The chapter begins by defining Force as an external agent capable of changing a body’s state of rest or motion, or its size and shape. It introduces the concept of Inertia, which is the inherent property of an object to resist changes in its state of motion. Inertia is directly proportional to mass: the greater the mass, the greater the inertia. The chapter then establishes Newton’s First Law of Motion (the Law of Inertia), stating that a body remains at rest or in uniform motion unless acted upon by a net external force. This law naturally leads to the classification of forces into unbalanced forces (which cause acceleration) and balanced forces (which result in zero net force and no change in motion).

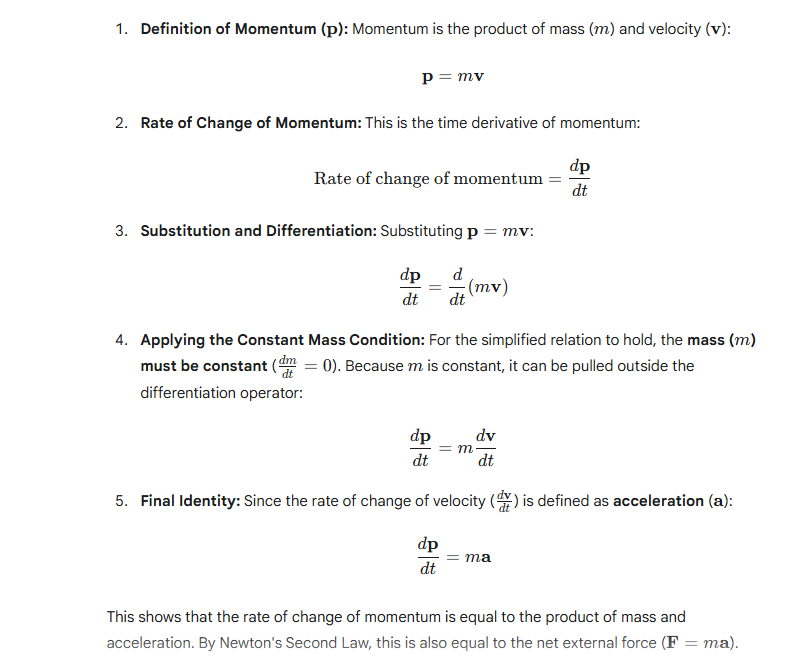

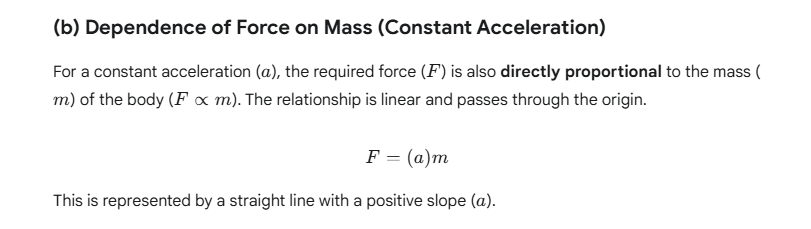

Next, the summary delves into Newton’s Second Law of Motion, which quantitatively relates force to motion. It first defines momentum (p) as the product of mass and velocity . The Second Law then states that the net external force acting on a body is directly proportional to the rate of change of its momentum. For a constant mass, this simplifies to the famous formula: (Force equals mass times acceleration). This is the key equation for solving dynamics problems. The chapter also briefly covers the unit of force, the Newton (N), and its relationship to mass and acceleration.

Finally, the chapter covers Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which is the principle of action and reaction. This law states that for every action force, there is an equal and opposite reaction force. Crucially, the action and reaction forces always act on two different bodies. This explains how systems like walking, swimming, and rocket propulsion work. The concepts are often illustrated with practical examples like the recoil of a gun and forces on interacting blocks, solidifying the idea that forces always occur in pairs.

Exercise 3 (A)

Question 1.

(a) Explain giving two examples of following : Contact forces

(b) Explain giving two examples of following : Non – contact forces

Ans:

(a) Contact Forces

Contact forces are those forces that arise only when two interacting objects are physically touching each other.

- Frictional Force (or Friction): This force always opposes motion when one surface slides or tends to slide over another. It acts tangentially along the surfaces in contact.

- Example 1: When you push a book across a table, the opposing force that slows the book down is friction between the book’s cover and the tabletop.

- Example 2: The force applied by brakes on a bicycle wheel to stop it is a frictional force.

- Normal Reaction Force: This is the perpendicular push exerted by a surface on an object resting on it. It prevents the object from falling through the surface.

- Example 1: A book resting on a shelf exerts a downward gravitational force, and the shelf exerts an equal and opposite upward normal force on the book.

- Example 2: The upward force of a floor supporting a person standing on it.

(b) Non-Contact Forces (Field Forces)

Non-contact forces are those forces that act on an object without any physical contact between the interacting bodies. These forces act through the space surrounding the object, often referred to as a field.

- Gravitational Force: This is the force of attraction that exists between any two masses. Its strength depends on the mass of the objects and the distance between them.

- Example 1: A ball thrown up falls back down to Earth due to the gravitational pull.

- Example 2: The Earth revolving around the Sun is held in its orbit by the Sun’s gravitational force.

- Magnetic Force: This is the force exerted by magnets on other magnets or on ferromagnetic materials like iron.

- Example 1: A magnet attracting a nail from a short distance without touching it.

- Example 2: The force of repulsion between the two poles (North-North or South-South) of two separate magnets.

Question 2.

Classify the following amongst contact and non – contact forces:

Frictional force

Normal reaction force

Force of tension in a string

Gravitational force

Electrostatic force

Magnetic force

Ans:

| Force | Classification | Explanation |

| Frictional force | Contact | Arises from the direct physical interaction (rubbing) between two surfaces. |

| Normal reaction force | Contact | Is the supporting force exerted by a surface perpendicular to the object touching it. |

| Force of tension in a string | Contact | Is the pulling force transmitted through a string, rope, or cable, requiring physical connection. |

| Gravitational force | Non-Contact | Acts remotely through a field, attracting any two objects with mass. |

| Electrostatic force | Non-Contact | Acts remotely between two charged particles or objects. |

| Magnetic force | Non-Contact | Acts remotely through a field, exerted by magnets on magnetic materials or moving charges. |

Question 3.

Give one example in each case where :

The force is of contact, and Force is at a distance

Ans:

| Type of Force | Example | Explanation |

| Contact Force | Pushing a shopping cart | The force you apply requires direct physical contact with the cart to initiate or change its motion. |

| Non-Contact Force | A magnet pulling an iron nail | The magnetic force acts through the surrounding space (a field) to attract the nail without touching it. |

Question 4.

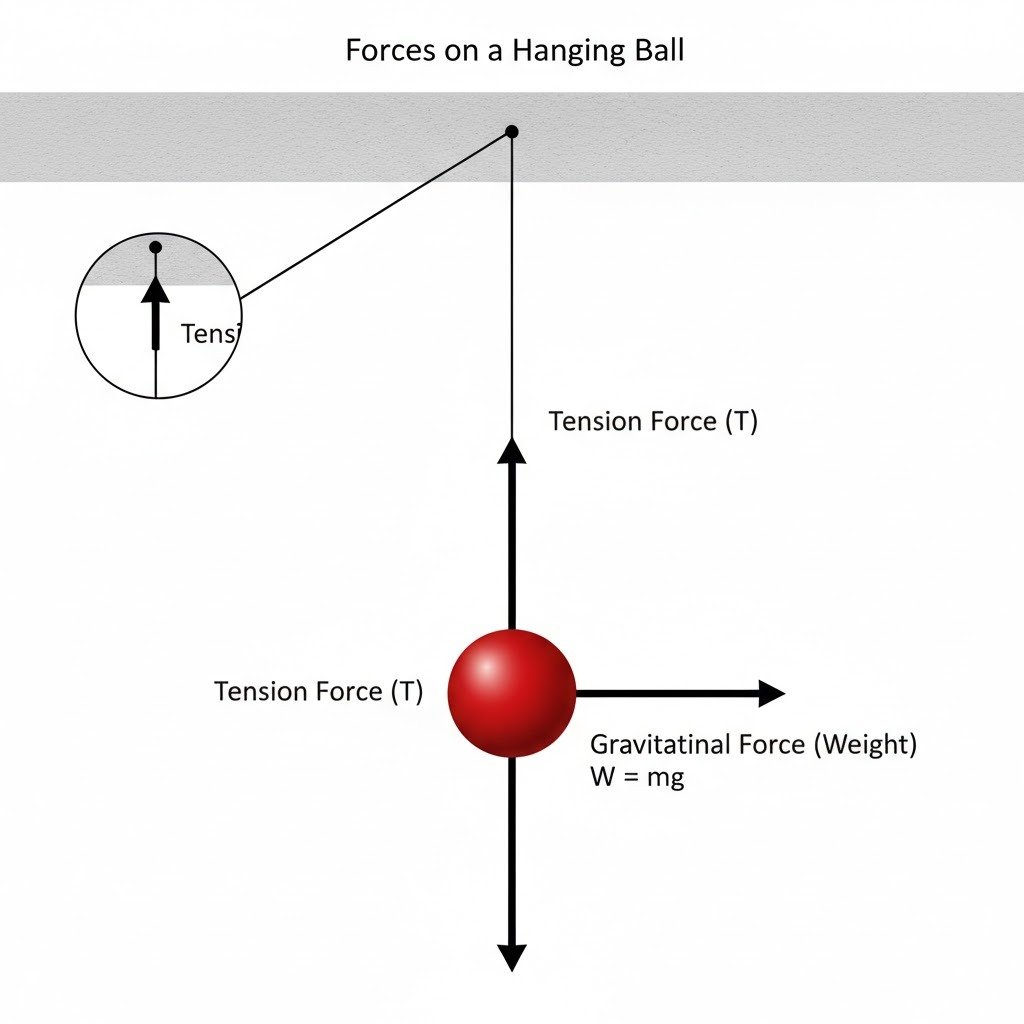

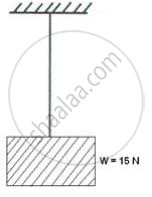

(a) A ball is hanging by string from the ceiling of the roof. Draw a neat labelled diagram showing the forces acting on the ball and the string.

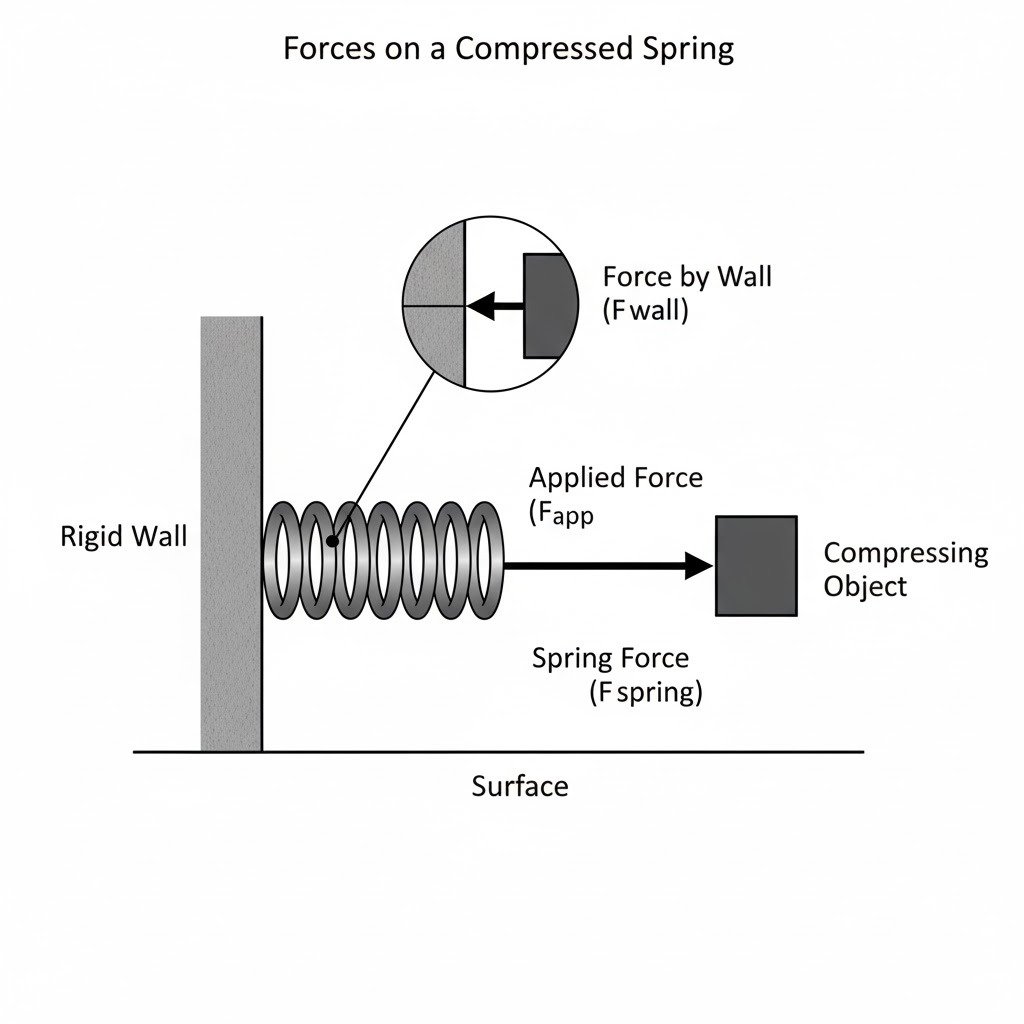

(b) A spring is compressed against a rigid wall. Draw a neat and labeled diagram showing the forces acting on the spring.

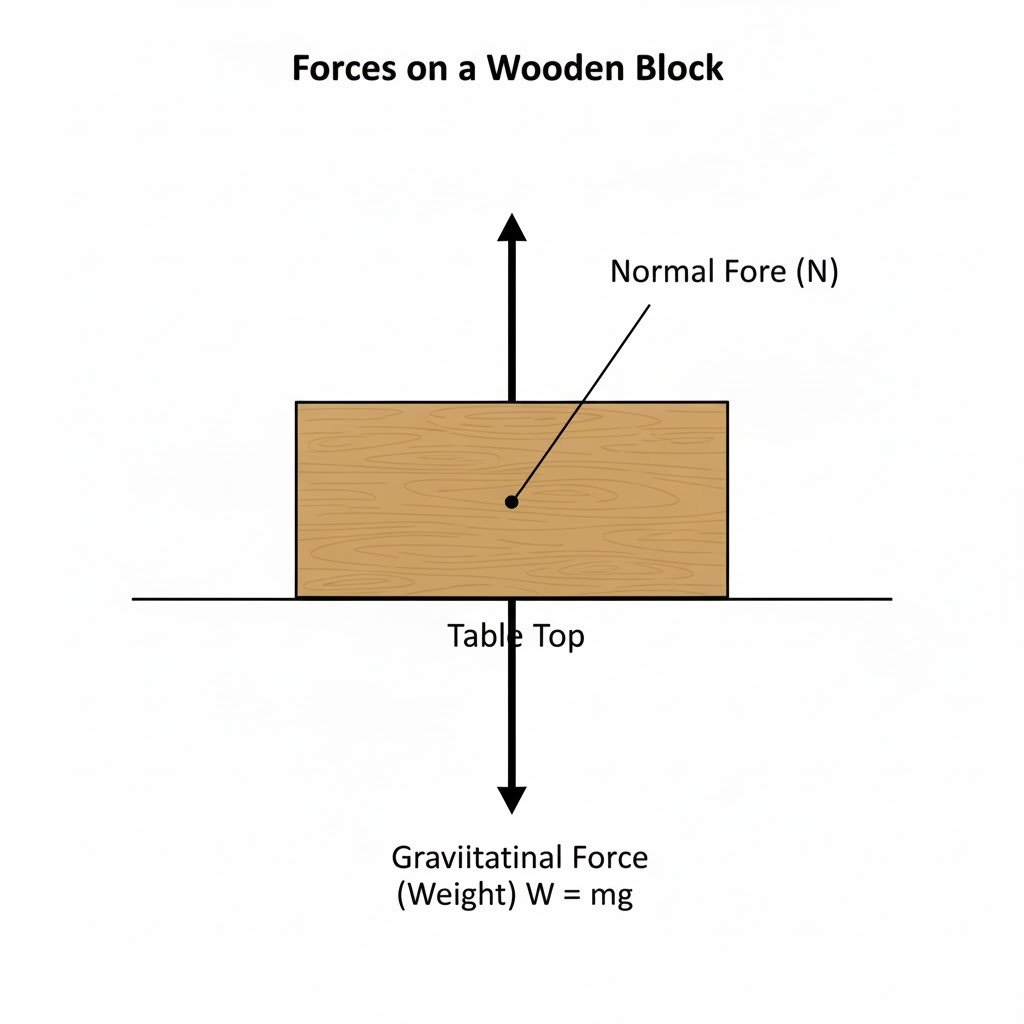

(c) A wooden block is placed on a table top. Name the forces acting on the block and draw a neat and labelled diagram to show the point of application and direction of these forces.

Ans:

(a)

Here’s the diagram showing the forces acting on the ball:

The forces acting on the ball are:

- Gravitational Force (Weight – W): Acts downwards, originating from the center of mass of the ball.

- Tension Force (T): Acts upwards along the string, exerted by the string on the ball.

(b) Spring compressed against a rigid wall:

Here’s the diagram illustrating the forces acting on the spring:

The forces acting on the spring are:

- Applied Force (F_app): The force compressing the spring from one end (e.g., from your hand or another object). This acts into the spring.

- Force by Wall (F_wall): The force exerted by the rigid wall on the spring, pushing it outwards (Newton’s third law to the spring’s push on the wall). This acts out of the spring, opposite to the direction of compression.

- Spring Force (F_spring): The internal restorative force of the spring itself, acting to return it to its original length. When compressed, this force acts outwards from both ends.

(c) Wooden block on a table top:

The forces acting on the block are:

- Gravitational Force (Weight): The force exerted by the Earth on the block, pulling it downwards.

- Normal Force: The force exerted by the table top on the block, perpendicular to the surface and pushing upwards.

Here’s the diagram showing the point of application and direction of these forces:

Question 5.

State one factor on which the magnitude of a non-contact force depends. How does it depend on the factor stated by you?

Ans:

Factor: The separation distance between the objects.

Dependence: The strength of the force weakens as the distance between the objects grows larger.

Explanation:

This inverse relationship is a fundamental principle for forces like gravity and electromagnetism. A more precise way to state it is that the force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance separating the objects. This is often called the inverse-square law.

In simpler terms, if you change the distance, the force changes by the square of that change.

Mathematical relationship: Force F ∝ 1d 2, where d is the distance. Practical example: Imagine the force between two magnets. When they are very close, the pull is strong. If you move them to three times their original separation, the force isn’t just three times weaker; it becomes nine times weaker (because32=9 ).

Question 6.

The separation between two masses is reduced to half. How is the magnitude of gravitational force between them affected?

Ans:

The nature of this dependence is that the force weakens as the distance increases. For fundamental forces like gravity and electromagnetism, this relationship is precisely defined by an inverse-square law. This means the strength of the force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the objects’ centers.

To illustrate, consider the gravitational force between two masses. If the separation between them is halved, the force does not merely double; it becomes four times stronger. This quadrupling occurs because the value of the distance in the denominator is squared. Halving the distance means the denominator becomes one-fourth of its original value, which results in the overall force value being multiplied by four.

Question 7.

State the effects of a force applied on A non-rigid, and A rigid body.

How does the effect of the force differ in the two cases?

Ans:

The application of a force produces different effects depending on whether the body is rigid or non-rigid.

Effects of a Force

1. On a Rigid Body

A rigid body is an idealized body where the distance between any two of its particles remains constant regardless of the force applied.

The effects of a force on a rigid body are limited to changing its state of motion:

- Change in Motion (Translation): The force can start motion in a stationary body, stop a moving body, or change the speed or direction of a moving body.

- Change in Orientation (Rotation): If the force is applied away from the center of mass (or center of rotation), it can cause the body to rotate or turn (known as the moment of force or torque).

- No Deformation: The force cannot change the size or shape of an ideal rigid body.

2. On a Non-Rigid Body

A non-rigid body (or deformable body) can change its inter-particle spacing and, therefore, its shape and size when a force is applied.

The effects of a force on a non-rigid body include both changes in motion and changes in form:

- Change in Motion (Translation/Rotation): Similar to a rigid body, the force can change the state of rest or motion (speed, direction, or rotation) of the body.

- Change in Form (Deformation): The force can change the size, shape, or volume of the body. This is the characteristic effect that defines a non-rigid body (e.g., compressing a sponge or stretching a rubber band).

How the Effect of the Force Differs

The primary difference in the effect of a force on the two types of bodies is the occurrence of deformation:

| Feature | Rigid Body (e.g., a solid steel block) | Non-Rigid Body (e.g., a clay ball) |

| Motion | Force causes change in motion (translation or rotation). | Force causes change in motion (translation or rotation). |

| Form/Shape | Force does NOT cause deformation (no change in shape or size). | Force DOES cause deformation (change in shape or size). |

| Summary | Force only produces external effects (changes in motion). | Force produces both external effects (motion) and internal effects (deformation). |

The key takeaway is that an applied force will always cause deformation in a non-rigid body along with any possible motion, whereas it will only cause motion (translation or rotation) in a rigid body.

Question 8.

Give one example in each of the following cases where a force:

(i) Stops a moving body.

(ii) Moves a stationary body.

(iii) Changes the size of a body.

(iv) Changes the shape of a body.

Ans:

| Case | Example |

| (i) Stops a moving body. | A fielder in a cricket match applies a force with their hands to stop a moving ball. |

| (ii) Moves a stationary body. | Kicking a stationary football applies a force that causes it to move. |

| (iii) Changes the size of a body. | Pushing the plunger of a syringe filled with air or water applies a force that compresses the contents, thereby changing the volume (size) of the trapped fluid/gas. |

| (iv) Changes the shape of a body. | Squeezing a piece of soft clay applies a force that changes its shape. (e.g., molding clay). |

Exercise 3 (A)

Question 1.

Which of the following is a contact force:

- Electrostatic force

- Gravitational force

- Frictional force

- Magnetic force

Question 2.

The non – contact force is :

- Force of reaction

- Force due to gravity

- Tension in string

- Force of friction

Exercise 3 (B)

Question 1.

Name the physical quantity that causes motion in a body.

Ans:

The physical quantity responsible for initiating or altering the state of motion of a body is Force.

Specifically, a net external force (or unbalanced force) is the agent that produces a change in motion. The effects of this force are described by the following:

- Starting Motion: A body at rest requires an unbalanced force to begin moving.

- Changing Speed: A moving body will speed up or slow down if an unbalanced force acts upon it along the direction of motion.

- Changing Direction: A moving body requires an unbalanced force to change the direction of its motion.

As established by Newton’s Second Law of Motion, the net force Facting on an object is directly proportional to the rate of change of its linear momentum.For an object with constant mass m, this relationship simplifies to:

F= ma

Here, a represents the acceleration of the body.Since acceleration is the rate at which velocity changes, force is fundamentally the cause of any change in the velocity (magnitude or direction) of an object.

Question 2.

Is force needed to keep a moving body in motion?

Ans:

This is the central concept of Newton’s First Law of Motion, often called the Law of Inertia.

Explanation

- Inertia: A body’s natural tendency (or inertia) is to maintain its current state of motion. If it’s at rest, it stays at rest; if it’s moving, it continues to move at a constant velocity (constant speed and constant direction).

- Net Force is Zero: According to the First Law, a body moving with a constant velocity has a net external force of zero acting upon it. The net force is the vector sum of all forces.

- Force Causes Change: Force is only required to change the state of motion—to accelerate the body (speed up, slow down, or change direction).

Everyday Observation vs. Physics

In daily life, it seems like a continuous force is needed (e.g., you must keep pedaling a bicycle or running a car engine). However, this is because of opposing forces like:

- Friction: The force between surfaces (like tires on the road).

- Air Resistance (Drag): The force from air molecules.

To maintain a constant velocity on Earth, you must apply a force equal and opposite to these opposing forces. This applied force simply balances the friction and drag, resulting in a net force of zero, which then allows the object to move without acceleration (i.e., at a constant velocity). If you were in the vacuum of deep space, a single initial push would be enough to keep a body moving forever without any additional force.

Question 3.

A ball moving on a table top eventually stops. Explain the reason .

Ans:

The fundamental reason a moving ball on a tabletop eventually stops is the presence of unbalanced external forces that oppose its motion, overcoming its inertia.

According to Newton’s First Law of Motion (the Law of Inertia), an object in motion will remain in motion with a constant velocity unless acted upon by a net external force. Since the ball’s velocity changes (it slows down and stops), a net retarding force must be at work.

The primary forces responsible for stopping the ball are:

1. Force of Friction (Rolling Resistance)

This is the main reason the ball slows down and stops.

- Mechanism: Friction acts between the surface of the ball and the surface of the tabletop.

- Energy Conversion: This force causes the kinetic energy (energy of motion) of the ball to be continuously converted into thermal energy (heat) and some sound energy, leading to a decrease in the ball’s speed until all the initial kinetic energy is dissipated and the ball comes to rest.

- Rolling Resistance: The friction that resists rolling motion arises largely from the slight, unavoidable deformation of the ball and the surface at the point of contact. This deformation creates a resistive torque that opposes the rolling motion.

2. Air Resistance (Drag)

This is a secondary force that also contributes to slowing the ball down.

- Mechanism: The ball has to push through the air (or any surrounding fluid medium) as it moves. The air molecules exert a force, called drag, on the ball in the direction opposite to its motion.

- Magnitude: While always present, this effect is typically much smaller than the friction between the ball and the table, especially at low speeds.

Question 4.

A ball is moving on a perfectly smooth horizontal surface. If no force is applied on it, then will its speed decrease, increase or remain unchanged?

Ans:

Here is the explanation:

- Perfectly Smooth Horizontal Surface: This means there is no frictional force acting horizontally on the ball. Frictional force is typically the main force that opposes motion and causes a moving object to slow down (decrease its speed).

- No Force is Applied: This means the net external force Fnet acting on the ball is zero. While gravity acts downward and the normal force from the surface acts upward, these forces are balanced and cancel each other out, leaving a zero net force in both the vertical and horizontal directions.

- Newton’s First Law: This law states that an object in motion will remain in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force.

Since Fnet = 0, the ball has zero acceleration a= Fnet m = 0

Therefore, the ball will continue to move at a constant velocity (constant speed and constant direction), and its speed will remain unchanged.

Question 5.

What is Galileo’s law of inertia?

Ans:

Galileo’s law of inertia is a fundamental principle in classical mechanics that describes the natural tendency of an object to resist changes in its state of motion. It served as the crucial conceptual foundation for what later became Isaac Newton’s First Law of Motion.

Galileo’s law states that:

A body moving on a perfectly level surface will continue in the same direction at a constant speed unless it is disturbed by an external force.

Context and Explanation

Prior to Galileo, the prevailing Aristotelian view held that an external force was required to maintain motion. Galileo challenged this by reasoning based on his experiments with inclined planes:

- Inclined Plane Experiment: Galileo observed that a ball rolling down an incline and up a second incline would reach nearly the same height, regardless of the angle of the second incline (neglecting friction).

- Ideal Horizontal Plane: He then reasoned that if the second incline were made perfectly horizontal (a “level surface”) and there were absolutely no friction or air resistance, the ball would never reach the original height and, therefore, would have to continue rolling indefinitely at a constant velocity.

This thought experiment led him to conclude that a force is not necessary to keep a body moving, but rather is necessary only to change its state of motion (i.e., to start it, stop it, or change its direction). This tendency of a body to maintain its state of rest or uniform motion is called inertia.

The concept of inertia established by Galileo is often summarized in the following two parts, which are essentially the statements of Newton’s First Law:

- An object at rest will remain at rest.

- An object in uniform motion (constant speed in a straight line) will remain in uniform motion.

- …unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force.

Question 6.

State Newton’s first law of motion.

Ans:

Newton’s first law of motion, the Law of Inertia, fundamentally describes the natural tendency of an object to resist changes to its motion.

Here is a unique restatement of the law:

An object possesses an inherent characteristic, called inertia, that dictates its behavior in the absence of external influence: Any mass maintains its state of zero motion (rest) or constant, straight-line velocity unless an unbalanced force is imposed upon it.

Key Implications

The essence of this law can be broken down into two distinct scenarios:

- Objects at Rest: To move a stationary object, a net force is absolutely required to overcome its inertia of rest. In the absence of such a push or pull, the object remains perpetually immobile.

- Objects in Motion: A moving object, once set into uniform motion (steady speed in an unwavering direction), requires a net force to slow it down, speed it up, or curve its path. Without external forces like friction or air resistance, the object would continue its journey at that same constant velocity indefinitely.

Question 7.

State and explain the law of inertia (or Newton’s first law of motion).

Ans:

The Law of Inertia is also known as Newton’s First Law of Motion.

Here is the statement and a brief explanation:

Statement of the Law of Inertia

A body at rest will remain at rest, and a body in uniform motion will remain in uniform motion along a straight line, unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force.

Explanation of the Law

This law essentially defines the property of inertia, which is the natural tendency of an object to resist changes in its state of motion.

- If the Net Force is Zero: If a body has no net external force acting on it , it will maintain its current velocity:

- If velocity v is zero (at rest), it stays at rest.

- If velocity v is constant (uniform motion), it continues at that constant velocity.

- To Change Motion: A force is required only to change the state of motion (i.e., to cause acceleration). In the absence of force (like gravity, friction, air resistance, etc.), an object would simply continue moving forever in a straight line at a constant speed.

Question 8.

What is meant by the term inertia?

Ans:

The term inertia refers to the inherent property of an object to resist changes in its state of motion (or state of rest).

In simpler terms:

- If an object is at rest, inertia is its tendency to stay at rest.

- If an object is in motion, inertia is its tendency to keep moving at the same velocity (same speed and same direction).

The mass of an object is the quantitative measure of its inertia: the greater the mass, the greater the inertia.

Question 9.

Give a qualitative definition of force on the basis of Newton’s first law of motion.

Ans:

Based on Newton’s first law of motion, force is defined as a push or a pull that is necessary to change the state of motion or state of rest of a body.

In other words, since an object maintains its state of uniform motion or rest unless acted upon by an external agent, a force is that external influence or cause which is required to initiate a change in its velocity (i.e., cause acceleration).

Question 10.

Name the factor on which the inertia of a body depends and state how it depends on the factor stated by you .

Ans:

The factor on which the inertia of a body depends is its mass m.

It depends on the mass in a directly proportional manner:

- How it depends: The greater the mass of a body, the greater its inertia.

- Conversely: The smaller the mass of a body, the smaller its inertia.

Inertia is fundamentally the measure of a body’s resistance to any change in its state of motion (i.e., its resistance to acceleration), and mass is the quantitative measure of this inertia.

Question 11.

Give two examples to show that greater the mass, greater is the inertia of the body.

Ans:

Inertia is a body’s natural tendency to resist any change in its state of motion. Mass is the quantitative measure of that inertia. Therefore, a greater mass implies a greater resistance to a change in motion.

Here are two examples demonstrating this relationship:

1. Pushing a Vehicle vs. Pushing a Bicycle

- Scenario: Imagine attempting to push a parked truck (high mass) and a parked bicycle (low mass) from a state of rest.

- Observation: You must exert a significantly greater force to get the heavy truck moving compared to the bicycle.

- Conclusion: The truck’s greater mass gives it greater inertia (greater resistance to starting motion), requiring a larger force to change its state of rest.

2. Catching a Stone vs. Catching a Rubber Ball

- Scenario: Consider a stone and a rubber ball of the same size, both thrown at the same speed. You attempt to catch both.

- Observation: The stone (higher density, therefore higher mass) is much harder to stop than the rubber ball (lower mass), and it exerts a greater impact force on your hands.

- Conclusion: The stone’s greater mass gives it greater inertia (greater resistance to stopping motion), requiring a larger force over a given time to bring it to rest.

Question 12.

‘More the mass, the more difficult it is to move the body from rest’. Explain this statement by giving an example.

Ans:

The statement “More the mass, the more difficult it is to move the body from rest” is a straightforward description of a physical property called inertia.

Explanation based on Inertia

Inertia is the inherent property of a body that resists any change in its state of rest or motion. Mass is the quantitative measure of a body’s inertia.

- Higher Mass Greater Inertia: A body with greater mass possesses greater inertia. This means it has a stronger tendency to remain at rest (if stationary) or to continue moving (if in motion).

- Difficulty in Motion: To overcome this greater inertia and change the body’s state from rest to motion, a larger force must be applied, making it “more difficult” to move.

Example

Consider trying to push two stationary objects:

- A small, empty cardboard box with low mass.

- A large, fully loaded truck of high mass.

You can easily set the cardboard box into motion with a gentle tap (small force). However, getting the large, loaded truck to even budge requires a significantly greater force.

This is because the loaded truck has far greater mass and thus greater inertia, offering much more resistance to the change in its state of rest compared to the light cardboard box.

Question 13.

Name the two kinds of inertia.

Ans:

The two kinds of inertia are:

- Inertia of Rest

- Inertia of Motion

Question 14.

Give one example of each of the following :

(a) inertia of rest, and (b) inertia of motion .

Ans:

Examples of Inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of an object to resist a change in its state of motion.

(a) Inertia of Rest

This is the tendency of a body to remain at rest and resist being set into motion.

- Example: When a stationary bus suddenly starts moving, passengers standing inside tend to fall backwards. This happens because their feet (in contact with the bus floor) move forward, but their upper body resists this change due to inertia and tries to stay in its original state of rest.

(b) Inertia of Motion

This is the tendency of a body to remain in uniform motion (constant speed and direction) and resist being stopped or slowed down.

- Example: When a fast-moving car or bus suddenly applies brakes, the passengers tend to fall forward. This is because the lower part of their body stops with the vehicle, but their upper body continues to move forward due to its inertia of motion.

Question 15.

Two equal and opposite forces act on a stationary body. Will the body move? Give a reason to your answer.

Ans:

No, the body will not move.

Reason

When two equal and opposite forces act on a stationary body, they constitute a balanced pair of forces.

- Net Force is Zero: The forces cancel each other out, resulting in a net force (resultant force) of zero.

- Newton’s First Law: According to Newton’s First Law of Motion (the Law of Inertia), a stationary body remains at rest unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force.

Question 16.

Two equal and opposite forces act on a moving object. How is its motion affected? Give a reason.

Ans:

The motion of the object is unaffected; it will continue to move at a constant velocity (same speed and same direction).

Reason

The two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction, meaning they are balanced forces.

When forces are balanced, the net force (Fnet) acting on the object is zero (Fnet = 0).

According to Newton’s First Law of Motion (The Law of Inertia), an object in motion will continue in motion with a constant velocity unless acted upon by a nonzero net force. Since the net force is zero, the object’s velocity (speed and direction) will not change.

Question 17.

An airplane is moving uniformly at a constant height under the action of two forces (i) Upward force (lift) and (ii) Downward force (weight). What is the net force on the aeroplane?

Ans:

The aeroplane is moving uniformly (constant velocity) at a constant height.

According to Newton’s First Law of Motion, a body continues in its state of rest or uniform motion unless acted upon by a net external force. Since the velocity (speed and direction) of the aeroplane is constant (uniform motion), its acceleration is zero.

The condition for zero acceleration is that the net force acting on the body must be zero.

Since the aeroplane is moving at a constant height, it is in vertical equilibrium. This means the upward force (lift) and the downward force (weight) must be equal in magnitude.

Lift – Weight = 0

Therefore, the net force on the aeroplane is zero.

Question 18.

Why does a person fall when he jumps out from a moving train ?

Ans:

This phenomenon is best explained by Newton’s First Law of Motion, often called the Law of Inertia.

Here is the explanation:

Why a Person Falls

When a person is inside a moving train, their entire body (including internal organs and clothes) is moving forward at the same high velocity as the train.

- Initial State (Inertia of Motion): When the person jumps out, their body retains the inertia of motion and continues to move forward at the train’s high speed.

- Contact with Ground (Sudden Change): The moment the person’s feet touch the stationary ground, the friction between their shoes and the ground exerts a large, sudden backward force on their feet. This force rapidly brings the feet to rest.

- Upper Body Continues: Since there is no such immediate stopping force on the upper body, the upper body continues to move forward due to inertia.

- Result: The feet stop abruptly, but the upper body continues forward, causing the person to lose balance and fall forward in the direction the train was moving.

Question 19.

Why does a coin, placed on a card, drop into the tumbler when the card is rapidly flicked with a finger?

Ans:

The coin drops into the tumbler because of inertia of rest.

- Inertia of Rest: The coin is initially at rest and, due to its inertia, it tends to remain at rest.

- Force on the Card: When the card is rapidly flicked, a large external force acts only on the card, causing it to accelerate quickly and move out from under the coin.

- No Force on the Coin: Since the flicking force was not applied to the coin, and the flick was rapid (minimizing friction), the coin does not acquire enough horizontal velocity to move with the card.

- Gravity Takes Over: With the support (the card) suddenly removed, gravity becomes the dominant force acting on the coin, causing it to fall straight down into the tumbler.

Question 20.

Why does a ball thrown vertically upwards in a moving train , come back to the thrower’s hand ?

Ans:

The ball returns to the thrower’s hand because of inertia, specifically the shared horizontal velocity between the ball, the thrower, and the train.

Here is a short, unique explanation:

The moment the ball leaves the thrower’s hand, it possesses two key components of velocity:

- Vertical Velocity: Given by the thrower (upwards).

- Horizontal Velocity: Inherited from the moving train.

While the ball is in the air, the only force acting on it horizontally is air resistance (which is negligible for a short throw). Therefore, due to Newton’s First Law (Inertia), the ball continues to move forward horizontally at the same speed as the train and the thrower.

The thrower, the ball, and the train all travel the same horizontal distance during the time the ball is in the air, ensuring the ball lands precisely back in the thrower’s hand.

Question 21.

(a) Explain the following : When a train suddenly moves forward , the passenger standing in the compartment tends to fall backwards .

(b) Explain the following : When a corridor train suddenly starts , the sliding doors of some compartments may open.

(c) Explain the following:People often shake the branches of a tree to get its fruits down.

(d) Explain the following :After alighting from a moving bus , one has to run for some distance in the direction of the bus in order to avoid falling .

(e) Dust particles are removed from a carpet by beating it.

(f) Explain the following : It is advantageous to run before taking a long jump .

Ans:

These phenomena are all explained by the concept of Inertia, which is a body’s resistance to a change in its state of rest or motion.

(a) Passenger Tends to Fall Backwards

When a train suddenly moves forward, the lower part of the passenger’s body (feet) moves forward immediately with the train. However, the upper part of the body tends to remain in its state of rest due to inertia of rest. This lag causes the upper body to momentarily stay behind, making the passenger fall backward relative to the moving train.

(b) Sliding Doors Open When a Train Starts

When a stationary corridor train suddenly starts, the sliding doors, which are relatively loose, tend to remain in their state of rest due to inertia of rest. The body of the compartment moves forward, but the doors momentarily stay put. If the force of the push by the door frame on the door is not strong enough to overcome the door’s inertia, the door slides open backward relative to the train.

(c) Shaking Branches to Get Fruits Down

The fruits and the branches are initially at rest. When the branch is suddenly shaken, the branch moves, but the fruits tend to remain in their state of rest due to inertia of rest. The sudden movement breaks the weak connection (stem) between the fruit and the branch, causing the fruit to fall due to gravity.

(d) Running After Alighting from a Moving Bus

Before alighting, the passenger’s entire body is moving forward with the bus, possessing inertia of motion. When the feet touch the ground, they stop or slow down suddenly. However, the upper body tends to continue moving forward at the bus’s speed due to inertia of motion. To prevent the upper body from being thrown forward and causing a fall, one must run forward for a short distance to gradually reduce the forward momentum of the entire body.

(e) Dust Particles are Removed from a Carpet

When a carpet is beaten with a stick, the carpet is suddenly set into motion. The dust particles resting on the carpet, however, tend to remain in their state of rest due to inertia of rest. This sudden separation (carpet moves, dust stays) causes the dust to be dislodged and fall off due to gravity.

(f) Running Before Taking a Long Jump

It is advantageous to run before a long jump to build up inertia of motion (momentum). The forward momentum gained from running helps the jumper cover a greater horizontal distance during the jump. This built-up force of inertia allows the jumper’s body to carry on in the air for a longer duration and distance than if they jumped from a stationary position.

Exercise 3 (B)

Question 1.

The property of inertia is more in :

- a car

- a truck

- a horse cart

- a toy car

Question 2.

A tennis ball and a cricket ball , both are stationary. To start motion in them .

- less force is required for the cricket ball than for the tennis ball .

- a less force is required for the tennis ball than for the cricket ball

- The same force is required for both the balls .

- nothing can be said .

Question 3.

A force is needed to :

- Change the state of motion or state of rest of the body .

- Keep the body in motion

- keep the body stationary

- keep the velocity of the body constant .

Exercise 3 (C)

Question 1.

Name the two factors on which the force needed to stop a moving body in a given time depends.

Ans:

The two factors on which the force needed to stop a moving body in a given time depends are:

- Mass (m) of the body.

- Velocity (v) of the body (specifically, the change in velocity required,Δv).

This dependence is derived from the concepts of momentum and the impulse-momentum theorem:

- Momentum (p): Momentum is the product of mass and velocity (p = mv). The greater the initial momentum of the body, the greater the force required to stop it in a fixed time.

- Impulse-Momentum Theorem: Force (F) multiplied by the time interval (Δt) equals the change in momentum (Δp):F Since the time (Δt) is fixed, the required force is directly proportional to the change in momentum:

To stop a body, the change in momentum (Δp) is essentially equal to its initial momentum (mΔv). Therefore, F depends on both the mass (m) and the change in velocity (Δv).

Question 2.

Define linear momentum and state its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Here is the definition and unit for linear momentum.

Linear Momentum is defined as the product of the mass and the velocity of a moving object. It is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction. The direction of the linear momentum is the same as the direction of the object’s velocity.

S.I. Unit: kilogram metre per second (kg m/s).

Question 3.

A body of mass m moving with a velocity v is acted upon by a force. Write an expression for change in momentum in each of the following cases: (i) When v << c, (ii) When v → c and (iii) When v << c but m does not remain constant. Here, c is the speed of light.

Ans:

The change in momentum (Δp) is calculated as the final momentum (p₂) minus the initial momentum (p₁). The expression for momentum itself depends on the physical context, particularly the object’s velocity and mass.

Here are the expressions for the change in momentum in each case:

(i) When v << c (Classical/Newtonian Mechanics)

At speeds very small compared to light, mass is considered constant (invariant). Momentum is defined as p = mv.

- Expression for Change in Momentum:

Δp = p₂ – p₁ = mv₂ – mv₁ = m(v₂ – v₁)

This can also be written as Δp = mΔv, where Δv is the change in velocity.

(ii) When v → c (Relativistic Mechanics)

As velocity approaches the speed of light, relativistic effects dominate. Mass is no longer constant and increases with velocity. The relativistic momentum is p = γm₀v, where:

- m₀ is the rest mass.

- γ (gamma) is the Lorentz factor, given by γ = 1 / √(1 – v²/c²).

- Expression for Change in Momentum:

Δp = p₂ – p₁ = γ₂m₀v₂ – γ₁m₀v₁ = m₀(γ₂v₂ – γ₁v₁)

This expression accounts for the changes in both velocity and the relativistic gamma factor.

(iii) When v << c but m does not remain constant (Variable Mass System)

This case applies to systems like rockets or conveyors where the object’s mass changes, even at low speeds. The classical form p = mv still applies, but now mass (m) is a function of time, m(t).

- Expression for Change in Momentum:

The momentum is p(t) = m(t)v(t). The change in momentum is found using the product rule of calculus.

Δp = p₂ – p₁ = m₂v₂ – m₁v₁

For an infinitesimal change, the rate of change of momentum is dp/dt = (d(mv))/dt = v(dm/dt) + m(dv/dt).

Question 4.

Show that the rate of change of momentum = mass × acceleration. Under what condition does this relation hold?

Ans:

The derivation of Rate of change of momentum = mass × acceleration comes directly from applying the definition of momentum and the condition of constant mass.

Question 5.

Two bodies A and B of same mass are moving with velocities v and 2v, respectively. Compare their (i) inertia and (ii) momentum.

Ans:

Question 6.

Two balls A and B of masses m and 2 m are in motion with velocities 2v and v, respectively. Compare:

(i) Their inertia.

(ii) Their momentum.

(iii) The force needed to stop them at the same time.

Ans:

(i) Comparison of Inertia

Inertia is the measure of an object’s reluctance to have its state of motion altered. This property is determined exclusively by the object’s mass.

- Ball A possesses a mass of m.

- Ball B possesses a mass of 2m.

Since inertia is directly proportional to mass, Ball B, with twice the mass, has twice the inertia of Ball A. Therefore, the ratio of inertia of Ball B to Ball A is 2 : 1.

Question 7.

State Newton’s second law of motion. What information do you get from it?

Ans:

Question 8.

How does Newton’s second law of motion differ from the first law of motion?

Ans:

| Feature | Newton’s First Law (Law of Inertia) | Newton’s Second Law |

| Focus | Defines the conditions under which no change in motion occurs. | Defines the resulting change in motion (acceleration) when a net force is present. |

| Net Force (Fnet) | States that if Fnet=0, then acceleration (a) is zero, meaning velocity (v) is constant. | States that if Fnet=0, it produces acceleration (a). |

| Nature of Force | A qualitative statement. It conceptually defines what an external force is (something that changes an object’s state of motion). | A quantitative statement. It provides a way to measure the force required to cause a specific acceleration. |

| Mathematical Relation | Fnet=0⟹a=0 | Fnet=ma |

Question 9.

Write the mathematical form of Newton’s second law of motion. State the conditions if any. 10. State Newton’s second law of motion. Under what condition does it take the form F = ma?

Ans:

Newton’s Second Law of Motion: The Principle of Force and Change

Core Idea:

This law establishes a precise, measurable link between the force acting on an object and the change in its motion. It tells us that a force doesn’t just cause motion; it causes a change in motion.

Fundamental Statement:

The acceleration of an object is directly tied to the net force acting upon it and inversely tied to its mass. The resulting acceleration happens in the same direction as the net force.

The Relationship in Simple Terms:

- More Force, More Acceleration: If you push an object harder (increase the net force), its acceleration increases proportionally (assuming mass is constant).

- More Mass, Less Acceleration: If an object is heavier (has more mass), the same force will produce a smaller acceleration.

Mathematical Expression (The Common Form):

This relationship is most famously captured by the equation:

F_net = m a

Where:

- F_net is the net or unbalanced force acting on the object.

- m is the object’s mass.

- a is the acceleration that is produced.

The Deeper, More General Statement:

While F = m a is incredibly useful, it is actually a special case of a more fundamental law. The most complete statement of Newton’s Second Law deals with momentum.

Momentum (p) is defined as the product of mass and velocity (p = m v).

The law states: The net force acting on an object is equal to the rate at which its momentum changes over time.

This is written as: F_net = Δp / Δt

Where:

- Δp is the change in momentum.

- Δt is the change in time.

Connecting the Two Forms:

The equation F_net = m a is derived directly from the momentum form when the object’s mass remains constant.

Here is the step-by-step connection:

- Start with the general form: F_net = Δp / Δt

- Since momentum p = m v, a change in momentum is Δp = Δ(m v).

- If mass (m) is constant, it can be factored out: Δp = m Δv.

- Substitute back in: F_net = (m Δv) / Δt

- We know that the change in velocity over time (Δv / Δt) is the definition of acceleration (a).

- Therefore, the equation simplifies to the familiar form: F_net = m a

In Essence:

The form F_net = Δp / Δt is the universal and fundamental law. The form F_net = m a is its powerful and widely used simplification, which is valid for the vast majority of situations where an object’s mass does not change as it moves.

Question 11.

How can Newton’s first law of motion be obtained from the second law of motion?

Ans:

Newton’s second law provides the mathematical rule for how a force alters an object’s motion, stating that the net force on an object is directly proportional to the product of its mass and the acceleration it experiences (F_net = m × a).

The first law of motion can be logically deduced as a specific, foundational instance of this general rule. It describes the behavior of an object under a particular condition: when the total external force acting upon it is precisely zero.

By inserting this condition of zero net force (F_net = 0) into the equation of the second law, we get:

0 = m × a

Given that an object’s mass (m) is a positive, non-zero quantity, the only mathematical solution for this equation to hold true is for the acceleration (a) to also be zero. An acceleration of zero signifies no change in the object’s velocity. Consequently, the object must continue in its current state of motion indefinitely—whether that state is a constant velocity (which includes moving in a straight line at a steady speed) or a state of complete rest.

Thus, the first law is not an independent principle but rather the cornerstone consequence of the second law for the specific scenario where the net force is absent. It defines the natural state of motion for any object in the absence of external influences.

Question 12.

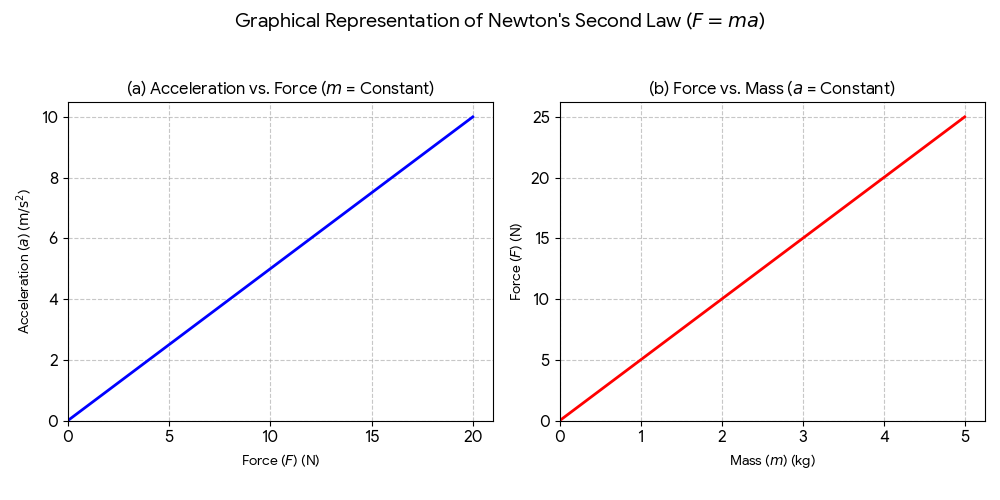

(a) Draw a graph to show the dependence of acceleration on force for a constant mass.

(b)Draw a graph to show the dependence of force on mass for a constant acceleration.

Ans:

Question 13.

How does the acceleration produced by a given force depend on the mass of the body? Draw a graph to show it.

Ans:

The Relationship Between Force, Mass, and Acceleration

The acceleration produced by a given force is inversely proportional to the mass of the body.

This means that for a constant force:

- If the mass increases, the acceleration decreases.

- If the mass decreases, the acceleration increases.

This fundamental principle is at the heart of Newton’s Second Law of Motion, which is mathematically stated as Force = Mass × Acceleration (F = m × a).

Explanation

If we rearrange the formula to solve for acceleration, we get:

a = F / m

Since the force (F) is constant, the acceleration (a) depends only on the mass (m). The equation a = F / m clearly shows that acceleration is inversely proportional to mass. For example:

- If you push a lightweight toy car and a heavy real car with the same force, the toy car will gain much more speed (higher acceleration) than the heavy car.

- A rocket’s acceleration increases as it travels and its mass decreases by burning fuel, even if the thrust (force) remains constant.

Graph of Acceleration vs. Mass (for a Constant Force)

The graph showing the relationship between acceleration and mass is a downward-sloping curve, specifically a hyperbola.

Graph Description:

The Y-axis represents Acceleration (a).

The X-axis represents Mass (m).

The curve starts high on the left (where mass is small and acceleration is high) and slopes downward to the right, getting closer and closer to the x-axis but never actually touching it.

This shape visually confirms that as mass increases, acceleration approaches zero.

Acceleration (a)

↑

| *

| *

| *

| *

| *

| *

+——————> Mass (m)

(This is a text representation of a hyperbola. In a properly drawn graph, the curve would be a smooth hyperbola.)

Key Takeaway: The graph is a visual proof of the inverse relationship. Doubling the mass halves the acceleration, tripling the mass reduces acceleration to one-third, and so on.

Question 14.

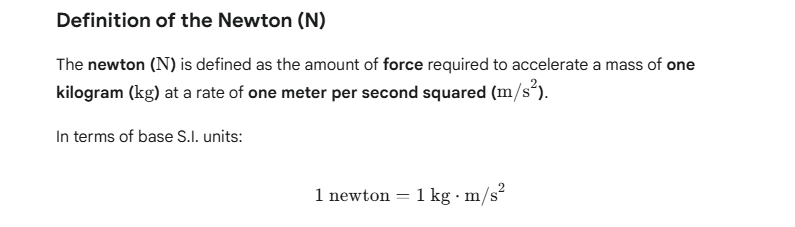

Name the S.I. unit of force and define it .

Ans:

Question 15.

What is the C.G.S. unit of force? How is it defined?

Ans:

While we commonly use the newton to quantify a push or a pull, the dyne serves as its precursor in the centimetre-gram-second (C.G.S.) system. The dyne is fundamentally defined as the intensity of force needed to impart a specific change in motion to a specific mass. To be precise, a solitary dyne of force is at work when a mass of one gram experiences an increase in its velocity of one centimetre per second with each passing second. In essence, if you were to observe a one-gram object, such as a small paper clip, and see its speed steadily rising by a single centimetre per second for every second it is pushed, the force acting upon it would be exactly one dyne. This establishes its formal equivalence to one gram-centimetre per second squared (1 g·cm/s²), making it a much smaller unit of force compared to the newton, with one newton equaling 100,000 dynes.

Question 16.

Name the S.I. and C.G.S. units of force. How are they related?

Ans:

The standardized unit for measuring force in the International System (S.I.) is the Newton, represented by the symbol N.

In the Centimeter-Gram-Second (C.G.S.) system, the corresponding unit is the Dyne, with the symbol dyn.

Connecting the Two Units

The bridge between these units is built on the definition of force itself, derived from Newton’s principle: Force is the product of mass and the acceleration it produces.

By definition:

- A 1 Newton force is the push or pull that will change the speed of a 1-kilogram object by 1 meter per second, every second.

- A 1 Dyne force is the push or pull that will change the speed of a 1-gram object by 1 centimeter per second, every second.

To find their relationship, we translate the definition of 1 Newton into the units used for the Dyne:

1 N = (1 kg) × (1 m/s²)

Now, we convert the components:

- 1 kilogram is equivalent to 1000 grams.

- 1 meter is equivalent to 100 centimeters.

Substituting these values in:

1 N = (1000 g) × (100 cm/s²)

= 100,000 g·cm/s²

Since 1 g·cm/s² is, by definition, 1 Dyne, we conclude:

1 Newton = 100,000 Dynes, which can also be written scientifically as 1 N = 10⁵ dyn.

Question 17.

Why does a glass vessel break when it falls on a hard floor, but it does not break when it falls on a carpet?

Ans:

The difference lies in how the carpet and the hard floor manage the vessel’s momentum and the duration of the impact.

When the vessel falls, it gains a certain amount of momentum (mass x velocity) by the time it hits the ground. To bring the vessel to a stop, this momentum must be reduced to zero. The key factor is the rate at which this happens, which determines the force of the impact.

- On a Hard Floor: The surface is rigid and unyielding. The vessel comes to an abrupt, almost instantaneous stop. Because the stopping time is extremely short, the deceleration is very high. A large deceleration requires a massive force (as defined by Newton’s Second Law: Force = mass x acceleration). This immense, concentrated force far exceeds the structural strength of the glass, causing it to shatter.

- On a Carpet: The carpet fibres are compressible and act like a crude cushion. Upon impact, the carpet (and its padding) compresses over a few milliseconds. This significantly increases the duration of the impact. With more time to slow down, the vessel’s deceleration is much gentler. Since the deceleration is lower, the stopping force exerted on the glass is dramatically reduced. This weaker force remains below the breaking point of the glass, allowing the vessel to survive the fall.

In essence, the carpet doesn’t change the vessel’s momentum, but it spreads the stopping force over a longer time, making it less destructive.

Question 18.

(a) Use Newton’s second law of motion to explain the following instance :

A cricketer pulls his hands back while catching a fast moving cricket ball .

(b)Use Newton’s second law of motion to explain the following instance :

An athlete prefers to land on sand instead of hard floor while taking a high jump .

Ans:

(a) A cricketer pulls his hands back while catching a fast-moving cricket ball.

Explanation using Newton’s Second Law:

Newton’s second law of motion states that the force acting on an object is equal to the rate of change of its momentum, or F = ma (where F is force, m is mass, and a is acceleration).

- The fast-moving ball has a high momentum. To catch it, the cricketer must bring its momentum to zero.

- The force experienced by the cricketer’s hands is given by F = (Change in Momentum) / Time.

- If the ball is stopped abruptly (in a very short time, t), the rate of change of momentum is very high, resulting in a large force (F). This large force would hurt the hands.

- By pulling his hands back, the cricketer increases the time duration (t) over which the ball’s momentum comes to zero.

- According to the formula, for the same change in momentum, if the time t increases, the net force F decreases.

- Therefore, by increasing the stopping time, the cricketer reduces the force exerted on his hands, preventing injury and making it easier to secure the catch.

(b) An athlete prefers to land on sand instead of a hard floor while taking a high jump.

Explanation using Newton’s Second Law:

Newton’s second law (F = ma) is again the key principle here.

- When the athlete lands after a jump, their body’s vertical velocity must be brought to zero. This means their momentum must change to zero.

- The force experienced during landing is F = (Change in Momentum) / Time.

- A hard floor is rigid and unyielding. It brings the athlete to a stop in a very short time. This results in a very high rate of change of momentum, and consequently, a large upward force (F) acts on the athlete’s body. This large force can cause injuries like fractures or severe joint pain.

- Sand, on the other hand, is soft and compressible. When the athlete lands on sand, their feet sink into it.

- This action significantly increases the time duration (t) over which the athlete’s momentum is reduced to zero.

- Since the change in momentum is the same, a longer stopping time results in a much smaller force (F) being exerted on the athlete’s body.

- This reduced force minimizes the risk of injury, making the landing safer.

Exercise 3 (C)

1. The linear momentum of a body of mass m moving with velocity v is :

- v/m

- m/v

- mv

- 1/mv

Question 2.

The unit of linear momentum is :

- N s

- kg m s-2

- N s-1

- kg2 m s-1

Question 3.

The correct form of Newton’s second law is :

- F = Δp / Δt

- F =m Δv / Δt

- F = v Δm / Δt

- F = mv

Question 4.

The acceleration produced in a body by a force of given magnitude depends on

- size of the body

- shape of the body

- mass of the body

- none of these

Exercise 3 (C)

Question 1.

A body of mass 5 kg is moving with velocity 2 m s-1. Calculate its linear momentum.

Ans:

A body of mass 5 kg is moving with a velocity of 2 m s⁻¹. The formula used to calculate linear momentum (p) is the product of its mass (m) and its velocity (v).

p=m×v

p=m×v

Substituting the provided values into the formula:

P = (5 kg) ×(2 m s−1)

p=10 kg m s−1

Therefore, the linear momentum of the body is 10 kg m s⁻¹.

Question 2.

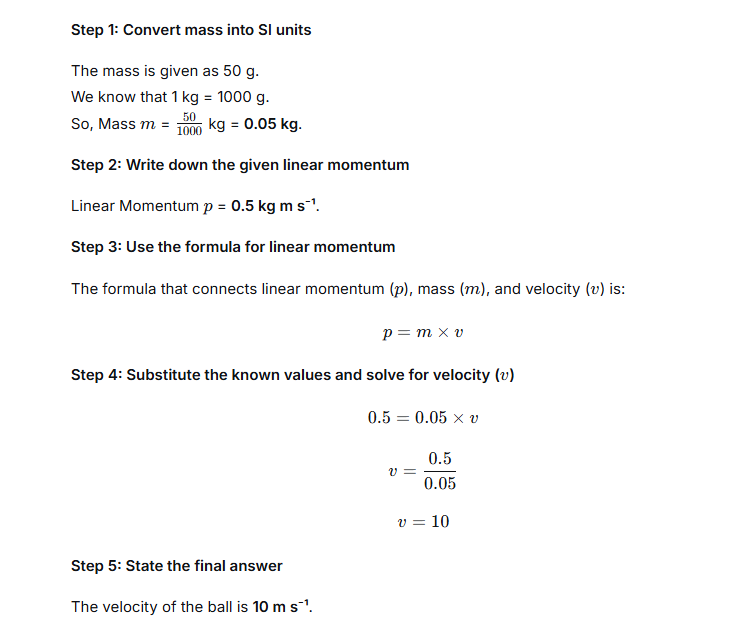

The linear momentum of a ball of mass 50 g is 0.5 kg m s-1. Find its velocity.

Ans:

Question 3.

A force of 15 N acts on a body of mass 2 kg. Calculate the acceleration produced.

Ans:

Step 1: Understand the Governing Principle

The fundamental rule of motion we apply here states that the acceleration an object experiences is a direct result of the force applied to it and is inversely related to its mass.

Step 2: List the Known Quantities

From the information provided:

- Applied Force (F) = 15 N

- Mass of the object (m) = 2 kg

Step 3: Apply the Conceptual Rule

The core relationship is that Acceleration is equal to Force divided by Mass. We express this mathematically to find our unknown.

Step 4: Perform the Calculation

Using the values:

Acceleration (a) = Force / Mass = 15 N / 2 kg

This gives the result:

a = 7.5 m/s²

Final Result:

The object will therefore accelerate at a rate of 7.5 meters per second squared.

Question 4.

A force of 10 N acts on a body of mass 5 kg. Find the acceleration produced.

Ans:

Step 1: Recall Newton’s Second Law

F = m × a

Step 2: Identify the Given Values

From the problem:

Force, F = 10 N

Mass, m = 5 kg

Step 3: Rearrange the Formula

We need to find acceleration (a). Rearranging the formula gives:

a = F / m

Step 4: Substitute the Values and Calculate

Substituting the known values into the equation:

a = 10 N / 5 kg

a = 2 N/kg

Since 1 Newton (N) is equivalent to 1 kg·m/s², the unit N/kg is the same as m/s².

a = 2 m/s²

Final Answer: The acceleration produced is 2 m/s².

Question 5.

Calculate the magnitude of force which when applied on a body of mass 0.5 kg produces an acceleration of 5 m s-2.

Ans:

To figure out how much push is required to get the object moving as described, we use the most basic law of motion. This rule simply says that the force you need is found by multiplying the object’s mass by how quickly you want it to speed up.

We can write this idea as a straightforward equation:

Force = Mass × Acceleration

From the details provided:

- The Mass of the object is 0.5 kilograms.

- The Acceleration we want it to achieve is 5 meters per second squared.

Putting these numbers into the equation looks like this:

Force = 0.5 kg × 5 m/s²

Doing the math:

0.5 times 5 equals 2.5.

When we combine the units of kilograms and meters-per-second-squared, we get the unit for force, which is the Newton.

So, the final answer is that a force of 2.5 Newtons is needed.

Question 6.

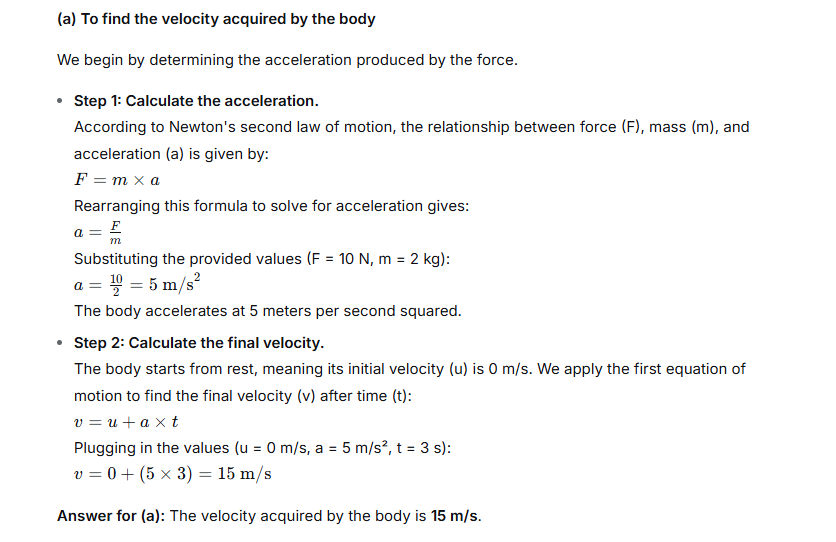

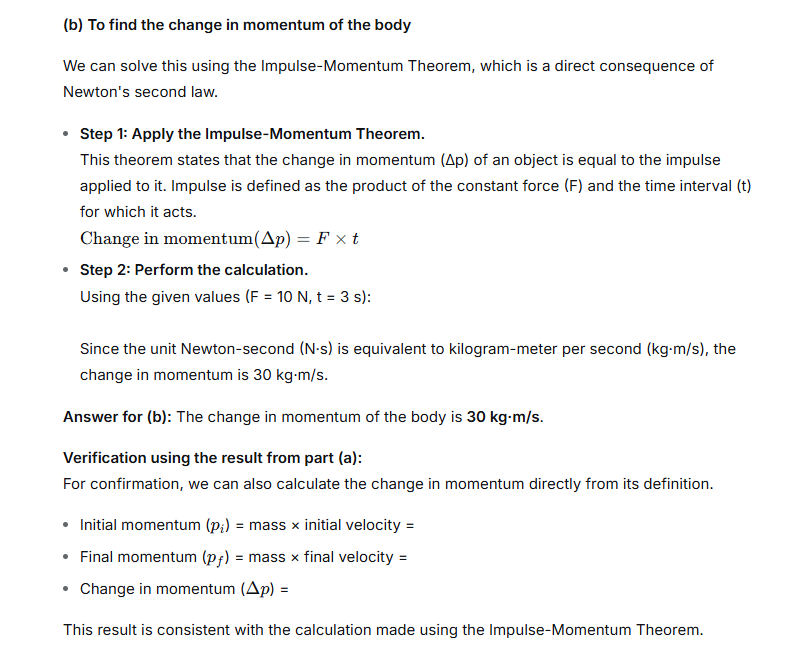

(a) A force of 10 N acts on a body of mass 2 kg for 3 s, initially at rest. Calculate : The velocity acquired by the body

(b) A force of 10 N acts on a body of mass 2 kg for 3 s, initially at rest. Calculate : Change in momentum of the body.

Ans:

Question 7.

(a) A force acts for 10 s on a stationary body of mass 100 kg, after which the force ceases to act. The body moves through a distance of 100 m in the next 5 s. Calculate: The velocity acquired by the body.

(b) A force acts for 10 s on a stationary body of mass 100 kg, after which the force ceases to act. The body moves through a distance of 100 m in the next 5 s. Calculate : The acceleration produced by the force

(c) A force acts for 10 s on a stationary body of mass 100 kg, after which the force ceases to act. The body moves through a distance of 100 m in the next 5 s. Calculate : The magnitude of the force

Ans:

Question 8.

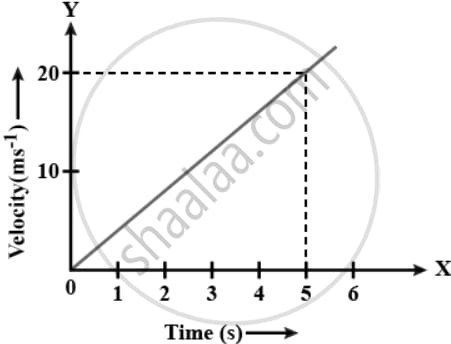

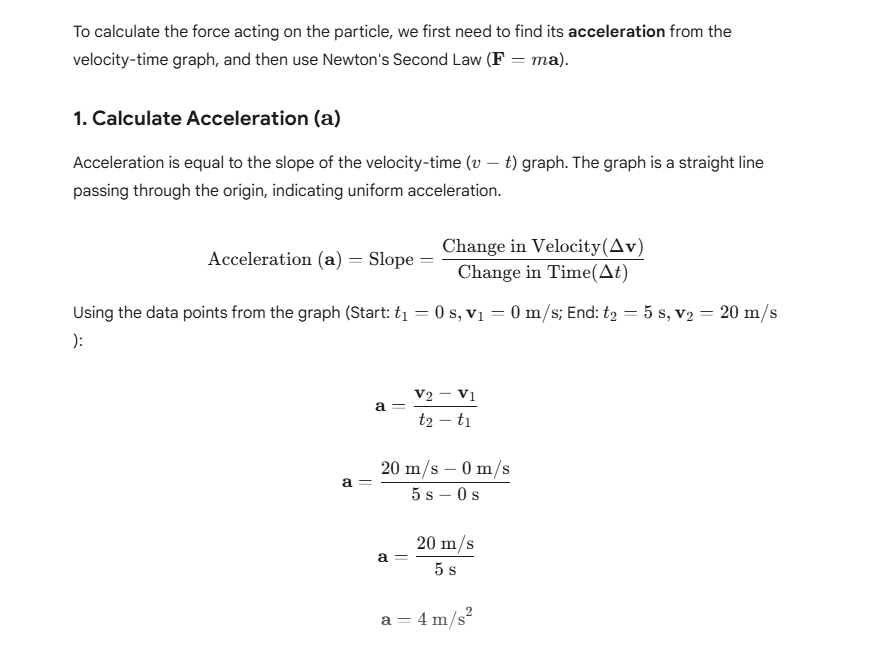

Figure shows the velocity-time graph of a particle of mass 100 g moving in a straight line. Calculate the force acting on the particle.

(Hint : Acceleration = Slope of the v-t graph)

Ans:

Question 9.

A force causes an acceleration of 10 m s-2 in a body of mass 500 g. What acceleration will be caused by the same force in a body of mass 5 kg?

Ans:

Step 1: Determining the Force Applied

We start with the first object. It has a mass of 500 grams. To use standard physics formulas, we convert this into kilograms:

500 grams = 0.5 kilograms

This object accelerates at 10 m/s². According to Newton’s second law of motion, the force causing this acceleration is calculated by multiplying mass and acceleration:

Force (F) = mass × acceleration

F = 0.5 kg × 10 m/s²

F = 5 Newtons

So, the force being applied is 5 N.

Step 2: Calculating the New Acceleration

Now, we take the exact same 5 N force and apply it to the second object, which has a mass of 5 kg.

Using the same law, but now rearranged to solve for acceleration:

Acceleration (a) = Force / mass

Plugging in our values:

a = 5 N / 5 kg

a = 1 m/s²

Final Result

Therefore, when the same 5 Newton force acts on the 5 kg mass, it will produce an acceleration of 1 meter per second squared.

Question 10.

A force acts for 0.1 s on a body of mass 2.0 kg initially at rest. The force is then withdrawn and the body moves with a velocity of 2 m s-1. Find the magnitude of the force.

Ans:

Question 11.

A body of mass 500 g, initially at rest, is acted upon by a force which causes it to move a distance of 4 m in 2 s. Calculate the force applied.

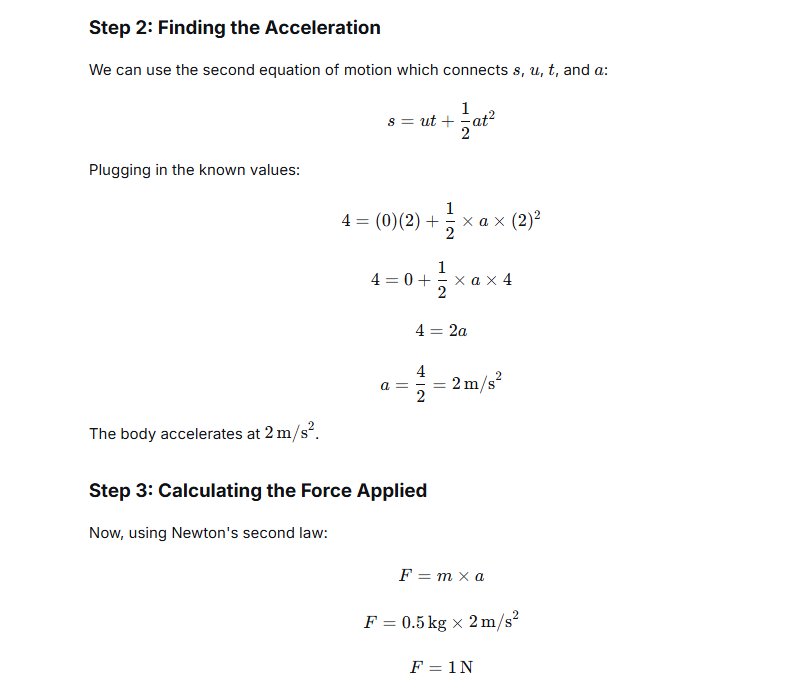

Ans:

Step 1: Understanding the Problem

We are given:

- Mass of the body, m=500g=0.5kg

- Initial velocity, u=0m/s (since it starts from rest)

- Distance travelled, s=4m

- Time taken, t=2s We need to find the applied force, F.

- From Newton’s second law, F=ma.

We know the mass m, but we need to find the acceleration a.

Question 12.

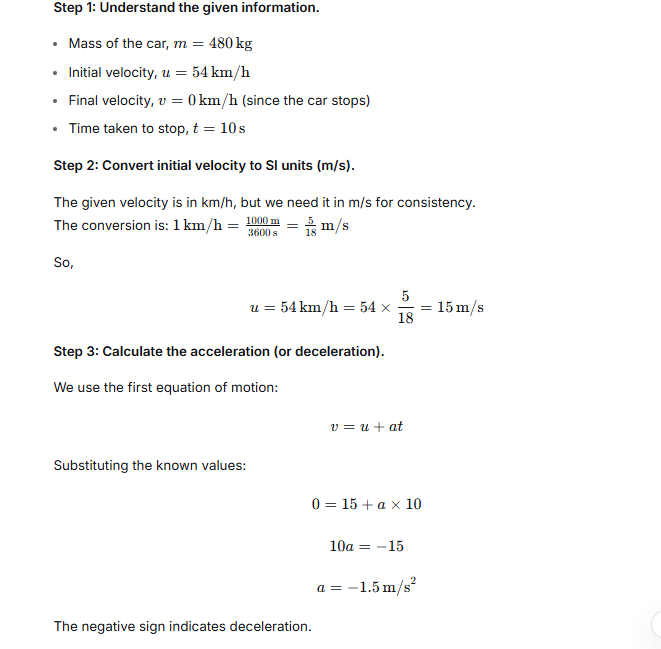

A car of mass 480 kg moving at a speed of 54 km h-1 is stopped by applying brakes in 10 s . Calculate the force applied by the brakes .

Ans:

Question 13.

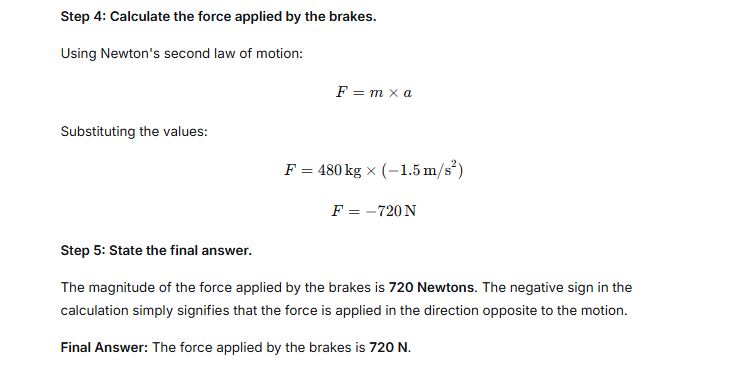

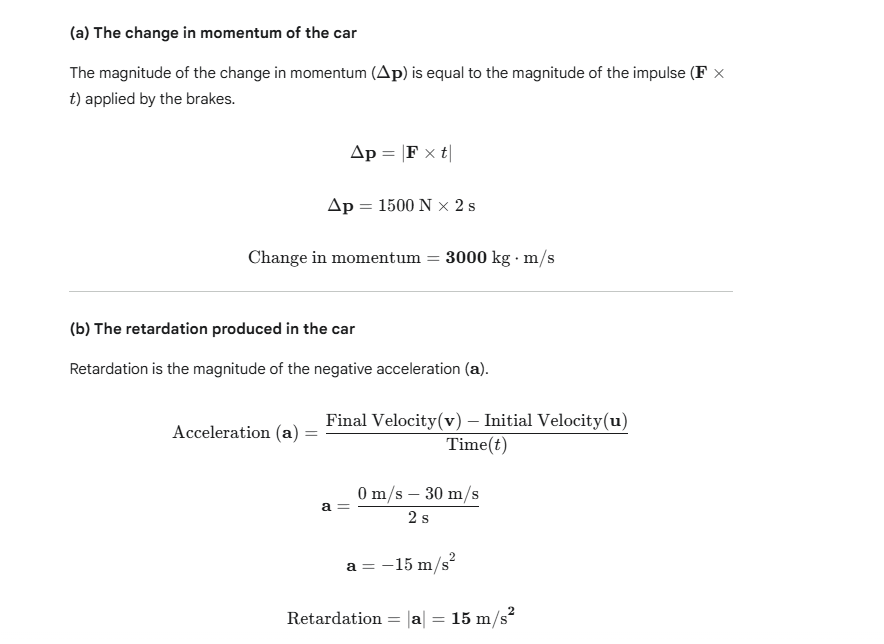

(a) A car is moving with a uniform velocity 30 ms-1. It is stopped in 2 s by applying a force of 1500 N through its brakes. Calculate the following values : The change in momentum of the car.

(b) A car is moving with a uniform velocity 30 ms-1. It is stopped in 2 s by applying a force of 1500 N through its brakes. Calculate the following values : The retardation produced in the car.

(c) A car is moving with a uniform velocity of 30 ms-1. It is stopped in 2 s by applying a force of 1500 N through its brakes. Calculate: The mass of the car.

Ans:

Question 14.

A bullet of mass 50 g moving with an initial velocity 100 m s-1 strikes a wooden block and comes to rest after penetrating a distance 2 cm in it. Calculate: (i) Initial momentum of the bullet, (ii) Final momentum of the bullet, (iii) Retardation caused by the wooden block and (iv) Resistive force exerted by the wooden block.

Ans:

Exercise 3 (D)

Question 1.

State the usefulness of Newton’s third law of motion .

Ans:

The usefulness of Newton’s Third Law of Motion lies in its fundamental explanation of how motion is generated and sustained through interaction between objects. It explains that forces never exist alone; they always occur in equal and opposite pairs.

The law’s primary usefulness is in:

- Explaining Propulsion and Movement: It is the underlying principle for all forms of locomotion.

- Walking/Running: You exert a backward action force on the ground due to friction; the ground exerts an equal and opposite forward reaction force that propels you forward.

- Rocket Propulsion: A rocket expels hot gas backward (action); the exhaust gas exerts an equal and opposite force, or thrust, on the rocket, pushing it forward (reaction).

- Engineering and Design: It is critical for calculating the forces on structures, vehicles, and machinery.

- Engineers use it to design bridges and buildings, ensuring the structure can withstand the equal and opposite reaction forces exerted by the ground, wind, or internal loads.

- It is fundamental in aerospace engineering for calculating lift and thrust in aircraft and spacecraft.

- Understanding Stability (Static Equilibrium): The law helps analyze why stationary objects remain at rest. For a book resting on a table, the book exerts a downward force (action) on the table, and the table exerts an equal and opposite upward force (normal force, reaction) on the book, resulting in a net force of zero on the book.

- Deriving the Law of Conservation of Momentum: The Third Law is essential for proving that in a closed system, the total momentum remains constant, which is a powerful tool for analyzing collisions and explosions.

Question 2.

State Newton’s third law of motion.

Ans:

Newton’s third law of motion, often called the Law of Action and Reaction, is formally stated as:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

This means that whenever one object exerts a force on a second object (the action), the second object simultaneously exerts a force of equal magnitude and in the opposite direction on the first object (the reaction).

- These forces always occur in pairs.

- The forces act on two different objects, which is why they do not cancel each other out.

For example, when a rocket pushes hot gas downward (action), the gas pushes the rocket upward with the same amount of force (reaction/thrust).

Question 3.

State and explain the law of action and reaction. by giving two examples.

Ans:

The Law of Action and Reaction is Newton’s Third Law of Motion.

Statement of the Law

Newton’s Third Law of Motion states:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

This means that forces always occur in pairs. If object A exerts a force on object B (the action), then object B simultaneously exerts a force of equal magnitude and opposite direction on object A (the reaction). These action and reaction forces never act on the same object.

Examples

1. Rocket Propulsion

- Action: The rocket engine rapidly burns fuel, creating hot gases that are forcefully expelled downward out of the exhaust nozzle.

- Reaction: The expelled gases exert an equal and opposite force upward on the rocket body. This reaction force is called thrust, and it is what propels the rocket into space. The rocket doesn’t need to push against the air or the ground; it pushes against the mass of its own exhaust gas.

2. A Person Walking

- Action: When a person walks, their foot pushes the ground backward and slightly downward (due to friction).

- Reaction: The ground simultaneously pushes the foot (and thus the person) with an equal and opposite force that is forward and slightly upward. This forward component of the reaction force is what accelerates the person and allows them to move.

Question 4.

(a) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : Firing a bullet from a gun

(b) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : Hammering a nail

(c) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : A book lying on a table

(d) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : A moving rocket

(e) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : A person moving on the floor

(f) Name and state the action and reaction in the following case : A moving train colliding with a stationary train

Ans:

The Law of Action and Reaction

The Law of Action and Reaction is Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which states:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

In an interaction between two objects, the forces they exert on each other are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction, and they act on different objects.

(a) Firing a bullet from a gun

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Force exerted by the gun on the bullet | Bullet |

| Reaction | Force exerted by the bullet on the gun | Gun |

| Result | The gun recoils (moves backward). |

(b) Hammering a nail

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Force exerted by the hammer on the nail | Nail |

| Reaction | Force exerted by the nail on the hammer | Hammer |

| Result | The nail is driven into the wood, and the hammer’s motion is stopped or reversed. |

(c) A book lying on a table

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Weight of the book (Gravitational force exerted by the Earth on the book) | Book |

| Reaction | Normal Force exerted by the table on the book (or the force exerted by the book on the Earth) | Book (or Earth) |

| Result | The book remains at rest because the Normal Force balances the weight. |

(d) A moving rocket

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Force exerted by the rocket on the exhaust gases (pushing the gases backward) | Exhaust Gases |

| Reaction | Force exerted by the exhaust gases on the rocket | Rocket |

| Result | This reaction force is called thrust, which propels the rocket forward. |

(e) A person moving on the floor

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Force exerted by the foot on the floor (pushing backward) | Floor |

| Reaction | Force exerted by the floor on the foot (pushing forward due to friction) | Person |

| Result | The forward reaction force accelerates the person. |

(f) A moving train colliding with a stationary train

| Interaction | Name of Force | Object it Acts On |

| Action | Force exerted by the moving train on the stationary train | Stationary Train |

| Reaction | Force exerted by the stationary train on the moving train | Moving Train |

| Result | Both trains exert forces of equal magnitude on each other, causing the momentum of the system to be conserved. The moving train slows down, and the stationary train moves forward. |

Question 5.

Explain the motion of a rocket with the help of Newton’s third law.

Ans:

The motion of a rocket is an excellent demonstration of Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

How Rocket Propulsion Works

The rocket system involves an interaction between the rocket body and the exhaust gases it expels.

- Action Force (The Push):

- Inside the rocket’s combustion chamber, fuel and oxidizer are burned, generating a massive volume of hot, high-pressure gases.

- The rocket engine forces these gases out of the exhaust nozzle at extremely high velocity in the downward (or backward) direction.

- The action is the large, forceful push exerted by the rocket on the exhaust gases.

- Reaction Force (Thrust):

- In accordance with Newton’s Third Law, the exhaust gases exert an equal and opposite force back on the rocket body.

- This resulting reaction force is called Thrust, and it acts in the upward (or forward) direction, propelling the rocket off the launch pad and into space.

Question 6.

When a shot is fired from a gun, the gun is recoiled. Explain.

Ans:

The backward jerk experienced when firing a gun, commonly known as “kickback,” is a direct result of a fundamental physical rule concerning motion.

To understand this, imagine the gun and the bullet inside it as a single, isolated pair. Before the trigger is pulled, this pair is completely still. Its overall tendency to move—its combined momentum—is precisely zero.

The process is set in motion by the ignition of the gunpowder. This creates a rapidly expanding gas that acts like a powerful spring, pushing in all directions within the confined barrel. It applies intense pressure, launching the bullet forward. However, the gas presses with identical strength against the back of the gun’s chamber.

This creates a pair of opposing pushes. While the bullet is driven forward down the barrel, the gun itself is driven backward with equal force. This isn’t merely a reaction in the everyday sense; it is a strict, one-to-one physical exchange.

Because momentum must be preserved and the system started with a total of zero, it must end with zero. The lightweight bullet races away with a certain amount of forward momentum. To perfectly counterbalance this, the much heavier gun must acquire an equal amount of momentum in the reverse direction. Since the gun’s mass is vastly greater, it achieves this balance by moving backward at a significantly slower speed. This backward motion is the recoil we feel—a powerful, sudden shove against the shooter’s hand and shoulder.

In essence, the gun is not just “reacting” to the bullet’s launch; it is an active participant in a forced exchange of motion, compelled by nature’s law to balance the scales.

Question 7.

When you step ashore from a stationary boat, it tends to leave the shore. Explain.

Ans:

This phenomenon is a perfect illustration of Newton’s Third Law of Motion (The Law of Action and Reaction) and the Conservation of Momentum.

Explanation using Newton’s Third Law

- Action: As you step forward toward the shore, your feet exert a forceful push backward on the boat. This is the action force.

- Reaction: According to Newton’s Third Law, the boat exerts an equal and opposite force forward on your body, propelling you onto the shore. This force is the reaction force.

- Result: Since the boat is resting on the water (a low-friction surface), the backward force from your push causes it to move away from the shore (recede) as you move forward.

Explanation using Conservation of Momentum

The principle of conservation of momentum also applies here:

- Before: Before you step, the total momentum of the boat-person system is zero, as both are stationary.

Question 8.

When two spring balances joined at their free ends are pulled apart, both show the same reading. Explain.

Ans:

When two spring balances joined at their free ends are pulled apart, both show the same reading because of Newton’s Third Law of Motion, the Law of Action and Reaction.

Explanation

- The Interaction: The two spring balances, let’s call them Balance A and Balance B, interact directly with each other at the point where they are joined.

- Action Force: When you pull on Balance A, it transmits a force to Balance B. This force is the action force exerted by Balance A on Balance B.

- Reaction Force: According to Newton’s Third Law, Balance B simultaneously exerts an equal and opposite force back on Balance A. This is the reaction force exerted by Balance B on Balance A.

- Reading the Balances:

- Balance B reads the magnitude of the force acting on its hook (the action force from A).

- Balance A reads the magnitude of the force acting on its hook (the reaction force from B).

Since the law dictates that the magnitude of the action force and the reaction force must be equal , both spring balances will always display the same numerical reading, regardless of how hard they are pulled, as long as they are connected and the system is in equilibrium or accelerating together.

This demonstrates that forces always exist as mutual, equal, and opposite pairs.

Question 9.

To move a boat ahead in water, the boatman has to push the water backwards by his oar. Explain this statement.

Ans:

The movement of a rowboat is a clever trick played with forces, where the real push comes from an unexpected source. The rower’s effort doesn’t pull the boat forward; it instead creates a situation where the water itself does the pushing.

It begins with the oar. When the blade is driven backward through the water by the rower’s pull, it acts like a solid wall shoving against the water. This action forces a mass of water to move backward.

The water resists this displacement. It pushes back against the face of the oar blade with a strength that matches the force the rower applied. This resistance from the water is not random; it is a direct and equal reply, aimed in the exact opposite direction—forward.

The oarlock is the crucial pivot in this exchange. It acts as a fulcrum, allowing the rower’s backward pull on the handle to be converted into a backward push by the blade. Because this pivot is attached to the boat, the forward-pushing answer from the water is transferred through the oar and into the hull.

So, the boat is not being dragged forward by the oar. It is being shoved from the front by the reactive push of the water, a force generated only because the rower first used the oar to push water the other way. The rower, in essence, uses the water as a solid anchor against which to lever the boat ahead.

Question 10.

A person pushing a wall hard is liable to fall back. Give a reason.

Ans:

A person pushing a wall hard is liable to fall back because of Newton’s Third Law of Motion, the Law of Action and Reaction.

Here is the explanation:

- Action Force: When the person pushes the wall, they exert a large force on the wall in the forward direction. This is the action force.