4: Atomic Number 14

- Element: Silicon (Si). While it is a metalloid, it is often classified as a non-metal in many contexts. Its most common valency is 4, as in its oxide SiO₂ and its chloride SiCl₄.

Question 5.

Draw diagrams representing the atomic structures of the following:

- Sodium atom

- Chlorine ion

- Carbon atom

- Oxygen ion

Ans:

Atomic Structures

1. Sodium Atom (Na)

- Atomic Number (Z): 11

- Protons: 11

- Electrons: 11 (neutral atom)

- Electron Configuration: 2, 8, 1 (1 electron in the outermost shell)

2. Chlorine Ion (Cl^-)

- Atomic Number (Z): 17

- Protons: 17

- Electrons: 18 (17 electrons in a neutral atom + 1 gained electron to form Cl^-)

- Electron Configuration: 2, 8, 8 (a stable octet, like Argon)

3. Carbon Atom (C)

- Atomic Number (Z): 6

- Protons: 6

- Electrons: 6 (neutral atom)

- Electron Configuration: 2, 4 (4 electrons in the outermost shell)

4. Oxygen Ion (O^2-)

- Atomic Number (Z): 8

- Protons: 8

- Electrons: 10 (8 electrons in a neutral atom + 2 gained electrons to form O^2-)

- Electron Configuration: 2, 8 (a stable octet, like Neon)

Question 6.

What is the significance of the number of protons found in the atoms of different elements?

Ans:

The number of protons in an atom’s nucleus, known as the atomic number, is the element’s fundamental identity card. It is this number alone that defines what element an atom is. For instance, every atom with exactly 6 protons is carbon, while every atom with 8 protons is oxygen; changing the proton count transforms it into a completely different element.

This atomic number doesn’t just name the element—it directly governs its chemical character. It determines the number of electrons a neutral atom has, and the arrangement of these electrons dictates how the element will interact and bond with others. This is why the Periodic Table is arranged by increasing proton number, as this sequence creates the repeating patterns of properties we observe.

Question 7.

Elements X, Y and Z have atomic numbers 6, 9 and 12 respectively. Which one:

- Forms an anion

- Forms a cation

- Has four electrons in its valence shell?

Ans:

Based on the atomic numbers:

- Element X (Atomic number 6): This is Carbon. It has an electron configuration of 2,4, meaning it has four electrons in its valence shell.

- Element Y (Atomic number 9): This is Fluorine. Its electron configuration is 2,7. It needs one more electron to complete its valence shell, so it readily gains an electron to form a negative ion (anion), specifically F⁻.

- Element Z (Atomic number 12): This is Magnesium. Its electron configuration is 2,8,2. It has two electrons in its outer shell that it can easily lose to achieve a stable configuration, forming a positive ion (cation), specifically Mg²⁺.

In summary:

- Forms an anion: Element Y (Fluorine)

- Forms a cation: Element Z (Magnesium)

- Has four electrons in its valence shell: Element X (Carbon)

Question 8.

Element X has electronic configurations 2, 8, 18, 8, 1. Without identifying X,

- Predict the sign and charge on a simple ion of X.

- Write if X will be an oxidizing agent or a reducing agent. Why?

Ans:

Based on the electronic configuration 2, 8, 18, 8, 1:

- Sign and Charge: The atom will form a positive ion with a charge of +1 (X⁺). This is because it has a single electron in its outermost valence shell, which it will readily lose to achieve a stable, full outer shell configuration.

- Oxidizing or Reducing Agent: Element X will be a reducing agent. By losing its one valence electron, it gets oxidized itself and causes the other species it reacts with to be reduced.

Question 9.

1. Define the term: Mass number

2. Define the term: Ion

3. Define the term: Cation

4. Define the term: Anion

5. Define the term: Element.

6. Define the term: orbit

Ans:

1. Mass Number

An atom’s mass number represents the combined total of protons and neutrons packed into its nucleus. As these two particles account for nearly all an atom’s weight, this figure provides a straightforward, whole-number value for its approximate mass.

2. Ion

This charge develops when there is an imbalance between the number of positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. An atom transforms into an ion through the loss or acquisition of electrons.

3. Cation

A cation is a positively charged ion. It originates when a neutral atom sheds one or more of its electrons. This loss leaves the atom with a surplus of protons compared to electrons, creating a net positive electrical charge.

4. Anion

It forms when a neutral atom attracts and holds additional electrons. This gain results in more electrons than protons, giving the particle an overall negative charge.

5. Element

An element is a pure, fundamental substance consisting of only one kind of atom. Every atom of a given element is defined by a unique number of protons in its nucleus, known as its atomic number. This proton count is the element’s fingerprint, dictating its identity and location on the periodic table.

6. Orbit

In historical atomic theory, an orbit was described as the specific, well-defined path—either circular or elliptical—that an electron traveled around the nucleus. This planetary model has since been refined and replaced by the modern concept of an “orbital,” which represents a three-dimensional zone where there is a high probability of locating an electron.

Question 10.

From the symbol 4 2He for the element helium, write down the mass number and the atomic number of the element.

Ans:

From the symbol ⁴₂He:

The mass number is 4.

The atomic number is 2.

Question 11.

Five atoms are labeled A to E

| Atoms | Mass No | Atomic No. |

| A | 40 | 20 |

| B | 19 | 9 |

| C | 7 | 3 |

| D | 16 | 8 |

| E | 14 | 7 |

(a) Which one of these atoms:

(i) contains 7 protons

(ii) has electronic configuration 2,7

(b) Write down the formula in the compound formed between C and D

(c) Predict : (i) metals (ii) non-metals

Ans:

Here is the analysis of the five atoms based on the provided data:

(a) Identifying Atoms

To answer this, we primarily use the Atomic Number (Z), which equals the number of protons and electrons in a neutral atom.

| Atom | Mass No. (A) | Atomic No. (Z) | Protons (Z) | Electrons (Z) | Electronic Configuration | Element |

| A | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 2, 8, 8, 2 | Calcium (Ca) |

| B | 19 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2, 7 | Fluorine (F) |

| C | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2, 1 | Lithium (Li) |

| D | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2, 6 | Oxygen (O) |

| E | 14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 2, 5 | Nitrogen (N) |

(i) contains 7 protons:

- Atom E (Atomic Number 7, Nitrogen)

(ii) has electronic configuration 2, 7:

- Atom B (Atomic Number 9, Fluorine)

(b) Formula of the Compound Formed Between C and D

| Atom | Element | Valency | Ion Formed |

| C | Lithium (Li) | 1 (loses 1 electron) | Li+ |

| D | Oxygen (O) | 2 (gains 2 electrons) | O2− |

Using the criss-cross method, the valency of 1 from C goes to D, and the valency of 2 from D goes to C.

- Formula: C2D(orLi2O, Lithium Oxide)

(c) Predict Metals and Non-metals

An element is generally classified as a metal if it has 1, 2, or 3 electrons in its outermost shell (it tends to lose electrons). It is a non-metal if it has 4, 5, 6, or 7 electrons in its outermost shell (it tends to gain or share electrons).

(i) Metals:

- A (Configuration: 2, 8, 8, 2)

- C (Configuration: 2, 1)

- Metals: A and C

(ii) Non-metals:

- B (Configuration: 2, 7)

- D (Configuration: 2, 6)

- E (Configuration: 2, 5)

- Non-metals: B, D, and E

Question 12.

An atom of an element has two electrons in the M shell. What is the (a) atomic number (b) number of protons in this element?

Ans:

Think of the electron shells as a set of concentric rings or orbits. The innermost ring is called the K-shell, the next one out is the L-shell, and the one after that is the M-shell. These aren’t just labels; they correspond to specific energy levels. The K-shell can only ever hold 2 electrons. Once it’s full, new electrons start filling the L-shell, which has a capacity for 8 electrons. After the L-shell is completely filled, electrons begin to populate the M-shell.

The puzzle states that this particular atom has two electrons in its M shell. This is a crucial clue. It means the inner shells before it are completely filled. If the M-shell has any electrons at all, we know for a fact that the K and L shells must be full. Therefore, the electron breakdown is:

- K-shell: Full with 2 electrons.

- L-shell: Full with 8 electrons.

- M-shell: Contains 2 electrons.

Adding these up gives us the total number of electrons in the atom: 2 + 8 + 2 = 12 electrons.

Now, for a neutral atom that isn’t an ion, the number of negatively charged electrons is perfectly balanced by the number of positively charged protons in the nucleus. Since our atom has 12 electrons, it must also contain 12 protons.

The atomic number of an element is fundamentally defined as the number of protons in its nucleus. An atom with 12 protons is, by definition, the element Magnesium.

So, to answer your questions directly:

(a) Atomic Number

The atomic number is 12.

(b) Number of Protons

The number of protons is 12.

This configuration, specifically the two electrons in its outermost M-shell, is what gives Magnesium its characteristic chemical properties, such as its tendency to lose those two electrons and form a +2 ion.

Question 13.

24

12Mg and

26

12Mg are symbols of isotopes of magnesium.

(a) Compare the atoms of these isotopes with respect to :

i. the composition of their nuclei

ii. their electronic configurations

(b) Give reasons why the two isotopes of magnesium have different mass numbers.

Ans:

(a) Comparison of the Atoms of ²⁴Mg and ²⁶Mg

i. The composition of their nuclei

The fundamental difference between these isotopes lies in the composition of their nuclei.

- For ²⁴₁₂Mg (Magnesium-24): The nucleus contains 12 protons and 12 neutrons.

- For ²⁶₁₂Mg (Magnesium-26): The nucleus contains 12 protons and 14 neutrons.

Both nuclei have an identical number of protons, but Magnesium-26 has two more neutrons in its nucleus than Magnesium-24.

ii. Their electronic configurations

The electronic configurations of both isotopes are identical.

A neutral atom has the same number of electrons as it has protons. Since both isotopes have 12 protons, they also both have 12 electrons. These 12 electrons will occupy the same atomic orbitals in the same way.

The electron configuration for both ²⁴₁₂Mg and ²⁶₁₂Mg is:

1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s²

(b) Reasons for the different mass numbers

The mass number of an atom is the sum of the number of protons and neutrons in its nucleus (A = Z + N).

- The two isotopes have the same number of protons (12). This identical proton number is what defines them both as atoms of the element magnesium.

- However, they have a different number of neutrons in their nuclei (12 in Mg-24 vs. 14 in Mg-26).

Since the mass number is the total of protons and neutrons, and the neutron count is different while the proton count is the same, the two isotopes necessarily have different mass numbers (24 and 26).

Question 14.

What are nucleons? How many nucleons are present in phosphorus? Draw its structure.

Ans:

What are Nucleons?

Nucleons are the particles found in the nucleus of an atom. There are two types: protons (positively charged) and neutrons (neutral).

Nucleons in Phosphorus

A standard atom of phosphorus has 31 nucleons.

- Atomic Number of Phosphorus: 15 (This is the number of protons).

- Mass Number: 31 (This is the total number of protons + neutrons).

- Therefore, it has 15 protons and 16 neutrons.

Structure of a Phosphorus Atom

The structure shows 15 protons and 16 neutrons clustered in the nucleus. The 15 electrons are arranged in three energy levels (shells) around it.

text

Electrons

/ • • \

/ • • \

| • N • | <- “N” represents the nucleus

| • • | containing 15 protons & 16 neutrons.

\ • • • • /

\___________/

Key:

• = Electron

- First Shell (K): 2 electrons

- Second Shell (L): 8 electrons

- Third Shell (M): 5 electrons

Question 15.

What are isotopes? With reference to which fundamental particle do isotopes differ? Give two uses of isotopes.

Ans:

Isotopes are distinct variants of a single element, characterized by their identical chemical behavior but differing atomic masses. This occurs because while they possess the same number of protons, defining the element’s identity, the number of neutrons within their nuclei varies. Therefore, the atomic number remains constant across isotopes of an element, but their mass number changes due to this neutron count difference.

The unique properties of specific radioactive isotopes, or radioisotopes, make them incredibly valuable across various fields. In medicine, the controlled application of radiation from isotopes like Cobalt-60 is a cornerstone of cancer therapy, where it is used to target and shrink malignant tumors. Another critical application is in archaeology and geology, where the predictable decay of the Carbon-14 isotope serves as a reliable clock. By measuring the remaining Carbon-14 in an ancient object, scientists can accurately estimate its age, a process known as radiocarbon dating.

Question 16.

Why do 35 17CI and 37 17CI have the same chemical properties? In what respect do these atoms differ?

Ans:

The atoms 1735Cl and 1737Cl have the same chemical properties because chemical behavior is governed primarily by the number and arrangement of electrons in an atom. Since both isotopes of chlorine contain the same number of protons (17) in their nucleus, they also possess an identical number of electrons (17) when electrically neutral. This identical electron configuration, specifically the same number of electrons in the outermost shell (seven valence electrons), dictates how they interact with other atoms. Therefore, both isotopes will form bonds in the same way, such as by gaining one electron to achieve a stable octet, leading to the formation of similar compounds like NaCl or HCl.

The respect in which these atoms differ is in their nuclear structure. Although they have the same atomic number (17), they have different mass numbers (35 and 37). This difference in mass arises because 1735Cl contains 18 neutrons in its nucleus (35 – 17 = 18), while 1737Cl contains 20 neutrons (37 – 17 = 20). These atoms are called isotopes—variants of the same element that differ in their number of neutrons and, consequently, their atomic mass. This difference in mass can lead to slight variations in their physical properties, such as density and rate of diffusion, but it does not affect their fundamental chemical identity.

Question 17.

Explain fractional atomic mass. What is the fractional mass of chlorine?

Ans:

Fractional Atomic Mass

Most elements have isotopes—atoms of the same element with different numbers of neutrons. The atomic mass listed on the periodic table is a weighted average of the masses of all naturally occurring isotopes, based on their abundance. Because this average isn’t a whole number, it’s often called a fractional atomic mass.

Fractional Mass of Chlorine

Chlorine has two main stable isotopes:

- Chlorine-35: Mass ~35 u, Abundance = 75.77%

- Chlorine-37: Mass ~37 u, Abundance = 24.23%

To find its average (fractional) atomic mass:

= (Mass of Cl-35 × Abundance) + (Mass of Cl-37 × Abundance)

= (35 × 0.7577) + (37 × 0.2423)

= 26.5195 + 8.9651

= 35.4846 u

On the periodic table, this is rounded to 35.5 u.

Question 18.

1. What is meant by the ‘atomic number of an element’?

2. Complete the table given below

| No. of protons | No. of electrons | No. of Neutrons | Atomic Number | Mass number | |

| 3517CI | |||||

| 3717CI |

3. Write down the electronic configuration of

(i) chlorine atom (ii) chlorine ion

Ans:

1. What is Meant by the ‘Atomic Number of an Element’?

The atomic number of an element, denoted by the letter Z, is the fundamental property that defines the identity of the element itself.

- It represents the number of protons found in the nucleus of a single atom of that element.

- In a neutral atom, the atomic number also equals the number of electrons surrounding the nucleus.

This number is unique for each element and determines its position in the Modern Periodic Table. For example, if an element has an atomic number of 8, every atom of that element contains exactly 8 protons and, in its neutral state, 8 electrons.

2. Complete the Table

The table below describes two isotopes of Chlorine (Cl).

| Symbol | No. of Protons (Z) | No. of Electrons | No. of Neutrons (A−Z) | Atomic Number (Z) | Mass Number (A) |

| 1735Cl | 17 | 17 | 18 (35 – 17) | 17 | 35 |

| 1737Cl | 17 | 17 | 20 (37 – 17) | 17 | 37 |

3. Write Down the Electronic Configuration

The electronic configuration describes the arrangement of electrons in the various shells (K, L, M, etc.). The maximum number of electrons in the n-th shell is given by 2n^2.

(i) Chlorine Atom (Cl)

A neutral chlorine atom has 17 electrons (Z=17).

- Configuration: 2, 8, 7 (K-shell: 2, L-shell: 8, M-shell: 7)

(ii) Chloride Ion (Cl^-)

A chloride ion is formed when a chlorine atom gains one electron to achieve a stable octet (full M-shell).

- Total Electrons: 17 + 1 = \mathbf 18 electrons.

- Configuration: 2, 8, 8 (K-shell: 2, L-shell: 8, M-shell: 8)

Question 19.

1. Name the following: The element which does not contain any neutron in its nucleus. 2.Name the following: An element having valency ‘zero’

3. Name the following: Metal with valency 2

4. Name the following: Two atoms having the same number of protons and electrons but different number of neutrons.

5. Name the following: The shell closest to the nucleus of an atom

Ans:

- Protium (an isotope of Hydrogen)

- Neon (or any Noble Gas like Helium, Argon)

- Magnesium (or any metal like Calcium, Zinc)

- Isotopes (e.g., Carbon-12 and Carbon-14)

- K-shell

Question 20.

1. Give a reason Physical properties of isotopes are different.

2. Give reason Argon does not react.

3. The Actual atomic mass is greater than mass number.

4. Give reason 35 17CI and 37 17CI do not differ in their chemical reactions.

Ans:

- Physical properties of isotopes are different because the difference in the number of neutrons changes their mass. This affects properties like density, rate of diffusion, and boiling/melting points, which depend on mass.

- Argon does not react because it has a stable, fully filled outermost electron shell (octet). This makes it energetically stable and unreactive.

- The actual atomic mass is greater than the mass number because the mass number is a simple count of protons and neutrons, while the actual mass includes the tiny binding energy that holds the nucleus together (mass defect).

- ³⁵Cl and ³⁷Cl do not differ in their chemical reactions because they have the same number of electrons and the same electron configuration, which solely determines an element’s chemical behavior.

Question 21.

An element A atomic number 7 mass numbers 14

B electronic configuration 2,8,8

C electrons 13, neutrons 14

D Protons 18 neutrons 22

E Electronic configuration 2,8,8,1

State Valency of each element

An element A atomic number 7 mass numbers 14

B electronic configuration 2,8,8

C electrons 13, neutrons 14

D Protons 18 neutrons 22

E Electronic configuration 2,8,8,1

State (i) Valency of each element (ii) which one is a metal (iii) which is non-metal (iv) which is an inert gas

Ans:

Based on the provided data, we can first identify each element and then determine its properties.

Identification of Elements:

- Element A: Atomic number 7 identifies it as Nitrogen (N). Its mass number is 14.

- Element B: The electronic configuration 2,8,8 shows a completely filled valence shell, which is the characteristic of a noble gas. This configuration is for Argon (Ar).

- Element C: The number of electrons in a neutral atom equals its atomic number. So, atomic number is 13, identifying it as Aluminium (Al). The number of neutrons is given as 14.

- Element D: The number of protons is the atomic number. So, atomic number is 18, identifying it as Argon (Ar). This is an isotope of the element found in B.

- Element E: The electronic configuration 2,8,8,1 shows a single electron in its outermost shell. This is the configuration of Potassium (K).

(i) Valency of each element

- A (Nitrogen): Its electronic configuration is 2,5. It needs 3 electrons to complete its octet. Hence, its valency is 3.

- B (Argon): Its electronic configuration is 2,8,8 (stable octet). It has no tendency to gain or lose electrons. Hence, its valency is 0.

- C (Aluminium): Its electronic configuration is 2,8,3. It can lose 3 electrons to achieve a stable configuration. Hence, its valency is 3.

- D (Argon): As with element B, its atomic number is 18, so it is an inert gas with a valency of 0.

- E (Potassium): Its electronic configuration is 2,8,8,1. It can easily lose 1 electron to achieve a stable configuration. Hence, its valency is 1.

(ii) Which one is a metal?

Elements that have 1, 2, or 3 electrons in their outermost shell are metals.

- C (Aluminium) with 3 valence electrons and E (Potassium) with 1 valence electron are metals.

(iii) Which is non-metal?

Elements that have 4 or more electrons in their outermost shell are typically non-metals.

- A (Nitrogen) with 5 valence electrons is a non-metal.

(iv) Which is an inert gas?

Inert gases, or noble gases, have a completely filled valence shell.

- B (Argon) and D (Argon) are both inert gases.

Question 22.

Question 1.

Choose the correct option

Rutherford’s alpha-particle scattering experiment discovered

- Electron

- Proton

- Atomic nucleus

- Neutron

Question 2.

Choose the correct option

The number of valence electrons in O2- is :

- 6

- 8

- 10

- 4

Question 3.

Choose the correct option

Which of the following is the correct electronic configuration of potassium?

- 2,8,9

- 8,2,9

- 2,8,8,1

- 1,2,8,8

Question 4.

Choose the correct option:

The mass number of an atom whose unipositive ion has 10 electrons and 12 neutrons is :

- 22

- 23

- 21

- 20

Question 23.

1. Explain

Octet rule for the formation of sodium chloride

2. Explain

Duplet rule for the formation of hydrogen

Ans:

1. Octet Rule and the Formation of Sodium Chloride

The Octet Rule states that atoms tend to combine in such a way that they each have eight electrons in their outermost shell, achieving a stable electron configuration similar to the noble gases. The formation of sodium chloride (NaCl) is a classic example of this rule in action through ionic bonding. A sodium (Na) atom has one electron in its outermost (third) shell, which it readily donates to achieve a stable, full inner shell configuration. By losing this single electron, sodium becomes a positively charged ion (Na⁺) with a complete octet in its second shell.

This donated electron is accepted by a chlorine (Cl) atom. Chlorine has seven electrons in its outermost shell and requires just one more to complete its octet. By gaining an electron, chlorine attains a stable eight-electron configuration and becomes a negatively charged chloride ion (Cl⁻). The powerful electrostatic attraction between the newly formed positive sodium ion and the negative chloride ion pulls them together, creating a strong ionic bond. This results in the crystalline compound we know as sodium chloride, where each ion is stably surrounded by ions of the opposite charge.

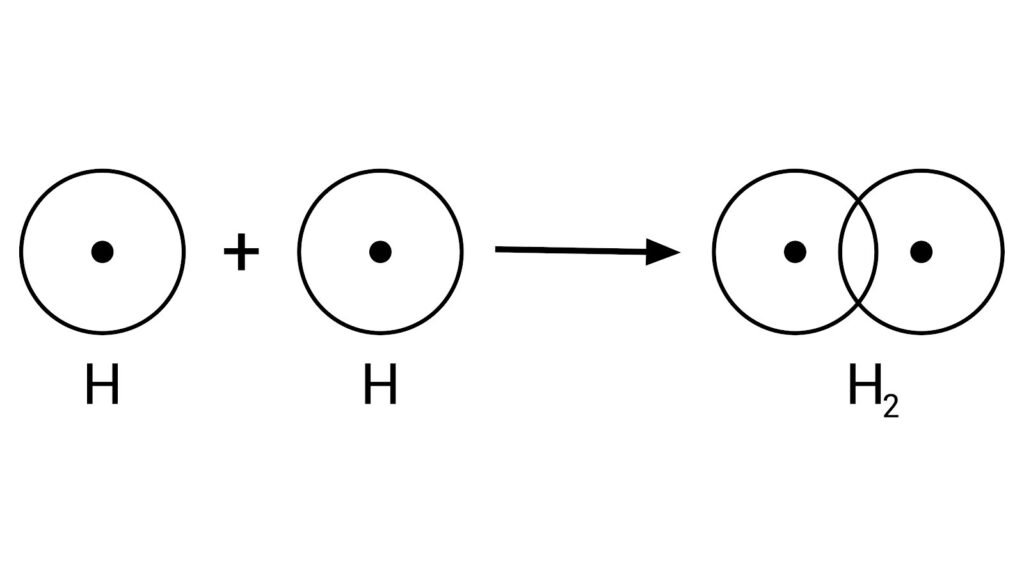

2. Duplet Rule and the Formation of a Hydrogen Molecule

The Duplet Rule is a specific case of stability where atoms, typically small ones, achieve a stable configuration by having two electrons in their first and only electron shell, mimicking the stable structure of helium. Hydrogen is the prime example of this rule. A single hydrogen atom has just one electron and is unstable. To achieve stability, two hydrogen atoms share their single electrons with each other.

When these two atoms come close, their individual electrons become attracted to the nucleus of both atoms simultaneously. This mutual sharing results in a pair of electrons—a single covalent bond—that is effectively orbiting both nuclei. This shared electron pair gives each hydrogen atom the stable configuration of two electrons in its outer shell, thus satisfying the duplet rule. The bond formed is a covalent bond, and the resulting molecule is a stable, neutral H₂ molecule, where the two atoms are linked together by this shared pair of electrons.

Question 24.

Complete the following table relating to the atomic structure of some elements.

| Element Symbol | AtomicNumber | MassNumber | Numbers of neutrons | Number of Electrons | Number of Protons |

| Li | 3 | 6 | |||

| CI | 17 | 20 | |||

| Na | 12 | 11 | |||

| AI | 27 | 13 | |||

| S | 32 | 16 |

Ans:

| Element Symbol | Atomic Number (Z) | Mass Number (A) | Number of Neutrons (A−Z) | Number of Electrons (Z) | Number of Protons (Z) |

| Li | 3 | 6 | 6−3=3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cl | 17 | 17+20=37 | 20 | 17 | 17 |

| Na | 11 | 11+12=23 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| Al | 13 | 27 | 27−13=14 | 13 | 13 |

| S | 16 | 32 | 32−16=16 | 16 | 16 |

Exercise 4 (D)

Question 1.

How do atoms attain noble gas configurations?

Ans:

1. Electron Transfer (Ionic Bonding)

- Atoms with 1-3 outer electrons (like Sodium) tend to lose them completely.

- Atoms with 5-7 outer electrons (like Chlorine) tend to gain electrons.

- This transfer forms positive and negative ions that attract each other, creating an ionic bond.

2. Electron Sharing (Covalent Bonding)

- Atoms that need to gain electrons (like two Oxygen atoms) can share pairs of electrons between them.

- Each shared pair counts toward the stable configuration of both atoms, forming a covalent bond and a molecule.

3. Electron Pooling (Metallic Bonding)

- In metals, atoms release their outer electrons into a shared “sea.”

- This pool of delocalized electrons holds the positive metal ions together, allowing each atom to exist in a stable, electron-deficient state.

Question 2.

Define electrovalent bond.

Ans:

An electrovalent bond, also commonly known as an ionic bond, is a fundamental type of chemical linkage formed by the complete transfer of one or more electrons from one atom to another. This process occurs between atoms that have a significant difference in their tendency to gain or lose electrons, typically between a metal and a non-metal. The metal atom, which has a low ionization energy, readily donates its valence electron(s) to achieve a stable electron configuration. Simultaneously, the non-metal atom, which has a high electron affinity, accepts those electron(s) to complete its own outer shell.

This electron transfer does not leave the atoms unchanged; instead, it transforms them into electrically charged particles called ions. For example, when a sodium atom donates an electron to a chlorine atom, it forms a sodium cation (Na⁺) and a chloride anion (Cl⁻). The resulting bond is not a physical entity but the powerful electrostatic force of attraction that holds these oppositely charged ions together in a stable, crystalline structure.

The compounds formed by electrovalent bonding, known as ionic compounds, exhibit distinct characteristics due to the strength of this electrostatic attraction. They are generally solid at room temperature, have high melting and boiling points, and are often soluble in water. Furthermore, in their molten or dissolved state, these compounds can conduct electricity, as the ions are free to move and carry an electric current. This property is a direct consequence of the charged particles created by the electron transfer that defines the electrovalent bond.

Question 3.

Elements are classified as metals, non-metal, metalloids, and inert gases. Which of them form an electrovalent bond?

Ans:

Electrovalent bonds are formed between metals and non-metals.

- Metals lose electrons to form positive ions (cations).

- Non-metals gain these electrons to form negative ions (anions).

- The resulting opposite charges attract, creating a strong electrovalent (ionic) bond.

Metalloids typically form covalent bonds, and inert gases are stable and generally do not form bonds.

Question 4.

1. An atom X has three electrons more than the noble gas configuration. What type of ion will it form?

2. Write the formula of its (X)

sulphate

nitrate

phosphate

carbonate

Hydroxide.

Ans: