1. What is Force?

Force is a push or pull that changes or tends to change the state of rest or of uniform motion of a body in a straight line. It can also change the shape and size of a body. The SI unit is the newton (N).

2. Turning Effect of Force (Moment)

When a force is applied to a pivoted object, it can cause rotation. This turning effect is called Moment of Force or Torque.

Formula: Moment of a force (τ) = Force (F) × Perpendicular distance from the pivot (d)

Principle of Moments: For a body in equilibrium, the sum of clockwise moments about a point is equal to the sum of anticlockwise moments about the same point.

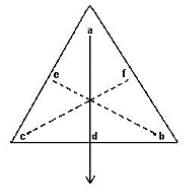

3. Centre of Gravity

The centre of gravity of a body is the point where the entire weight of the body is considered to act. For regularly shaped objects, it is at their geometric centre. Understanding its position is crucial for an object’s stability.

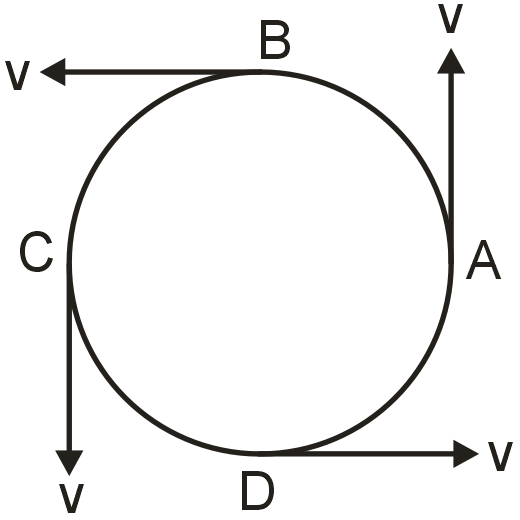

4. Uniform Circular Motion

When a body moves in a circular path with a constant speed, its velocity is continuously changing because the direction changes. This change in velocity means the body is accelerating.

Centripetal Force: This is the force that acts towards the centre of the circular path and keeps the body moving in a circle. For example, the gravitational force of the sun provides the centripetal force for the Earth’s revolution.

5. Newton’s Laws of Motion

First Law (Law of Inertia): A body continues in its state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external unbalanced force.

Second Law: The rate of change of momentum of a body is directly proportional to the applied force and takes place in the direction of the force. (F = m × a).

Third Law: These forces act on two different bodies.

6. Friction

Friction is a force that opposes the relative motion between two surfaces in contact. It has both advantages (like walking, braking) and disadvantages (like wear and tear of machines).

EXERCISE- 1 (A)

Question 1: What are contact forces? Give two Examples.

Ans: Contact forces happen when objects physically touch each other.

Two examples are:

Frictional Force: This is the resistance that slows down a sliding object, like a box being pushed on the floor.

Muscular Force: This is the force created by living muscles, such as when a person lifts a weight or throws a ball.

Question 2: What are non – contact forces? Give two example.

Ans: Non–contact forces are forces that can act on an object without any physical contact. They act through a distance.

Two examples are:

Magnetic force – Example: A magnet pulling an iron nail without touching it.

Gravitational force – Example: The Earth pulling the Moon towards itself, keeping it in orbit.

Question 3: Classify the following amongst contact and non-contact forces. (a) Frictional force (b) normal reaction force, (c) force of tension in a string (d) gravitation force (e) electrostatic force (f) magnetic force

Ans: Forces can be categorized into two main types based on whether physical contact is required for their operation.

1. Contact Forces: These are the forces that occur when two interacting objects are in direct physical contact with each other.

(a) Frictional force: This force opposes the relative motion between two surfaces that are in contact. For example, the friction between your shoe and the ground allows you to walk.

(b) Normal reaction force: This is the support force exerted by a stable surface on an object in contact with it, acting perpendicular to the surface. For instance, a table exerts a normal force upwards on a book placed on it to counter the book’s weight.

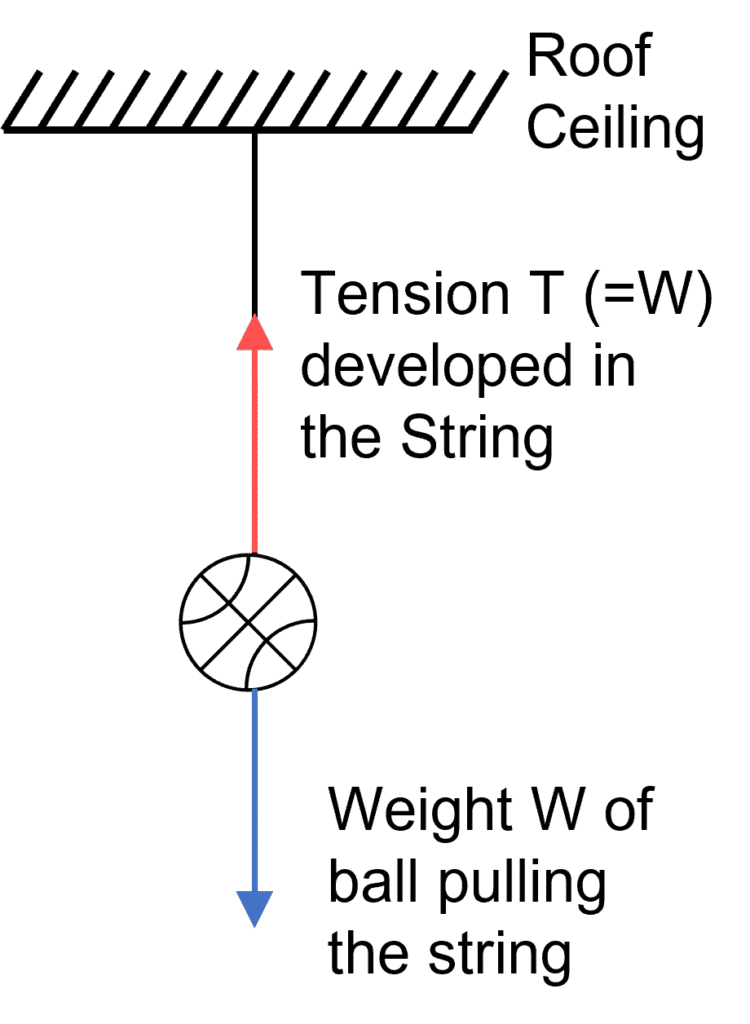

(c) Force of tension in a string: This force is transmitted through a string, rope, or cable when it is pulled tight from opposite ends. The string must be physically attached to and in contact with the object for the tension to act.

2. Non-Contact Forces: These are the forces that can act between two objects even when they are not physically touching each other. They act through empty space via a field.

(d) Gravitational force: This is the force of attraction that exists between any two objects with mass. For example, the Earth pulls us towards its center without needing to touch us, and the planets are held in orbit around the Sun by gravity.

(e) Electrostatic force: This is the force exerted by electrically charged objects on each other. A charged balloon can attract your hair without touching it, and opposite charges attract while like charges repel.

(f) Magnetic force: This is the force exerted between magnetic poles (North and South). A magnet can attract a piece of iron or another magnet from a distance without any physical contact.

Question 4: Give one example in each case where: (a) the force is of contact and (b) Force is at a distance.

Ans: a) Example of a Contact Force:

A common example of a contact force is pushing a heavy box across the floor.

In this case, the force that moves the box is only applied when your hands are physically touching it. The force cannot exist without this direct contact between your hands and the surface of the box. The box only starts moving, stops, or changes direction when this direct push or pull is applied.

(b) Example of a Force at a Distance:

A simple example of a force at a distance is a magnet pulling an iron nail towards it.

Here, the magnet can pull the nail without actually touching it. The magnetic force acts across the empty space between them. You can see the nail jump towards the magnet even when there is a small gap, proving that a physical connection is not needed for this force to work.

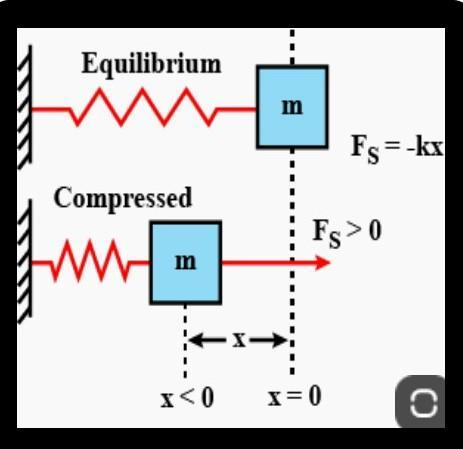

Question 5: (a) A ball is hanging by a thread from the ceiling of the roof. Draw a neat labelled diagram showing the forces acting on the ball and the string. (b) A spring is compressed against a rigid wall. Draw a neat and labelled diagram showing the forces acting on the spring.

Ans:

Question 6: State one factor on which the magnitude of a non – contact force depends. How does it depend on the factor stated by you?

Ans: The strength of a non-contact force is heavily influenced by the distance separating the two objects involved.

This relationship works in the following way:

As the two objects move farther apart, the strength or magnitude of the non-contact force acting between them becomes weaker. Essentially, the force diminishes as the distance grows.

Explanation:

Think of it like the warmth you feel from a campfire. When you are sitting right next to it, the heat (a non-contact force in the form of infrared radiation) is very strong. If you stand up and take several steps back, you immediately feel the heat become less intense. The warmth hasn’t disappeared entirely, but its magnitude has significantly decreased because you have increased your distance from the source.

This principle is a fundamental property of non-contact forces such as gravity, magnetism, and electrical forces. The force doesn’t vanish with distance, but it rapidly loses its intensity, making its effect much less noticeable the farther apart the objects are.

Question 7: The separation between two masses is reduced to half. How is the magnitude of gravitational force between them affected?

Ans: When the distance between two masses is halved, the gravitational force becomes four times stronger.

This happens because gravity follows an inverse square law. The force is proportional to the inverse of the distance squared (F ∝ 1/r²).

If the original distance is ‘r’, halving it makes the new distance ‘r/2’.

Plugging this into the relationship gives:

New Force ∝ 1/(r/2)² = 1/(r²/4) = 4/r²

Since the original force was proportional to 1/r², the new force is four times greater.

Question 8: Define the term ‘force’?

Ans: Force: A Simple Push or Pull. It is something we experience every day.

Force has two key effects:

It Changes Motion: A force can start, stop, speed up, slow down, or change the direction of an object’s movement.

It Changes Shape: A force can bend, stretch, or squash an object, like squeezing a sponge.

We measure force in units called Newtons (N). In simple terms, force is the push or pull that causes change in the world around us.

Question 9: State the effects of a force applied on (i) a non- rigid, and (ii) a rigid body. How does the effect of the force differ in the two cases?

Ans: The Effects of a Force on Different Bodies

When a force acts upon an object, the resulting effect depends significantly on the nature of the object itself. We can broadly categorize these effects by looking at how forces interact with non-rigid bodies and rigid bodies.

(i) Effect of a Force on a Non-Rigid Body

A non-rigid body is one that is flexible or malleable, meaning its particles can be displaced relative to one another. When a force is applied to such a body, its primary effect is a change in the body’s physical dimensions or form.

Key Outcome: Change in Shape and/or Size

For instance, if you pull on both ends of a rubber band, it elongates and becomes thinner. Similarly, when you press and squeeze a lump of clay or dough with your hands, it flattens and spreads out, taking on a new shape. In these examples, the applied force directly overcomes the internal structure of the material, causing a permanent or temporary deformation. The molecules are rearranged, leading to the visible change in form.

(ii) Effect of a Force on a Rigid Body

A rigid body is an idealization in physics where an object is considered to be perfectly solid and unchangeable in shape. In practical terms, objects like a wooden block or a metal rod are treated as rigid because any change in their shape under force is negligible for basic analysis. On such a body, a force does not alter the form but instead affects its movement.

Key Outcome: Change in the State of Motion

This change in the state of motion, also known as a change in velocity, can manifest in several ways:

Initiating Motion: A force can set a stationary body into motion. A gentle push can start a book sliding across a table.

Halting Motion: A force can bring a moving body to a stop. Catching a cricket ball applies a force that counteracts its motion, bringing it to rest in your hand.

Altering Speed: A force can change how fast a body is moving. Pressing the accelerator pedal

Question 10: Give one example in each of the following cases: (a) A force stops a moving body (b) A force moves a stationary body (c) A force changes the size of a body (d) A force changes the shape of a body

Ans:

(a) A force stops a moving body

Example: Applying the brakes of a bicycle. When you are cycling and you squeeze the brake levers, the brake pads apply a frictional force against the wheels. This force acts in the opposite direction to the bicycle’s motion, causing it to slow down and eventually stop.

(b) A force moves a stationary body

Example: Kicking a football that is lying still on the ground. Your foot applies a force to the stationary ball. This force overcomes its inertia and sets it in motion, making it move across the field.

(c) A force changes the size of a body

Example: Squeezing a sponge. When you compress a sponge with your hands, the force you apply pushes its particles closer together. This causes the sponge to temporarily decrease in size or volume.

(d) A force changes the shape of a body

Example: Stretching a rubber band. When you pull on both ends of a rubber band, the applied force causes the rubber band to elongate and become longer and thinner, thus permanently or temporarily changing its original shape.

Question 11: State Newton’s first law of motion. Why is it called the law of inertia?

Ans: Newton’s first law of motion states that an object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external unbalanced force.

It is called the law of inertia because it describes the natural tendency of all objects to resist any change in their state of rest or motion.

The word “inertia” refers to this inherent property of matter to continue in its existing state unless compelled to change by an outside force.

Question 12: Define the term linear momentum. State its S.I. unit.

Ans: Linear momentum measures an object’s “quantity of motion.” It is the product of an object’s mass and its velocity.

Formula:

p = m × v

Here, p is momentum, m is mass (in kg), and v is velocity (in m/s).

Key Points:Momentum is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction.

Its SI unit is kg·m/s.

This explains phenomena like gun recoil, rocket motion, and collisions.

In short, momentum helps us understand and predict motion during interactions between objects.

Question 13: (a) Write an expression for the change in momentum of a body of mass m moving with velocity v if (i) v ≪ c and (ii) v ⟶ c. (b) State the condition when the change in the momentum of a body depends only on the change in its velocity.

Ans: (a) Expression for change in momentum (p):

Momentum is given by

p=mv for classical cases, but relativistically it is

p=mv/(1−v2/c2)2

(i) When v≪c

The relativistic factor

γ≈1, so

p≈mv

Change in momentum:

Δp≈mΔv

(ii) When

v→c:

The relativistic factor

γ≫1, so

p=mv/(1−v2/c2)2

Change in momentum:

Δp≈very large increase for small Δv due to γ factor.

(b) Condition when change in momentum depends only on change in velocity:

This happens when mass

m is constant and velocity

v≪c, so that

Δp=mΔv.

Question 14: How is force related to the momentum of a body?

Ans: A force is what changes an object’s momentum. Momentum is the quantity of motion an object has.

The stronger the force, the faster this change in momentum happens.

This core idea is Newton’s Second Law, summed up by the formula:

Force = (Final Momentum – Initial Momentum) / Time

or

F = (mv – mu) / t

Question 15: State Newton’s Second law of motion. Under what condition does it take the form F = ma?

Ans: Newton’s Second Law of Motion states that the rate of change of momentum of a body is directly proportional to the applied external force and takes place in the direction in which the force acts.

In simpler terms, momentum (which is the product of an object’s mass and velocity) changes when a net force is applied to it. The law highlights that it’s not just the change in speed, but the change in this specific quantity (momentum) that is crucial.

Mathematically, if momentum is denoted by p, and p = m × v, then Newton’s Second Law is expressed as:

Force ∝ Rate of change of momentum

Or, F ∝ dp/dt

Which becomes F = k × (dp/dt)

Where ‘k’ is the constant of proportionality.

The Condition for F = ma

The familiar form, F = ma, is a special case of the broader law. It holds true under one specific and very common condition:

When the mass of the body remains constant.

Here is the step-by-step derivation under this condition:

Starting from the fundamental statement:

F ∝ dp/dt

We know momentum p = mass × velocity = m × v.

So, F ∝ d(mv)/dt

If mass ‘m’ is constant, it can be taken out of the derivative. Therefore:

F ∝ m × (dv/dt)

We know that the rate of change of velocity (dv/dt) is acceleration ‘a’. Substituting this, we get:

F ∝ m × a

By choosing appropriate units for force (like the Newton in the SI system), the constant of proportionality becomes 1. This gives us the well-known equation:

F = m × a

Question 16: Complete the following sentences: (a) Mass X change in velocity = ….. x time interval. (b) The mass of a body remains constant till the velocity of body is……

Ans:

(a) Mass × change in velocity = Force × time interval.

This equation represents the Impulse-Momentum Theorem.

Mass × change in velocity is the change in momentum.

Force × time interval is the impulse.

The theorem states that the impulse applied to an object equals its change in momentum. This explains why, to reduce the force of an impact (like catching a ball), we increase the time over which the stop occurs.

(b) The mass of a body remains constant till the velocity of body is much less than the velocity of light.

This statement distinguishes between classical physics and modern physics (Einstein’s relativity).

In everyday life and classical mechanics, mass is considered a constant property of an object.

However, at speeds approaching the speed of light, Einstein’s theory of relativity shows that an object’s relativistic mass increases.

Therefore, the rule of constant mass is a highly accurate approximation only for velocities much lower than the speed of light.

Question 17: Prove the force = mass x acceleration. State the condition when it holds

Ans:

Proof of

F=m⋅a (Newton’s Second Law):

Newton’s second law states that the net force applied on an object is directly proportional to the rate of change of momentum of the object.

Momentum

p=m⋅v

Rate of change of momentum:

F∝dp/dt=d(mv)/dt

If mass

m

m is constant,

F∝m⋅dv/dt =m⋅a

Choosing suitable units, proportionality becomes equality:

F=m⋅a holds when the mass of the body remains constant during the motion.

Question 18: Name the S.I. unit of (a) momentum, (b) rate of change in momentum.

Ans: (a) The S.I. unit of momentum is kg m/s.

Momentum is mass times velocity. Mass is in kilograms (kg) and velocity is in metres per second (m/s). Multiplying these units gives kilogram-metre per second (kg m/s).

(b) The S.I. unit of the rate of change in momentum is the newton (N).

Newton’s second law states that force equals the rate of change of momentum. Force is measured in newtons (N), so the rate of change of momentum also has the unit newton (N), which is the same as kg m/s².

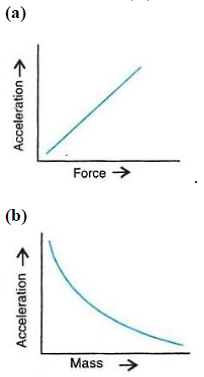

Question 19: State the relationship between force, mass and acceleration. Draw graphs showing the relationship between: (a) Acceleration and force for a constant mass. (b) Acceleration and mass for a constant force.

Ans:

Question 20: A rocket is moving at a constant speed in space by burning its fuel and ejecting out the burnt gases through a nozzle. Answer the following: (a) Is there any change in the momentum of the rocket? If yes, what causes the change in momentum? (b) Is there any force acting on the rocket? If yes, how much?

Ans:

(a) Yes, there is a change in the momentum of the rocket.

This change in momentum is caused by the principle of conservation of momentum. The rocket carries fuel, which is a form of stored mass and energy. When this fuel is burned and the resulting hot gases are ejected backwards at high speed through the nozzle, these gases gain momentum in the backward direction. For the total momentum of the system (rocket + ejected gases) to remain constant (or conserved), the rocket itself must gain an equal amount of momentum in the forward direction. So, the continuous ejection of mass in one direction is what directly causes the continuous change in the rocket’s momentum in the opposite direction.

(b) Yes, there is a force acting on the rocket.

The force acting on the rocket is explained by Newton’s Second Law of Motion. The rate at which the rocket’s momentum changes is directly equal to the force acting on it. This force is known as the thrust.

We can calculate the magnitude of this thrust force. If the rocket ejects burnt gases at a constant rate (mass per second, denoted as dm/dt) and with a constant exhaust speed (u) relative to the rocket, then the thrust (F) acting on the rocket is given by:

F = u * (dm/dt)

It’s important to note that dm/dt is a negative quantity for the rocket (since its mass is decreasing), but the thrust force F is a positive value acting in the forward direction, opposite to the direction of the ejected gases.

Question 21: State Newton’s third law of motion.

Ans: Newton’s third law of motion states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.This means that if one object exerts a force on another object, the second object simultaneously exerts a force of equal magnitude but in the opposite direction on the first object.

Explanation with an example:

When you push against a wall (action), the wall pushes back on you with a force of equal strength in the opposite direction (reaction). Another common example is the motion of a rocket — the rocket pushes exhaust gases downward (action), and the gases push the rocket upward (reaction).

Question 22: Name and define the S.I. and C.G.S. unit of force. How are they related?

Ans: S.I. Unit of Force:

The S.I. unit of force is the newton (N).

Definition: One newton is the force that produces an acceleration of 1 m/s² on a mass of 1 kg.

1N=1kg⋅m/s 2

C.G.S. Unit of Force:

The C.G.S. unit of force is the dyne.

Definition: One dyne is the force that produces an acceleration of 1 cm/s² on a mass of 1 gram.

1dyne=1g⋅cm/s 2

Relationship between newton and dyne:

1N=1kg⋅m/s 2 =1000g×100cm/s 2 =10 5 g⋅cm/s 2=10 5 dyne

So,

1N=10 *5 dyne

Question 23: Define newton (the S.I. unit of force).

Ans: The newton (symbol: N) is the S.I. unit of force.

It is defined as the force required to accelerate a mass of one kilogram at a rate of one metre per second squared.

This definition comes directly from Newton’s second law of motion:

Force = mass × acceleration

Therefore,

1 N = 1 kg × 1 m/s²

Question 24: Define 1 kgf how is it related to newton?

Ans:

1 kgf is the weight of a 1 kg mass under Earth’s gravity.

Since weight is a force, and force (in newtons) is mass times acceleration, we use the standard gravitational acceleration (g = 9.8 m/s²).

Therefore, the relationship is:

1 kgf = 9.8 N

Question 25: Explain what is understood by the following statement: 1 kilogram force (kgf) = 9.8 newton’

Ans: The statement “1 kgf = 9.8 N” defines the relationship between a kilogram-force and a newton.

A kilogram-force (kgf) is the weight of a 1 kg mass under Earth’s gravity. In other words, it is the force of gravity acting on one kilogram.

A newton (N) is the standard scientific unit of force. It is the force needed to accelerate a 1 kg mass by 1 meter per second every second (1 m/s²).

The number 9.8 comes from the average acceleration due to gravity on Earth (g ≈ 9.8 m/s²).

Since force = mass × acceleration, the force of gravity on a 1 kg mass is:

1 kg × 9.8 m/s² = 9.8 N.

So, 1 kgf is the force equivalent to 9.8 newtons.

Question 26: How can you feel a force of 1 N?

Ans: We can understand and feel a force of 1 Newton (N) by relating it to everyday actions. The scientific definition—the force needed to accelerate a 1 kg object at 1 meter per second squared—can be hard to imagine. So, let’s use a simple and common example:

By holding a small apple in your hand.

When you hold a medium-sized apple (weighing about 100 grams or 0.1 kg) and feel it resting on your palm, the force of gravity pulling it down is approximately 1 Newton.

How it works: The Earth’s gravity pulls on the apple. Your hand provides an equal and opposite upward force to stop it from falling. This balanced force you are exerting (and feeling) is about 1 N.

So, the next time you pick up an apple, you are not just holding a fruit; you are experiencing a fundamental unit of force. It’s a gentle, familiar push or pull that we encounter constantly in our daily lives without even realizing it.

Question 27: Complete the following:

(a) Force = mass x ……..

(b) 1 N = ……… dyne

(c) 1 N = ………… kgf (approx.)

(d) newton is the unit of ………

Ans: (a) Force = mass × acceleration

(b) 1 N = 10⁵ dyne

(c) 1 N = 0.102 kgf (approx.)

(d) newton is the unit of force

MULTIPLE CHOICE TYPE:

Question 1: 1. which of the following is not the force at a distance:

(a) electrostatic force

(b) gravitational force

(c) frictional force

(d) magnetic force.

Ans: Frictional force

Question 2: Newton’s second law of motion applicable in all conditions is:

(a) F = ∆𝑝 ∆𝑡

(B) F = ma

(C) F = 𝑀∆𝑉 ∆𝑡

(d) all three

Ans: F = ∆𝑝 ∆𝑡

NUMERICALS:

Question 1: A body of mass 1 kg is thrown vertically up with an initial speed of 5 m s-1. What is the magnitude and direction of force due to gravity acting on the body when it is at its highest point? Take G = 9.8 n kg

Ans: Step 1: Understanding the situation

A mass of 1 kg is thrown upward with an initial speed of 5 m/s. At the highest point, its velocity becomes zero for an instant, but gravity still acts on it.

Step 2: Force due to gravity

The force of gravity (weight) is given by

F=m×g

where

m=1 kg and

g=9.8 N/kg.

F=1×9.8=9.8 N

Step 3: Direction of force

Gravity always acts vertically downward, regardless of the motion of the body.

Final Answer:

Magnitude: 9.8 N

Direction: Vertically downward

Question 2: A body of mass 1.5 kg is dropped from a height of 12m. What is the force acting on it during its fall? (g = 9.8 m s-2)

Ans:

Step 1: Identify the forces during fall

When the body is falling freely, the only force acting on it is gravity (neglecting air resistance).

Step 2: Apply Newton’s second law

Force = mass × acceleration

Here, acceleration =

g=9.8 m/s 2

Mass m=1.5 kg

Step 3: Calculate the force

F=m×g=1.5×9.8

F=14.7 N

Final Answer:14.7 N

Question 3: Two balls of masses in ratio 1:2 are dropped from the same height find: (a) the ratio between their velocities when they strike the ground, and (b) the ratio of the forces acting on them during motion.

Ans: (a) Ratio of velocities when they strike the ground

When two objects are dropped from the same height, their final velocity upon striking the ground is given by

v= 2gh

This velocity depends only on g and h, not on mass.

Since both balls are dropped from the same height,

v1/v2=1v 2/v1

=1

Answer: 1:1

(b) Ratio of forces acting on them during motion

The only force acting on each ball during free fall is gravity (ignoring air resistance), so

F=mg

Given

m1:m2=1:2

F1F2=m1g/m2g

=12

Answer: 1:2

Final Answer:

(a) 1:1

(b) 1:2

Question 4: A body X of mass 5 kg is moving with velocity 20 m s-1 while another body Y of mass 20 kg is moving with velocity 5 m S-1. Compare the momentum of the two bodies.

Ans:

We are given two bodies, X and Y, with different masses and velocities. The goal is to compare their momentum.

Step 1: Recall the Formula for Momentum

In physics, the momentum (p) of a moving object is calculated by multiplying its mass (m) by its velocity (v). The formula is:

p=m×v

Momentum is a vector quantity, but for this comparison where motion is in a straight line, we can compare their magnitudes directly.

Step 2: Calculate the Momentum of Body X

Mass of X,

mX=5kg

Velocity of X,

vX=20m/s

p X=m X×v X=5×20=100

Step 3: Calculate the Momentum of Body Y

Mass of Y,

mY=20kg

Velocity of Y,

vY=5m/s

p Y =m Y ×v Y=20×5=100

Step 4: Compare the Momenta

We have:

Momentum of X,Momentum of Y,

Since

100=100, the momenta of both bodies are equal.

Final Answer:Both bodies have the same momentum.

Question 5: Calculate the acceleration produced in a body of mass 50g when acted upon by a force of 20 N.

Ans:

Step 1: Note down the given information

Force (F) = 20 N

Mass (m) = 50 g

Step 2: Convert mass into the SI unit

The SI unit of mass is the kilogram (kg).

We know that 1 kg = 1000 g.

Therefore, mass in kg is:

m=50/1000kg

m=0.05kg

Step 3: Recall the relevant formula

According to Newton’s second law of motion:

Force=mass×acceleration

F=m×a

Step 4: Substitute the values into the formula

20N=0.05kg×a

Step 5: Solve for acceleration (a)

To find ‘a’, we rearrange the formula:

a=F/m

a=20/0.05

a=400m/s 2

Final Answer: The acceleration produced in the body is 400 m/s².

Question 6: A car of mass 600 kg is moving with a speed of 10 ms-1 while a scooter of mass 80kg is moving with a speed of 50 m s-1 (a) Compare their momentum (b) which vehicle will require more force to stop it in the (i) same interval of time (ii) same distance.

Ans:

We are given:

Mass of car,

mc=600 kg, Velocity of car,

vc =10 m/s

Mass of scooter,

ms =80 kg, Velocity of scooter,

vs =50 m/s

(a) Compare their momentum

Momentum (p) is calculated as the product of mass and velocity, p=m×v.

Momentum of the car:

Momentum of the scooter:

Comparison:

To compare them, we find the ratio:

pc/ps=6000/4000=3/2=1.5

Conclusion: The car’s momentum is 1.5 times greater than the scooter’s momentum.

(b) Which vehicle will require more force to stop

The force required to stop a moving object depends on how quickly we want to stop it (time) or over what distance we want to stop it.

(i) In the same time interval

The force needed is given by Newton’s second law, which relates force to the rate of change of momentum. For bringing an object to rest, this simplifies to:

F=Change in Momentum/Time Taken

=mvΔt

Since the time interval (Δt) is the same for both, the force required is directly proportional to the momentum of the vehicle (F∝p).

From part (a), we know:

and .Since the car has a greater momentum, the car will require more force to stop in the same amount of time.

(ii) In the same distance

When stopping over the same distance, it is more useful to consider the work-energy principle. The work done by the stopping force equals the change in the vehicle’s kinetic energy (KE). The work done is

W=F×s,

where

s is the stopping distance.

F×s= 2/1 mv 2

Since the distance (s) is the same for both, the force required is directly proportional to the kinetic energy of the vehicle (F∝KE).

Let’s calculate the kinetic energy for each:

Kinetic Energy of the car:

KEc=12×mc×vc2=12×600×(10)2=300×100=30,000 J

Kinetic Energy of the scooter:

KEs=12×ms×vs2=12×80×(50)2=40×2500=100,000 J

Comparing the kinetic energies, the scooter has significantly more kinetic energy than the car (100,000 J>30,000 J).

Therefore, the scooter will require more force to stop within the same distance.

Question 7: How much acceleration will be produced in a body of mass 10 kg acted upon by a force of 2 kgf? (g = 9.8 ms-2)

Ans:

Step 1: Understand the given information

Mass of the body,

m=10kg

Force acting on the body,

F=2kgf

Acceleration due to gravity,

g=9.8m/s 2

Step 2: Convert the force from kgf to Newtons

The unit “kgf” stands for kilogram-force. By definition, 1 kgf is the force due to gravity on a mass of 1 kg. Therefore,

1kgf=1kg×gm/s 2 =9.8N

So, a force of 2 kgf is equivalent to:

F=2kgf=2×9.8N=19.6N

Step 3: Apply Newton’s second law of motion

Newton’s second law states:

F=m×a

Where:

F

F is the net force in Newtons (N),

m

m is the mass in kilograms (kg),

Step 4: Calculate the acceleration

We have

F=19.6N and

m=10kg.

Substituting these values into the formula:

a=F/m=19.6/10m/s2

Final Answer:

The acceleration produced in the body is 1.96m/s 2

Question 8: Two bodies have masses in the ratio 3:4, when a force is applied on the first body, it moves with an acceleration of 6 ms-2. How much acceleration will the same force produce in the other body?

Ans:

Step 1: Understand the Given Information

We are told that:

The ratio of the masses of two bodies is

m1:m2=3:4

The first body experiences an acceleration

a1 =6m/s 2 .

The same force F acts on both bodies.

Step 2: Apply Newton’s Second Law

Newton’s second law states that Force = mass × acceleration, or

F=ma.

Since the force is the same for both bodies, we can set their force equations equal to each other:

F=m1a1=m2a2

Step 3: Substitute the Mass Ratio and Given Acceleration

Let’s use a common factor

k to represent the masses based on the given ratio. So,

m1=3k and

m2 =4k.

Substituting these into the equation

m1a1=m2a2 :(3k)×6=(4k)×a 2

Step 4: Solve for the Unknown Acceleration a2

Perform the multiplication:

18k=4k×a 2

Since k is not zero, we can divide both sides of the equation by

k to eliminate it:

18=4×a 2

Now, solve for a2 by dividing both sides by 4:

a2=18/4=4.5

Final Answer: The acceleration of the second body is 4.5m/s2

Question 9: A cricket ball of mass 100 g strikes the hand of a player with a velocity of 20 ms-1 and is brought to rest in 0.01 s. calculate : (i) the force applied by the hand of the player, (ii) the acceleration of the ball

Ans: Given:

Mass of cricket ball,

m=100 g=0.1 kg

Initial velocity,

u=20 m/s

Final velocity,

v=0 m/s

Time,

t=0.01 s

(i) Force applied by the hand of the player

We know:

F=m⋅a

But

a is unknown. First find acceleration using

a= t/v−u

a=0−20/0.01

=−20/0.01

=−2000m/s2

The negative sign indicates retardation.

Magnitude of acceleration: 2000m/s

Now,

F=m⋅a=0.1×2000=200 N

So,200 N

The force applied by the hand is 200 N opposite to the direction of motion of the ball.

(ii) Acceleration of the ball

We already computed acceleration:

a=−2000 m/s 2

Magnitude = 2000m/s2, direction opposite to initial velocity.

So,−2000m/s2

(The negative sign is important for vector nature; if only magnitude is asked, it’s

2000m/s2)

Final Answer:

(i) 200 N

(ii) −2000m/s

Question 10: A lead bullet of mass 20g, travelling with a velocity of 350 ms-1, comes to rest after penetrating 40 cm in a still target. Find : (i) the resistive force offered by the target and (ii) the retardation caused by it.

Ans: Step 1: Understanding the problem

We are given:

Mass of bullet,

m=20 g=0.020 kg

Initial velocity,

u=350 m/s

Final velocity,

v=0 m/s

Distance penetrated,

s=40 cm=0.40 m

We need to find:

(i) Resistive force F

(ii) Retardation a

Step 2: Find retardation using kinematics

We use the equation:v 2 =u 2 +2as

Substitute values:

0=(350)2+2⋅a⋅0.4

0=122500+0.8a

0.8a=−122500

a=122500/0.8

=−153125 m/s 2

The negative sign indicates retardation.

So magnitude of retardation:

a=1.53125×10 5 m/s 2

Step 3: Find resistive force

From Newton’s second law:

F=m⋅a

F=0.020×153125

F=3062.5 N

Step 4: Final answers: 3062.5 N

1.53125×10 *5 m/s 2

(i) Resistive force = 3062.5 N

(ii) Retardation = 1.53125 × 10⁵ m/s²

Question 11: A body of mass 50g is moving with a velocity of 10 ms-1. It is brought to rest by a resistive force of 10 N. find: (i) the retardation and (ii) the distance that the body will travel after the resistive force is applied.

Ans:

Step 1: Understand the Given Data and Convert Units

First, we must ensure all units are consistent. We’ll use the SI system (meters, kilograms, seconds).

Mass of the body,

m=50g

=50/1000kg

=0.05kg

Initial velocity,

u=10m/s

Final velocity,

v=0m/s (since it is brought to rest)

Resistive force,

F=10N

(i) Find the Retardation

Retardation is the negative acceleration acting on the body.

From Newton’s second law of motion:

F=m⋅a

Where

F is the force,

m is the mass, and

a is the acceleration (which will be negative, i.e., retardation).

We can rearrange this formula to find the acceleration:

a=Fm

Substituting the values:

a=10N/0.05kg

=200m/s2

Since this force is resisting the motion and bringing the object to rest, the acceleration is negative. Therefore, the retardation is 200m/s2 .

Answer for (i):200 m/s 2

(ii) Find the Distance Travelled

We will use the third equation of motion:

v2=u2+2as

Where:

v=0m/s (final velocity)

u=10m/s (initial velocity)

a=−200m/s 2

(acceleration/retardation, negative because it opposes motion)

s=? (distance travelled)

Substitute the values into the equation:

(0)2=(10)2+2×(−200)×s

0=100−400s

400s=100

s=100/400

=0.25m

Answer for (ii):0.25 m

The body will travel a distance of 0.25 meters (or 25 cm) after the resistive force is applied before coming to re

Question 12: A uniform car of mass 500g travels with a uniform velocity of 25 m s-1 for 5 s. The brakes are then applied and the car is uniformly retarded and comes to rest in further 10 s calculate: (a) the retardation, (b) the distance which the car travels after the brakes are applied, (c) The force exerted by the brakes.

Ans: Mass

m=500 g=0.5 kg

Initial velocity

u=25 m/s

Final velocity

v=0 m/s

Time for stopping after brakes applied

t=10 s

(a) Retardation

a=v−ut

=0−25/10

=−2.5m/s

So retardation = 2.5m/s

(b) Distance after brakes applied

s=ut+12at2

s=25×10+1/2×(−2.5)×102

s=250−125=125 m

(c) Force exerted by brakes

F=m×a

Here

a is retardation magnitude =2.5m/s

F=0.5×2.5=1.25 N

Final answers:(a) 2.5 m/s

(b) 125 m

(c) 1.25 N

Question 13: A truck of mass 5 × 103kg starting from rest travels a distance of 0.5 km in 10 s when a force is applied on it calculate: (a) the acceleration acquired by the truck and (b) the force applied

Ans:

Given:

Mass, m=5×10/3kg

Initial velocity, u=0

Distance, s=0.5km=500m

Time, t=10s

(a) Acceleration

Using the equation of motion:

s=ut+1/2at2

500=0+1/2×a×(10)2

500=50a

a=10m/s 2

(b) Force applied

F=m×a

F=5000×10

F=5×10 *4 N

Final Answer:

(a) 10m/s2,

(b) 50000N

Question 14: A force of 10 kgf is applied on a body of mass 100 g initially at rest for 0.1s calculate: (a) the momentum acquired by the body, (b) the distance travelled by the body in 0.1s. Take g = 10 N kg-1

Ans: Step 1: Understand the given data

Force

F=10 kgf

Mass

m=100 g=0.1 kg

Initial velocity

u=0

Time

t=0.1 s

g=10 N/kg

We know:

1 kgf=g N

10 kgf=10×10 N=100 N.

Step 2: Find acceleration

From Newton’s second law:

F=ma

100=0.1×a

a=100/0.1

=1000m/s2

Step 3: Momentum acquired

Final velocity after 0.1 s:

v=u+at=0+1000×0.1=100 m/s

Momentum

p=mv:

p=0.1×100=10 kg m/s

So (a) 10 kg m/s.

Step 4: Distance travelled in 0.1 s

Using

s=ut+1/2at2

s=0+1/2×1000×(0.1)2

s=500×0.01=5 m

So (b) 5 m.

Final answers:10 kg m/s, 5 m

EXERCISE – 1(B)

Question 1: State the condition when a force produces (a) translational motion, (b) rotational motion, in a body

Ans:

(a) Translational motion:

A force produces translational motion when it is applied through the centre of mass of a free body. This causes the body to move in a straight line in the direction of the force without any rotation.

(b) Rotational motion:

A force produces rotational motion when it is applied away from the centre of mass (at a perpendicular distance) and not through it. This creates a turning effect, called torque, which makes the body rotate about a fixed point or axis.

Question 2: Define moment of force and state its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Moment of force is the measure of the turning effect produced by a force about a pivot point. It is calculated as the product of the force and the perpendicular distance from the pivot to the line of action of the force.

Its S.I. unit is the newton-metre (N m).

Question 3: Is moment of force a scalar or a vector?

Ans: Moment of force (or torque) is a vector quantity.

It has both magnitude and direction, and its direction is perpendicular to the plane of rotation as given by the right-hand rule.

Question 4: State two factor on which moment of force about a point depends.

Ans: The turning effect or the moment of a force about a specific point depends on the following two main factors:

The Magnitude of the Force Applied: The larger the force applied, the greater is its turning effect or moment. For example, it is easier to loosen a tight nut by applying a greater push or pull on the spanner.

The Perpendicular Distance of the Force’s Line of Action from the Pivot Point: The moment is greater when the force is applied at a larger perpendicular distance from the pivot (the point of rotation). This is why a longer spanner is more effective in turning a nut than a shorter one with the same amount of force.

Question 5: When does a body rotate? State one way to change the direction of rotation of a body. Give a suitable example to explain your answer.

Ans:

When does a body rotate?

A body rotates when a net torque (or turning effect) acts on it. This happens when a force is applied away from its pivot point or centre of mass, creating a turning effect.

One way to change the direction of rotation:

The direction of rotation can be changed by reversing the direction of the applied force.

Example:

Consider opening and closing a door. To open it, you push it forward. To close it (reverse the rotation), you pull it backward. The hinge acts as the pivot, and changing the push to a pull reverses the torque, thus changing the direction in which the door rotates.

Question 6: Write the expression for calculating the moment of force about a given a axis.

Ans: The moment of force (or torque) is calculated as:

τ = F × d

Where:

τ is the moment or torque.

F is the applied force.

d is the perpendicular distance from the pivot point to the force’s line of action.

In its vector form, torque is the cross product of the position vector (r) and the force vector (F):

τ = r × F

Question 7: State one way to reduce the moment of given force about a given axis of rotation.

Ans: One effective way to reduce the moment of a given force about a given axis of rotation is to decrease the perpendicular distance between the line of action of the force and the axis of rotation.

Explanation:

Since the moment of force (or torque) is calculated as the product of the force and the perpendicular distance from the axis (Moment = Force × Perpendicular Distance), reducing this distance directly lowers the turning effect. For example, to close a heavy door, pushing near the hinges (which reduces the distance) requires much more effort than pushing at the handle (which maximizes the distance). Therefore, to reduce the moment, you would do the opposite and apply the force closer to the pivot point.

Question 8: What do you understand by the clockwise and anticlockwise moment of force? When is it taken positive?

Ans:

Clockwise Moment:

A force causing rotation in the direction of a clock’s hands.

Sign Convention: Negative (-)

Anticlockwise Moment:

A force causing rotation opposite to a clock’s hands.

Sign Convention: Positive (+)

This standard sign convention ensures consistency in calculations for rotational equilibrium.

Question 9: Why is it easier to open a door by applying the force at the free end of it?

Ans: We push a door near its handle to use leverage.

The hinges are the pivot point. Pushing farther from this pivot, like at the handle, creates more turning force (torque) with the same effort. This makes the door easy to open.

If you push close to the hinges, the distance is short, and you need to push much harder. It’s the same principle as using a long wrench to loosen a tight nut—a longer tool makes the job easier.

Question 10: The stone of hand flour grinder is provided with a handle near its rim. Give a reason.

Ans: The handle is provided near the rim of the hand flour grinder’s stone to make the grinding process easier and more efficient.

The reason for this is based on the principle of turning effect of force, also known as torque. Torque is the measure of how much a force acting on an object causes that object to rotate. It is calculated by multiplying the force applied by the distance from the pivot point (in this case, the center of the stone).

Force Applied at the Rim: When you apply a force at the handle near the rim, you are applying it at the greatest possible distance from the central pivot.

Increased Torque: Because the distance is larger, even a small push or pull from your hand creates a larger turning effect (torque) on the heavy stone.

Easier to Rotate: This larger torque makes it much easier to set the heavy stone into a rotating motion and maintain it, requiring less effort from the person grinding.

Question 11: It is easier to turn the steering wheel of a large diameter then that of a small diameter. Give reason.

Ans: Placing the handle near the rim makes grinding easier because of torque.

Torque is the force that causes turning. It is stronger when the distance from the pivot point (the axle) is greater.

A handle at the rim gives you the longest possible distance. This means you can use much less hand force to produce the same turning force needed for grinding.

If the handle were closer to the center, you would have to push much harder to get the stone to turn.

Question 12: A spanner (or wrench) has a long handle. Why?

Ans:

A spanner has a long handle to increase the turning force (torque). A longer handle allows you to apply less effort to loosen or tighten a stubborn nut or bolt.

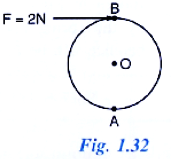

Question 13: A, B and C are the three forces each of magnitude 4 n acting in the plane of paper as shown in Fig. 1.30. The point O lies in the same plane.

(i) Which force has the least moment about O? Give a reason.

(ii) which force has the greatest moment about O? Give a reason.

(iii) Name the forces producing (a) Clockwise, (b) anticlockwise moments.

(iv) what is the resultant torque about the point O?

Ans:

(i) Force with least moment: Force B

Reason: Force B passes through point O, so its perpendicular distance is zero. Hence, its moment is zero.

(ii) Force with greatest moment: Force C

Reason: Force C has the largest perpendicular distance from point O compared to A and B.

(iii)(a) Clockwise moment: Force A

(b) Anticlockwise moment: Force C

(iv) Resultant torque about O:

Moment of A (clockwise) =

4×sin(60∘)×2

Moment of C (anticlockwise) =Resultant torque = anticlockwise≈ (anticlockwise)

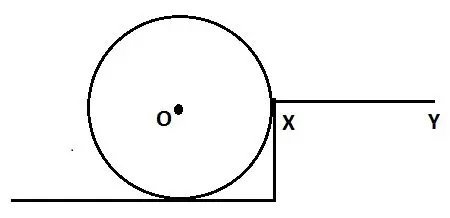

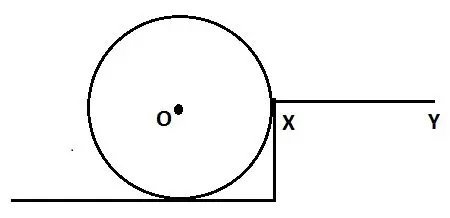

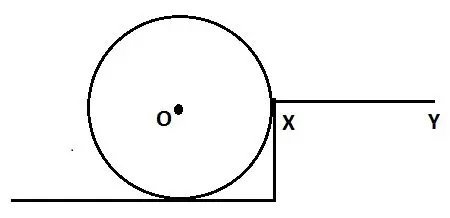

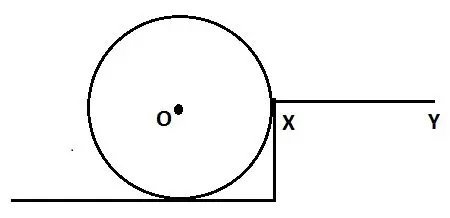

Question 14: The adjacent diagram (Fig. 1.31) Shows a heavy roller, with its axle at O, which its axle at O, which is to be raised on a pavement XY by applying a minimum possible force. Show by an arrow on the diagram the point of application and the direction in which the force should be applied.

Ans:

Question 15: A body is acted upon by two forces each of magnitude F, but in opposite direction. State the effect of the forces if (a) both forces act at the same point of the body. (b) the two forces act at two different point of the body at a separation r.

Ans: (a) When both forces act at the same point:

The two equal and opposite forces will cancel each other out.

The net force on the body is zero, so there is no translational motion.

However, if the forces are collinear, there is no rotation either.

Effect: The body remains in equilibrium.

(b) When the two forces act at different points separated by distance r:

The net force is still zero, so there is no translational motion.

But since the forces are equal, opposite, and parallel but not collinear, they form a couple.

Effect: The couple produces a torque of magnitude

τ=F×r, causing the body to rotate.

Question 16: Draw a neat labelled diagram to show the direction of two forces acting on a body to produce rotation in it. Also mark the point about which rotation takes place, by the letter O.

Ans: A body rotates when two equal, opposite, and parallel forces act on it. This pair of forces is called a couple.

Labelled Diagram:

Forces: Two forces (F) of equal magnitude act in opposite directions (shown by arrowheads).

Point of Rotation (O): The point marked ‘O’ is the center of the body, about which it rotates.

Rotation: The body rotates in a clockwise direction due to this couple.

Question 17: What do you understand by the term couple? State its effect. Give two examples of couple action in our daily life.

Ans:

A couple is a pair of two equal and parallel forces that are opposite in direction and do not act along the same line of force.

Effect:

The sole effect of a couple is to produce or tend to produce rotation of an object. It does not cause any linear motion (i.e., it does not make the object move from one place to another).

Examples in Daily Life:

Turning a Tap: When you open or close a water tap, you apply two equal and opposite forces with your thumb and fingers. This creates a couple that rotates the tap.

Steering a Car: Your hands apply a pair of forces on the steering wheel—one hand pushes up while the other pulls down. This couple causes the steering wheel to rotate.

Question 18: Define the moment of a couple. Write its S.I. unit.

Ans:

The moment of a couple is the turning effect produced by two equal and opposite parallel forces, whose lines of action do not coincide.

It is calculated as the product of one of the forces and the perpendicular distance between their lines of action.

S.I. Unit: Newton-metre (N m)

Question 19: Prove that Moment of couple = Force × couple arm.

Ans:

Step 1: Define a Couple

Equal in magnitude

Opposite in direction

Parallel to each other

Separated by a perpendicular distance called the coucle arm.

Step 2: Describe the Setup

Consider two forces, F and -F, acting at points A and B of a rigid body.

The perpendicular distance between their lines of action is d (the couple arm).

Step 3: Calculate the Total Moment

The moment of a force is given by Force × Perpendicular Distance from the pivot.

Moment due to force F at point A about point B = F × d (This force tends to rotate the body anti-clockwise).

Moment due to force -F at point B about point B = 0 (Since the distance from the pivot point B for this force is zero).

However, a key property of a couple is that its moment is the same about any point. Let’s calculate the total moment about a point O located anywhere.

The total moment (or torque) of the couple is the sum of the moments of both forces about the same point.

Step 4: The Proof

Let’s find the moment about point B for simplicity:

Moment of force -F at B about B = 0.

Moment of force F at A about B = F × d.

Total Moment = F × d + 0 = F × d

This result (F × d) is independent of the location of the pivot point B. If you calculate the moment about point A, or any other point, the net result will always be F × d.

Step 5: Final Statement

Therefore, it is proven that the moment of a couple is the product of one of the forces and the perpendicular distance (couple arm) between them.

Moment of Couple = Force × Couple Arm

Question 20: What do you mean by equilibrium of a body?

Ans: The equilibrium of a body is the state in which the body is either at rest or moving with a constant velocity.

For a body to be in equilibrium, two main conditions must be satisfied:

Translational Equilibrium: The net force acting on the body must be zero. This means there is no change in its linear motion.

ΣF = 0 (Sum of all forces is zero)

Rotational Equilibrium: The net torque (moment of force) acting on the body about any point must be zero. This means there is no change in its rotational motion.

Στ = 0 (Sum of all torques is zero)

In simple terms, a body in equilibrium experiences no acceleration—neither linear nor angular.

Question 21: State the condition when a body is in (i) static (ii) dynamic, equilibrium. Give one example each of static and dynamic equilibrium.

Ans: (i) Static Equilibrium

A body is in static equilibrium when it is at rest and the net force and net torque acting on it are zero.

Example: A book lying on a table.

(ii) Dynamic Equilibrium

A body is in dynamic equilibrium when it is moving with constant velocity (constant speed in a straight line) and the net force and net torque acting on it are zero.

Example: A parachutist descending with a constant terminal velocity.

Question 22: State two condition for a body acted upon by several forces to be in equilibrium.

Ans:

For a body to be in equilibrium:

Net Force is Zero: The sum of all forces acting on the body is zero, preventing linear acceleration.

Net Torque is Zero: The sum of all torques (turning effects) about any point is zero, preventing rotational acceleration.

Question 23: State the principal of moments. Give one device as application of it.

Ans: Principle of Moments:

It states that for a body in equilibrium, the sum of the clockwise moments about a point is equal to the sum of the anticlockwise moments about the same point.

Application:

A beam balance is a common device that works on this principle.

Question 24: Describe a simple experiment to verify the principle of moments, if you are supplied with a metre rule, a fulcrum and two springs with slotted weights.

Ans:

Aim: To verify the principle of moments (sum of clockwise moments = sum of anticlockwise moments).

Apparatus: Metre rule, fulcrum (stand), two springs, slotted weights.

Procedure:

Suspend the metre rule from the fulcrum at its centre of gravity (usually the 50 cm mark) so that it is balanced and horizontal.

Hang one spring (with a slotted weight, e.g., 50 g) on the left side of the rule at a certain distance (e.g., 30 cm mark). This creates an anticlockwise moment.

On the right side, hang the second spring and adjust its position until the rule balances horizontally again.

Note the distance of the second weight from the fulcrum. This creates a clockwise moment.

Observation and Calculation:

Let the weight on the left (W₁) create the anticlockwise moment.

Anticlockwise moment = W₁ × d₁

Let the weight on the right (W₂) create the clockwise moment.

Clockwise moment = W₂ × d₂

Verification:

You will find that W₁ × d₁ = W₂ × d₂.

Repeat the experiment by changing weights and their positions. In all cases, the sum of clockwise moments will equal the sum of anticlockwise moments, thus verifying the principle.

MULTIPLE CHOICE TYPE:

Question 1: The moment of a force about a given axis depends:

(a) only on the magnitude of force

(b) only on the perpendicular distance of force from the axis.

(c) neither on the force nor on the perpendicular distance of force from the axis

(d) both on the force and its perpendicular distance from the axis.

Ans:

The moment of a force about a given axis depends on both on the force and its perpendicular distance from the axis. Hint: Moment of force = Force x Perpendicular distance

Question 2: A body is acted upon by two unequal forces in opposite directions, but not in the same line. The effect is that:

(a) the body will have only the rotational motion

(b) the body will have only the translational motion

(c) the body will have neither rotational motion nor translational motion.

(d) the body will have rotational as well as translational motion.

Ans: (a) The body will have rotational as well as translational motion.

NUMERICALS

Question 1: The moment of a force of 10 N about a fixed point O is 5 N m. Calculate the distance of the point O from the line of action of the force.

Ans:

Step 1: Understanding the Concept

The moment of a force (or torque) about a point is defined as the product of the force’s magnitude and the perpendicular distance from the point to the line of action of the force. The formula is:

Moment=Force×Perpendicular Distance

τ=F×d

Where:

τ is the moment of force (in Newton-meter, N m)

F is the magnitude of the force (in Newton, N)

d is the perpendicular distance (in meters, m)

Step 2: Identifying the Given Values

From the problem statement:

Moment,

τ=5N m

Force,

F=10N

Perpendicular distance,

d=? (This is what we need to find)

Step 3: Rearranging the Formula

We need to find the distance d. Rearranging the standard formula:

d= F/τ

Step 4: Substituting the Values

Substitute the given values into the formula:

d= 10N5N m

Step 5: Calculating the Result

d=0.5m

Final Answer:

The distance of point O from the line of action of the force is 0.5 meters.

Question 2: A nut is opened by a wrench of length 10 cm. if the least force required is 5.0 N, find the moment of force needed to turn the nut.

Ans:Length of wrench,

r=10 cm=0.1 m

Least force required,

F=5.0 N

Moment of force

=r×F

=0.1×5.0

The moment of force needed is 0.5 N·m.

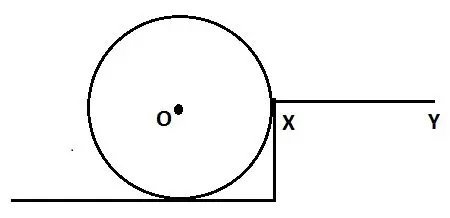

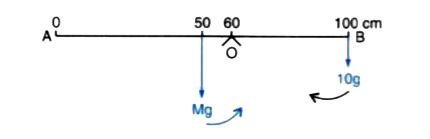

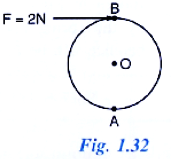

Question 3: A Wheel of diameter 2 m is shown in Fig. 1.32 with axle at O. A force F = 2 N is applies at B in the direction shown in figure. Calculate the moment of force about (i) Centre O, and (ii) point A.

Ans:

Given:

Wheel diameter = 2 m → radius

r=1 m

Force

F=2 N at point B, tangential to the wheel.

θ=90 ∘ between force and radius at B.

(i) Moment of force about center O

Moment=F×r

MO =2×1=2 Nm

Direction: Perpendicular to plane, outward (anticlockwise).2 Nm

(ii) Moment of force about point A

Point A is on the rim, horizontally left from O.

Distance AB = diameter = 2 m.

Force at B is tangential (vertically downward), perpendicular to AB.

MA =F×AB

=2×2=4 Nm

Direction: Same sense (anticlockwise).

4 Nm

Question 4: The diagram in fig.1.33 shows two forces F1 = 5 N and F2 = 3N acting at points A and B of a rod pivoted at a point O, such that OA = 2m and OB = 4m.

Calculate: (i) Moment of force F1 about O.

(ii) Moment of force F2 about O.

(iii) Total moment of the two forces about O.

Ans:

Step 1: Moment of force F1 about O

F1=5 N acts at point A, where

OA=2 m.

The force F1 is perpendicular to the rod, so

Moment=F 1 ×OA=5×2=10 Nm

This is anticlockwise (as seen from the usual diagram orientation).

Step 2: Moment of force F2 about O

F2=3 N acts at point B, where

OB=4 m.

The force F2 is perpendicular to the rod, so

Moment=F2 ×OB=3×4=12 Nm

This is clockwise (opposite direction to F1 ’s moment).

Step 3: Total moment about O

Take anticlockwise as positive:

Total moment=10(anticlockwise)−12(clockwise)

=−2 Nm

Total moment=10 (anticlockwise)−12 (clockwise)=−2 Nm

Negative means net moment is 2 Nm clockwise.

Final answers:

(i) 10 Nm anticlockwise

(ii) 12 Nm clockwise

(iii) 2 Nm clockwise

Question 5: Two forces each of magnitude 10 N act vertically upwards and downwards respectively at the two ends of a uniform road of length 4 m which is pivoted at its mid point as shown in fig 1.34. Determine the magnitude of resultant moment of forces about the pivot O.

Ans: Step 1: Identify forces and positions

Force F1 =10N upward at end A (left side).

Force F2=10N downward at end B (right side).

Rod length 4m, pivot O at midpoint.

Distance from O to each end = 2m.

Step 2: Determine moments

Moment due to

F1 about O:

F1 ×2m clockwise (since upward force on left side pushes rod to turn clockwise).

clockwise.

Moment due to

F2 about O:

F2×2m also clockwise (since downward force on right side also turns rod clockwise).

clockwise.

Step 3: Total moment

Both moments are in the same direction (clockwise), so:

Resultant moment=20+20=40

Final Answer: 40

Question 6: Fig 1.35 shows two forces each of magnitude 10 N acting at the points A and B at a separation of 50 cm, in opposite directions. Calculate the resultant moment of the two forces about the point (i) A, (ii) B and (iii) O, situated exactly at the middle of the two forces.

Ans: Step 1: Understanding the setup

Two forces of 10 N each act at points A and B, 50 cm apart, in opposite directions but parallel (likely forming a couple).

Distance AB = 50 cm = 0.5 m.

Step 2: Moment of a force about a point

Moment = Force × perpendicular distance from the point to the line of action of the force.

(i) About point A

Force at A: line of action passes through A ⇒ moment = 0.

Force at B: 10 N, perpendicular distance from A to line of action of force at B = AB = 0.5 m.

Moment of force at B about A = (clockwise or anticlockwise depending on direction of forces).

Since they are opposite and parallel, the two forces form a couple. But for “resultant moment” about A:

MA =0+5=5

(ii) About point B

Force at B: moment = 0.

Force at A: perpendicular distance from B to line of action of force at A = 0.5 m.

Moment = (same sense as before).

MB=M B

(iii) About point O (midpoint)

Perpendicular distance from O to line of action of force at A = 0.25 m.

Perpendicular distance from O to line of action of force at B = 0.25 m.

Both moments have the same direction (they are a couple).

MO =(10×0.25)+(10×0.25)=

Final Answer:(i)

Question 7: A steering wheel of diameter 0.5 m is rotated anticlockwise by applying two forces each of magnitude 5 N. Draw a diagram to show the application of forces and calculate the moment of couple applied.

Ans:Step 1: Diagram Description

Two equal and opposite forces of 5 N each are applied tangentially at opposite ends of the steering wheel (diameter 0.5 m), perpendicular to the diameter, to produce anticlockwise rotation.

Step 2: Formula for Moment of Couple

Here, the perpendicular distance between the forces = diameter of wheel = 0.5 m.

Step 3: Calculation

Moment of couple = 5×0.5

Final Answer:

The moment of the couple applied is 2.5 N·m.

Question 8: A uniform metre rule is pivoted at its mid-point. A weight of 50 gf is suspended at one end of it. Where should a weight of 100 gf be suspended to keep the rule horizontal?

Ans: Step 1: Understanding the setup

A uniform metre rule has length 100 cm.

Pivot is at the midpoint, i.e., at 50 cm.

Weight of rule acts at midpoint, but since it’s uniform and pivoted at centre, its weight causes no moment (balanced).

50 gf is suspended at one end (0 cm or 100 cm mark). Let’s take it at the 0 cm end.

Step 2: Moments principle

For equilibrium (rule horizontal),

Clockwise moment = Anticlockwise moment

Let the 100 gf weight be suspended at distance x cm from the pivot on the other side of the pivot (so that it balances the 50 gf at the end).

Step 3: Distances from pivot

50 gf at left end: distance from pivot = 50 cm (since pivot at 50 cm, end at 0 cm).

This causes an anticlockwise moment if pivot at centre and 50 gf at left end. Wait — check:

Actually, if pivot at 50 cm, left end is 0 cm mark, so:

Suspended at 0 cm ⇒ distance from pivot = 50 cm toward left.

If 50 gf is on the left of the pivot, its moment tries to turn the rule anticlockwise.

We want 100 gf on the right side to give a clockwise moment.

Step 4: Balancing equation

Anticlockwise moment = Clockwise moment

50×50=100×d

where

d = distance of 100 gf from pivot on right side.

2500=100×d

d=25 cm

Step 5: Position on rule

From pivot at 50 cm, move 25 cm to the right ⇒ at 75 cm mark.

Final answer:75 cm

Question 9: A uniform metre rule balance horizontally on a knife edge placed at the 58 cm mark when a weight of 20 gf is suspended from one end. (i) Draw a diagram of the arrangement (ii) What is the weight of the rule?

Ans:

(i) Diagram Description:

A horizontal metre rule (0 cm to 100 cm) is shown balanced on a knife-edge placed at the 58 cm mark. A weight of 20 gf is suspended from the 0 cm end (the left end). The centre of the rule, and thus its weight W, acts at the 50 cm mark.

(ii) Weight of the rule:

Let the weight of the metre rule be W gf.

The knife-edge is at the 58 cm mark.

The centre of the rule is at the 50 cm mark.

Distance of the rule’s weight (W) from the fulcrum = 58 – 50 = 8 cm (to the right).

The 20 gf weight is at the 0 cm end.

Distance of the 20 gf weight from the fulcrum = 58 – 0 = 58 cm (to the left).

Applying the principle of moments (clockwise moments = anticlockwise moments):

20 gf × 58 cm = W × 8 cm

W = (20 × 58) / 8

W = 1160 / 8

W = 145 gf

Final Answer: The weight of the metre rule is 145 gf.

Question 10: The diagram below (Fig 1.36) Shows a uniform bar supported at the middle point O. A weight of 40 gf is placed at a distance 40 cm to the left of the point O. How can you balance the bar with a weight of 80 gf?

Ans:

Given:

Left weight = 40 gf at 40 cm from O (anticlockwise moment).

Right weight = 80 gf, distance from O = ?

Let the distance of the 80 gf weight from O be x cm (clockwise moment).

Moment equation:

40×40=80×x

1600=80x

x=20 cm

Answer: Place the 80 gf weight 20 cm to the right of point O.

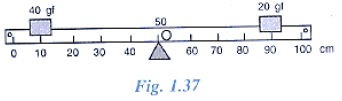

Question 11: Fig 1.37 shows a uniform metre rule placed on a fulcrum at its mid-point O and having a weight 40 gf at the 10 cm mark and a weight of 20 gf at the 90 cm mark. (i) Is the metre rule in equilibrium? If not, how will the rule turn? (ii) How can the rule be brought in equilibrium by using an additional weight of 40 gf?

Ans: (i) Is the metre rule in equilibrium?

No, the metre rule is not in equilibrium.

How will the rule turn?

It will turn clockwise.

Reason: The 40 gf weight at the 10 cm mark (40 cm from the fulcrum O) exerts a larger clockwise moment than the 20 gf weight at the 90 cm mark (40 cm from O).

Calculation:

Clockwise moment = 20 gf × 40 cm = 800 gf-cm

Anticlockwise moment = 40 gf × 40 cm = 1600 gf-cm

Since the anticlockwise moment (1600) is greater than the clockwise moment (800), the rule turns anticlockwise.

(ii) How can it be brought to equilibrium with an extra 40 gf weight?

To achieve equilibrium, the extra 40 gf weight must be placed on the clockwise side (the right side of O) to balance the larger anticlockwise moment.

Position: The extra 40 gf weight should be placed at the 70 cm mark.

Reason: This position is 20 cm from the fulcrum. The clockwise moment it creates (40 gf × 20 cm = 800 gf-cm) will add to the existing 800 gf-cm clockwise moment, making the total clockwise moment equal to the 1600 gf-cm anticlockwise moment.

Question 12: When a boy weighing 20 kgf sits at one end of a 4 m long see saw, it gets depressed at this end. How can it be brought to the horizontal position by a man weighing 40 kgf.

Ans: Given:

Boy’s weight = 20 kgf

Man’s weight = 40 kgf

Boy is at one end.

Solution:

Let the man sit at a distance of x meters from the fulcrum on the same side as the boy (to create a balancing moment).

For the see-saw to be horizontal, the clockwise moment must equal the anticlockwise moment.

The boy creates an anticlockwise moment:

20 kgf × 2 m = 40 kgf·m

The man creates a clockwise moment:

40 kgf × x m

Set the moments equal:

40x = 40

Therefore, x = 1 m

Final Answer:

The man can balance the see-saw by sitting 1 meter away from the fulcrum on the same side as the boy.

Question 13: A physical balance has its arms of length 60 cm and 40 cm. what weight kept on pan of longer arm will balance an object of weight 100 gf kept on other pan?

Ans: Step 1: Understanding the problem

We have a physical balance (like a beam balance) with unequal arms.

Longer arm length

L1 =60 cm

Shorter arm length

L2 =40 cm

A known weight

W2 =100 gf is placed on the shorter arm side.

We need to find the unknown weight

W1 on the longer arm side that balances it.

Step 2: Principle of moments

For the balance to be horizontal:

Anticlockwise moment about the pivot=Clockwise moment about the pivot

If W1 is on the longer arm side, its moment is

W1×L1.

If W2 is on the shorter arm side, its moment is

W2×L2

So:

W1 ×60=100×40 W

Step 3: Solve for

W1=100×40/60

W1=4000/60

W1=400/6

=200/3 gf

W1≈66.67 gf

Step 4: Final answer

66.67 gf

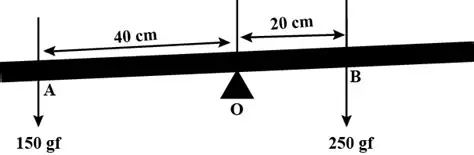

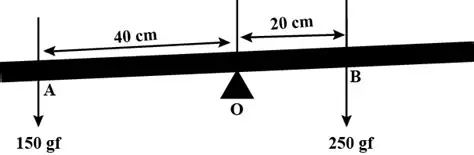

Question 14: The diagram in Fig 1.38 shows a uniform metre rule weighing 100gf, pivoted as its centre O. two weights 150 gf and 250 gf hang from the metre rule as shown. Calculate: (i) the total anticlockwise moment about o, (ii) the total clockwise moment about O, (iii) the difference of anticlockwise and clockwise moments, and (iv) the distance from O where a 100 gf weight should be placed to balance the metre rule.

Ans:

Given:

Metre rule length = 100 cm, pivoted at centre O (50 cm mark).

Weight of rule = 100 gf acts at O (so its moment about O is zero).

150 gf at 40 cm mark (left of O).

250 gf at 70 cm mark (right of O).

(i) Total anticlockwise moment about O

Anticlockwise moment is caused by the 150 gf force on the left side.

Distance from O = 50−40=10 cm

Moment =

Anticlockwise moment=150

(ii) Total clockwise moment about O

Clockwise moment is caused by the 250 gf force on the right side.

Distance from O = 70−50=20 cm

Moment = Clockwise moment=500

(iii) Difference of anticlockwise and clockwise moments

Difference=1500−5000=−3500

Negative means net moment is clockwise.

Magnitude=3500

(iv) Distance from O where a 100 gf weight should be placed to balance

To balance, the 100 gf must provide an anticlockwise moment of 3500 gf·cm to counteract the net clockwise moment.

Let distance from O on the left side =x cm.

Moment = 100×x=3500

x=35 cm

So, place the 100 gf weight 35 cm to the left of O, i.e., at the

50−35=15 cm mark.

Final answers:

(i) 150

(ii) 5000

(iii) 3500

(iv) 15 cm mark (35 cm left of O)

Question 15: A uniform metre rule of weight 10gf is pivoted at its 0 mark. (i) What moment of force depresses the rule? (ii) How can it be made horizontal by applying a least force?

Ans: (i) Moment of force depressing the rule

The weight of the rule (10 gf) acts at its midpoint, i.e., at the 50 cm mark.

Since it is pivoted at the 0 cm mark, the perpendicular distance from the pivot to the line of action of the weight is 50 cm.

Moment=Force×Perpendicular distance

Moment=10 gf×50 cm=500 gf-cm

So, the moment depressing the rule is 500 gf-cm.

(ii) How it can be made horizontal by applying least force

To make the rule horizontal with the least force, the force should be applied at the farthest point from the pivot to maximize the perpendicular distance.

That means applying an upward force at the 100 cm mark.

Let F be the least force.

Balancing moments about the pivot:

F×100=10×50

F=500100=5 gf

F=100/500

=5gf

So, a 5 gf upward force at the 100 cm mark will make it horizontal with the least force

Question 16: A uniform metre scale can be balanced at the 70.0 cm mark when a mass 0.05 kg is hung from the 94.0 cm mark. (a) draw a diagram of the arrangement. (b) Find the mass of the metre scale

Ans: (a) Diagram of the arrangement

The diagram would show:

A pivot (fulcrum) located at the 70.0 cm mark.

The scale’s own weight (W, mass M) acting downwards at its center of gravity, which is at the 50.0 cm mark for a uniform scale.

A 0.05 kg mass hanging from the 94.0 cm mark, acting downwards.

(b) Finding the mass of the metre scale

Anticlockwise moment (due to the scale’s weight):

The weight Mg acts at the 50 cm mark, which is 20 cm to the left of the pivot (70 cm – 50 cm = 20 cm).

Moment = Mg×(20cm)

Clockwise moment (due to the hanging mass):

Moment = 0.05g×(24cm)

Applying the principle of moments:

Mg×20=0.05g×24

The acceleration due to gravity g cancels out from both sides.

M×20=0.05×24

M×20=1.2

M =0.06

Final Answer: 0.06 kg.

Question 17: A uniform metre rule of mass 100 g is balanced on a fulcrum at mark 10 cm by suspending an unknown mass M at the mark 20 cm. (i) Find the value of M (ii) To which side the rule will tilt if the mass m is moved to the mark 10cm? (iii) what is the resultant moment now? (iv) How can it be balanced by another mass of 50g?

Ans:

Given:

Mass of metre rule = 100 g

Length of rule = 1 m=100 cm

Fulcrum at 10 cm

Unknown mass M

Rule is uniform, so its weight acts at 50 cm mark.g

g will cancel in moments, so we can work with masses & distances in cm relative to pivot.

(i) Find M

Clockwise moments (to the right of pivot) =

Due to M at 20 cm: M×(20−10)=M×10 cm

M×(20−10)=M×10 cm (clockwise)

Anticlockwise moments (to the left of pivot) =

Due to rule’s weight (100 g at 50 cm): (anticlockwise)

Balance:

M×10=4000

M×10=4000

M=400 g

M=400 g

(i) Answer:

400 g

400 g

(ii) If mass M

M is moved to 10 cm mark M is now at the pivot (10 cm), so its moment = 0.

Only anticlockwise moment due to rule’s weight (4000 g·cm) remains unopposed.

So the rule will tilt to the left side.

(ii) Answer:

left side

left side

(iii) Resultant moment now

Clockwise moment = 0

Anticlockwise moment = 4000 g·cm

Resultant moment = anticlockwise.

(iii) Answer:

4000 g⋅cm (anticlockwise)

(iv) Balancing with another 50 g mass

Let the 50 g mass be placed at distance x

x cm from the pivot on the right side to create clockwise moment.

Moment needed:

50×x=4000

x=80 cm from pivot

That means from the fulcrum at 10 cm mark, 80 cm to the right ⇒ mark 10+80=90 cm

So, hang 50 g at 90 cm mark.

(iv) Answer:

50 g at 90 cm mark

50 g at 90 cm mark

EXERCISE – 1 (C)

Question 1: Define the term ‘centre of gravity of a body’.

Ans: The centre of gravity of a body is defined as that fixed point through which the entire weight of the body appears to act, regardless of the body’s orientation.

To understand this, imagine a body is made up of a countless number of tiny particles. Each of these particles has its own individual weight due to gravity. These individual weights are essentially parallel forces acting vertically downward. The centre of gravity is the unique point where the resultant of all these parallel forces of weight acts.

For example, in a uniform, symmetrical object like a solid sphere or a rectangular cardboard, the centre of gravity lies at its geometric centre. If you were to support the object at this specific point, it would be in perfect balance and not tip over in any direction because the total weight force acts directly through the point of support.

Question 2: Can the centre of gravity be situated outside the material of the body? Give an example.

Ans: Yes, it is absolutely possible for an object’s center of gravity to be located in the empty space outside its physical material. This concept often seems counterintuitive at first, as we imagine the center of gravity to be a point inside an object, like the middle of a solid ball. However, the center of gravity is not about the object’s shape, but about the average location of its entire weight.

Think of it as the single point where the entire mass of an object can be considered to be concentrated for the purpose of analyzing forces and motion. If you could support an object precisely at this point, it would be perfectly balanced and would not start to rotate under the influence of gravity.

This is why asymmetrical or hollow objects can have a center of gravity in open air. Here are two classic examples:

A Boomerang: A standard ‘V’-shaped boomerang has most of its mass distributed in its two arms. If you try to balance it on your finger, the point of balance—the center of gravity—isn’t on the boomerang itself. It lies at a point in the empty space between the two arms. The gravitational pull from each arm acts as if it is converging at that external point.

A Ring or a Bangle: For a perfectly uniform ring, the center of gravity is precisely at its geometric center, the point in the middle of the hole. No part of the ring’s material is actually at that location, yet that is the point around which its mass is equally distributed in all directions.