This chapter reveals that fluids—both liquids and gases—exert pressure in all directions, a force that is both invisible and powerful. The pressure within a liquid is not uniform; it increases significantly with depth. This is because the weight of the liquid above pushes down on the layers below. A liquid at a greater depth must support more weight, resulting in higher pressure. This principle explains why dams are built with thicker walls at the bottom and why a person feels more pressure in their ears when diving deep underwater. Furthermore, this liquid pressure depends only on the height of the liquid column and its density, not on the shape or surface area of the container. This is why water seeks its own level, and it forms the basis for the interconnected vessels principle.

The transmission of this pressure leads to a crucial application: Pascal’s Law. This law states that a change in pressure applied to an enclosed fluid is transmitted undiminished to every portion of the fluid and the walls of the container. We harness this principle in hydraulic machines like lifts and brakes. By applying a small force to a small-area piston, we create a pressure that is transmitted to a larger-area piston, which then generates a massive output force. This allows us to multiply force dramatically, making it possible to lift heavy cars in a garage with minimal effort.

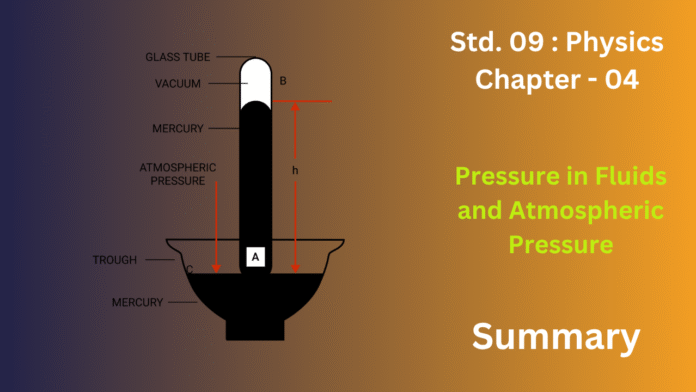

Shifting from liquids to gases, the chapter explores atmospheric pressure. Our atmosphere is a vast ocean of air, and its weight creates a pressing force on everything at the Earth’s surface. This is demonstrated by classic experiments, such as the mercury barometer invented by Torricelli, which measures this pressure. We don’t feel this colossal force because the pressure inside our bodies balances it. This atmospheric pressure is utilized in everyday tools like drinking straws and syringes; when we suck out the air, the outside atmospheric pressure pushes the liquid up to fill the vacuum. The chapter also explains that this air pressure decreases as we ascend to higher altitudes, as there is less air above us pushing down, which is why aircraft cabins must be pressurized.

Exercise 4 (A)

Question 1.

Define the term thrust. State its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Thrust is a mechanical force that describes a powerful, directed push. It is the reaction force exerted by an object when it expels mass at high speed, propelling itself in the opposite direction.

In simpler terms, thrust is the driving push that moves a vehicle like a rocket or a jet plane forward. It is generated according to Newton’s third law; as the engine forces exhaust gases backward, the gases push the engine (and the vehicle attached to it) forward with an equal force. This forward force is thrust.

The S.I. unit of thrust is the newton (N). Since thrust is a type of force, it is measured in newtons, which is defined as the force needed to accelerate a one-kilogram mass at a rate of one meter per second squared (1 N = 1 kg·m/s²).

Question 2.

What is meant by pressure? State its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Pressure describes how concentrated a force is over a specific area. It’s the measure of how much push or squeeze is being applied onto a surface.

Think of it this way: the same total force can feel very different depending on how much space it’s spread over. For instance, the force of your body weight is the same whether you stand on the ground in flat shoes or in high heels. But in high heels, that same force is concentrated into a much smaller area, resulting in a much higher pressure—which is why the heels sink into soft ground more easily.

In scientific terms, pressure is calculated as the amount of force acting perpendicularly on a surface, divided by the area of that surface.

Its S.I. unit is the pascal (Pa). One pascal is defined as a force of one newton pushing on an area of one square metre.

1 pascal (Pa)=1 newton per square metre (N/m²)

Question 3.

(a) What physical quantity is measured in bar?

(b) How is the unit bar related to the S.I. unit pascal?

Ans:

(a) Physical Quantity Measured in Bar

The unit bar is used to measure pressure.

Pressure, in simple terms, is the amount of force applied over a specific area. You encounter it in everyday life, such as when checking the air pressure in a car tire or hearing a weather report about atmospheric pressure.

(b) Relationship Between Bar and Pascal

The relationship between the bar and the pascal is direct and fixed:

1 bar is exactly equal to 100,000 pascals.

We can express this as:

1 bar = 10⁵ Pa

This shows that the bar is a much larger unit than the pascal. One pascal is a very small amount of pressure, so using the bar (or the kilopascal, kPa) is often more practical for measuring common pressures like tire inflation or atmospheric conditions. For example, standard atmospheric pressure is about 1.013 bar, which is a much more convenient number than 101,300 pascals.

Question 4.

Define one pascal (Pa), the S.I. unit of pressure.

Ans:

Think of pressure as a measure of how concentrated a force is over a certain area.

With that in mind, we define the pascal (Pa) by building it from its fundamental units. It is the pressure that results when a force of one newton is spread evenly over a surface area of exactly one square meter.

Since a newton is a relatively small unit of force (roughly the weight of a small apple), and a square meter is a sizable area, one pascal represents a very gentle, barely noticeable pressure. It is the gentle, distributed push you would feel if that single apple were laid flat across the surface of a large coffee table.

In its simplest terms: One pascal is one newton per square meter.

Question 5.

State whether thrust is a scalar or vector?

Ans:

Thrust is a vector quantity.

The reason for this is that thrust is not just about an amount; it is a force that acts in a specific direction.

To understand why:

- A scalar quantity is defined only by its magnitude (size or amount). Examples include mass, time, and temperature. Saying “the engine produces 50,000 Newtons of thrust” gives the magnitude.

- A vector quantity must be fully described by both magnitude and a direction. To completely describe thrust, you must state both its amount and the direction it is applied. For example, “the rocket engines produce 50,000 Newtons of thrust directed downward to lift the spacecraft upward.”

Question 6.

State whether pressure is a scalar or vector?

Ans:

Pressure is classified as a scalar quantity.

The reason for this lies in its definition. Pressure is defined as the magnitude of the force component acting perpendicularly (normal) on a surface, divided by the area of that surface.

While force is a vector (having both magnitude and direction), pressure itself does not have a specific directional property associated with its nature. It simply transmits its magnitude equally in all directions at a point within a fluid at rest.

Think of it this way: when you inflate a balloon, the air pressure inside pushes outward against the inner walls equally in every direction. It does not push only left or only down. This isotropic (same in all directions) behavior is a definitive characteristic of a scalar quantity. It possesses magnitude but no single, defined direction.

Question 7.

Differentiate between thrust and pressure.

Ans:

| Feature | Thrust | Pressure |

| Definition | The force acting perpendicularly (normal) to a surface. | The thrust or force acting per unit area of a surface. |

| Formula | Thrust = Force (F) | Pressure = Area / Thrust or P=A /F |

| Nature | Vector quantity (has both magnitude and direction). | Scalar quantity (has only magnitude). |

| SI Unit | Newton (N), as it is a force. | Pascal (Pa) or N/m2. |

| Effect | The total force exerted on the surface. | The effect or intensity of the force on a unit area. A small area results in high pressure for the same thrust. |

| Examples | The upward force exerted by a fluid on a submerged object (Upthrust/Buoyant force); the force that propels a rocket or jet engine. | The force on the blade of a sharp knife (small area = high pressure); atmospheric pressure; the pressure inside an inflated balloon. |

Question 8.

How does the pressure exerted by thrust depend on the area of surface on which it acts? Explain with a suitable example.

Ans:

The pressure exerted by a thrust depends inversely on the area of the surface on which it acts. This means that for a constant thrust, a smaller contact area results in significantly higher pressure, while a larger contact area results in much lower pressure.

This relationship is best understood through the formula:

Pressure = Thrust / Area

You can see that pressure and area are on opposite sides of the fraction. If the Area in the denominator gets smaller, the overall value of Pressure gets larger, provided the Thrust (the force applied perpendicularly) remains the same.

A Concrete Example: The Knife’s Edge

Consider the simple action of cutting a vegetable.

A sharp knife has a blade that tapers to a very fine edge. This means the cutting edge has an extremely small surface area. When you apply a downward thrust (force) with the knife, all of that force is concentrated onto that tiny edge. The resulting pressure becomes immense—so high that it easily overcomes the strength of the vegetable’s fibers, allowing the blade to slice through cleanly.

Now, imagine trying to cut the same vegetable with a dull knife. A dull knife has a wider, rounded edge, meaning it has a much larger surface area in contact with the vegetable. If you apply the same amount of thrust as you did with the sharp knife, this force is now spread out over this larger area. The resulting pressure is therefore much lower. It is insufficient to sever the fibers effectively, and the knife will tend to crush or bruise the vegetable rather than cutting it smoothly.

Thus, the same thrust produces a world of difference in outcome solely because of the surface area it acts upon. This inverse relationship is why all cutting and piercing tools—from needles and nails to axes and spears—are designed with a sharp point or edge.

Question 9.

Why is the tip of an allpin made sharp?

Ans:

The sharp tip of a pin is a brilliant exploitation of a simple principle of physics: concentrating force to overcome resistance.

Think of the difference between trying to push a blunt thumbtack into a corkboard and a sharp one. The blunt one will press against a wide area of the cork’s surface, and the cork fibers, sharing the push among themselves, resist easily. The sharp pin, however, is a trick of geometry. It gathers the entire pushing force from your hand and focuses it onto a single, minuscule point at its tip.

This incredible concentration of energy is like the difference between pressing a block of wood against your skin and pressing a needle. The block spreads the force harmlessly, while the needle’s point applies the same total force to such a tiny area that it effortlessly pierces the surface.

For a pin, this means it can part the woven threads of fabric or push aside the particles of a wall with minimal effort from the user. The sharpness ensures that all the energy from your push is used not to just press broadly, but to cut and separate at a microscopic level, allowing the pin to slide in smoothly and hold its place.

Question 10.

(a) Explain the following statement: It is easier to cut with a sharp knife than with a blunt one.

(b) Explain the following statement:Sleepers are laid below the rails.

Ans:

(a)

This difference comes down to how force is concentrated. When you push down on a knife, you apply a certain amount of force.

A sharp knife has a very fine edge, meaning the blade tapers down to an extremely thin line. This tiny edge is the only part that makes contact with the object you’re cutting. As a result, all the downward force from your hand is focused onto a miniscule area. This intense concentration of force creates immense pressure at the point of contact, allowing the blade to pierce and separate the material with ease.

A blunt knife, in contrast, has a wider, rounded edge. The same amount of force from your hand is now spread out over a much larger surface area. This drastically reduces the pressure exerted on the material. Instead of slicing through cleanly, the blade tends to crush and tear its way through, requiring significantly more effort.

Think of it like the difference between pressing a pin and a bottle cap into your skin with the same force. The pin’s point concentrates the force to create high pressure and pierces easily, while the bottle cap spreads the force out, creating low pressure and causing no puncture.

(b) Sleepers are laid below the rails.

Sleepers (or railroad ties) are the horizontal slabs of wood or concrete placed underneath and across the steel rails. Their primary job is to distribute weight and prevent sinking.

A train is an immensely heavy object. Without sleepers, the narrow steel rails would bear the entire weight of the passing train, concentrating it on two very thin lines. On soft ground like soil or gravel, this enormous pressure would cause the rails to sink, bend, and become misaligned, making the track unstable and dangerous.

The sleepers solve this by acting as a stable, wide foundation. They lie perpendicular to the rails, effectively “catching” the load from the rails and spreading it out over a much wider area of the ground beneath. This distribution dramatically reduces the pressure on the ground, preventing the rails from sinking and ensuring the track remains level, secure, and able to handle the train’s weight safely.

In essence, sleepers function like snowshoes for a train track. Just as snowshoes stop a person from sinking into soft snow by spreading their weight, sleepers stop the rails from sinking into the ground by spreading the train’s weight.

Question 11.

What is a fluid?

Ans:

A fluid is a substance that cannot resist a changing shape when it is met with a force. Its primary nature is to yield and to flow. This category of matter includes both liquids and gases.

What truly defines a fluid is the relationship between its molecules and how they respond to pressure. Unlike in a solid, where molecules are locked in a fixed structure, the molecules in a fluid are mobile. They can slide past one another with relative freedom.

When you apply a push or a shear force to a fluid, it does not develop a permanent resistance. Instead, it contorts and moves, continuously deforming for as long as the force is applied. A liquid, like water, will flow to fill the bottom of a container, adopting its shape while retaining a nearly fixed volume. A gas, like air, will expand to fill every available space, its volume changing readily.

In essence, a fluid is any substance that offers no lasting opposition to a change in its form. It is defined by its readiness to travel, to adapt, and to be reshaped by the slightest imbalance in force, making all liquids and gases kin in their behavior.

Question 12.

What do you mean by the term fluid pressure?

Ans:

Think of fluid pressure as a hidden, constant push that a fluid—which can be either a liquid or a gas—exerts on every single surface it touches. It is a silent force that acts in all directions at once.

This pressure originates from the countless, tiny particles that make up the fluid. These particles are never still; they are in a state of continuous, frantic motion. In a liquid, they slide and jostle past one another. In a gas, they fly around at high speeds.

As these particles move, they constantly collide with each other and with any object placed within the fluid. Each collision delivers a tiny, individual push. Fluid pressure is the combined effect of a vast number of these microscopic collisions happening every second. It is the total force of all these tiny pushes spread over a specific area.

A key feature of this pressure is that it pushes equally in all directions at a given point. If you submerge your hand in water, you feel this push against your palm, the back of your hand, and your fingers simultaneously. It’s not a one-directional force like wind; it is a truly surrounding squeeze.

The strength of this push isn’t constant everywhere. It increases with depth. The deeper you go into a fluid, the greater the weight of the fluid above you, and the more intensely the particles are squeezed together, leading to more forceful collisions. This is why a scuba diver feels the increasing squeeze on their eardrums as they descend, or why a dam must be much thicker at its base than at the top to withstand the greater push from the deep water.

Question 13.

How does the pressure exerted by a solid and fluid differ?

Ans:

The way a solid and a fluid exert pressure stems from a fundamental difference in their physical structure, leading to two distinct behaviors.

A solid exerts pressure in a defined, directional manner. Because a solid has a rigid structure, any force applied to it is transmitted in a specific direction. For instance, the pointed heel of a shoe applies pressure straight down onto a floor. The force is confined to the area of contact and points in the direction it was pushed. The pressure exists only where the solid makes contact and is directed along the line of the applied force.

A fluid (which includes both liquids and gases), in contrast, exerts pressure in all directions at any given point. This is because the molecules in a fluid are not locked in place but move freely. When a force is applied, it is transmitted equally in all directions by these mobile particles. When you are submerged in water, you feel the water’s push against your front, back, sides, and everywhere on your body simultaneously. This pressure isn’t just downward; it’s omnidirectional. Furthermore, fluid pressure increases with depth, as the weight of the fluid above creates a greater force, which is then transmitted in all directions.

In essence, the key difference is this: A solid presses down along a specific path, while a fluid presses inward from all sides at once. A solid’s pressure is directional and localized, but a fluid’s pressure is encompassing and pervasive.

Question 14.

Describe a simple experiment to demonstrate that a liquid enclosed in a vessel exerts pressure in all directions.

Ans:

The Balloon and Water Fountain Experiment

This experiment visually shows water being forced out from all sides of a flexible container, proving the liquid’s internal pressure is omnidirectional.

You will need:

- A large, sturdy, transparent plastic bag (like a freezer bag).

- Water.

- A few rubber bands.

- A sharp pushpin or thumbtack.

- A tray or a basin to catch water.

A helper (optional but useful).

Procedure:

- Prepare the “Vessel”: Take the plastic bag and fill it about three-quarters full with water. Seal the top of the bag tightly, squeezing out the excess air, and secure it with a rubber band to prevent any leaks.

- Create the “Walls”: Your sealed, water-filled bag now represents the enclosed vessel.

- Demonstrate the Pressure:

- Hold the bag upright over the tray. With your other hand, quickly and carefully poke a hole in the front of the bag with the pushpin. Observe a stream of water jetting out forwards.

- Now, while the first hole is still leaking, poke a second hole in the top of the bag. You will immediately see a new stream of water shooting upwards.

- Next, poke a hole in one side of the bag. A stream will jet out sideways.

- Finally, poke a hole in the bottom. A strong stream will flow downwards.

Observation:

You will see distinct jets of water spurting out from every single hole you create, regardless of its position—top, bottom, front, back, or sides. The water is not just falling out due to gravity; it is being actively pushed out by the pressure within the bag. The upward jet from the top hole is the most conclusive, as it proves the pressure is not just downward (from gravity) but acts forcefully in all directions, even against gravity.

Conclusion:

The water inside the sealed bag exerts a force perpendicular to the inner surface of the bag at every point. Because the bag is flexible, this force results in water being ejected from any opening made in the container. The fact that jets appear from holes in the top, sides, and bottom simultaneously proves that the enclosed liquid exerts pressure in all directions equally.

Question 15.

State three factors on which the pressure at a point in a liquid depends.

Ans:

The pressure experienced at any specific location within a liquid, like water in a tank or the ocean, is determined by three key elements:

- The Vertical Height of Liquid Above: The most direct influence is the depth of the point itself. The deeper you go, the greater the weight of the liquid column pressing down from above. A point at the bottom of a deep swimming pool feels far more pressure than a point just below the surface, because it supports a much taller column of water.

- The Density of the Liquid: The substance of the liquid itself is crucial. A denser liquid, like seawater, has more mass packed into the same volume compared to a lighter liquid like freshwater. This means that at an identical depth, the heavier liquid will exert a stronger push because the column of liquid above the point simply weighs more.

- The Local Strength of Gravity: The force that gives the liquid its weight is gravity. The pressure we calculate is directly dependent on the value of gravitational acceleration (g). If you could take a container of water to the Moon, where gravity is weaker, the pressure at the bottom would be significantly less because the liquid column would be lighter. On a larger planet with stronger gravity, the same depth would produce a much higher pressure.

Question 16.

Write an expression for the pressure at a point inside a liquid. Explain the meaning of the symbols used.

Ans:

The pressure at a specific point submerged in a liquid is given by the expression:

P = P₀ + ρgh

Here is the meaning of each symbol in this relationship:

- P: This represents the total pressure at the point inside the liquid. It is the combined force per unit area experienced at that exact location, measured in pascals (Pa).

- P₀: This is the external pressure applied at the liquid’s surface. Most commonly, this is the atmospheric pressure pushing down on the liquid from above. However, it could be any pressure, such as that from a piston in a closed container.

- ρ (the Greek letter ‘rho’): This symbolizes the density of the liquid. It tells us how much mass of the liquid is packed into a given volume. A denser liquid, like mercury, will create a greater increase in pressure with depth than a less dense one, like water.

- g: This is the acceleration due to gravity. Its constant pull downward is what gives the weight to the column of liquid above the point, and is thus fundamental to the pressure we calculate.

- h: This denotes the vertical depth of the point from the liquid’s surface. It is not the length of the container, but the straight-down distance from the surface to the point in question. The pressure increases linearly as you go deeper.

In essence, the formula P = P₀ + ρgh tells us that the total pressure at a point is the sum of the pressure already on the liquid’s surface plus the pressure exerted by the weight of the liquid column directly above that point.

Question 17.

Deduce an expression for the pressure at depth inside a liquid.

Ans:

Imagine a point submerged deep within a stationary liquid. To find the pressure at this point, we don’t just consider the liquid directly above it; we must account for the entire column of fluid pressing down from the surface.

Let’s visualize a cylindrical column of the liquid with a flat top and bottom, both of area A. The top of this cylinder is right at the free surface of the liquid, open to the atmosphere. The bottom is at the depth *h* where we want to find the pressure.

This column of liquid is at rest. Therefore, all the forces acting upon it must be in equilibrium.

Three primary vertical forces act on our imaginary cylinder:

- Atmospheric Force, F₁: At the top surface, the atmosphere is pressing down. This force is the atmospheric pressure (P₀) multiplied by the area:

- F₁ = P₀ A

- Weight of the Liquid, W: The cylinder itself has weight. Its volume is the area of the base multiplied by the height (A × h). If the liquid has a density ρ, then its mass is ρ × (A h). Therefore, its weight is:

- W = ρ (A h) g

- Upward Force from the Liquid Below, F₂: The liquid beneath the cylinder must push upward to support the weight of the cylinder and the force from the atmosphere above it. This upward push is the pressure (P) at depth *h* multiplied by the area of the base. This is the force we are ultimately solving for:

- F₂ = P A

Since the fluid is in equilibrium, the upward force must perfectly balance the sum of the two downward forces.

Balancing the Forces:

F₂ = F₁ + W

Substituting the expressions we have:

P A = (P₀ A) + (ρ A h g)

Notice that the cross-sectional area A is a common factor in every term. We can divide the entire equation by A to eliminate it, which is a powerful simplification showing that the pressure is independent of the shape or area we imagine.

This leaves us with the fundamental expression for pressure at depth in a liquid:

P = P₀ + ρ g h

Where:

- P is the total pressure at the depth *h*.

- P₀ is the pressure at the liquid’s surface (usually atmospheric pressure).

- ρ is the density of the liquid.

- g is the acceleration due to gravity.

- h is the vertical depth from the surface.

This result shows that the pressure increases linearly with depth, driven directly by the weight of the fluid column above it, and is always greater than the surface pressure P₀.

Question 18.

How does the pressure at a certain depth in sea water differ from that at the same depth in river water? Explain your answer.

Ans:

The pressure at a specific depth is fundamentally the weight of the water column above that point pressing down. While the depth is identical in both the sea and the river, the key difference lies in the nature of that water column.

Seawater is not pure water; it has a significant amount of salts and minerals dissolved in it. This makes it denser and heavier for a given volume. Imagine two identical columns, one filled with seawater and the other with fresh river water. The column of seawater would simply weigh more.

This difference in weight is what creates the difference in pressure. At the same depth, you are supporting a taller, heavier stack of water in the ocean than you are in the river. The seawater is essentially a heavier fluid, and so it presses down with greater force at every level.

You can think of it like the difference between standing under a tall column of light foam versus a tall column of heavy mud. Even if the columns are the same height, the mud, being denser, would push down on you with much greater force. Similarly, the denser seawater exerts a stronger push, or higher pressure, than river water at the same depth.

Question 19.

Pressure at the free surface of a water lake is P1, while at a point at depth h below its free surface is P2. (a) How are P1 and P2 related? (b)Which is more P1 or P2?

Ans:

(a) The relationship between the pressure at the free surface (P1) and the pressure at a depth h (P2) is direct and additive. The pressure P2 is equal to the surface pressure P1 plus the pressure exerted by the weight of the water column above that point. This is mathematically expressed as:

P₂ = P₁ + ρgh

where:

- ρ is the density of water,

- g is the acceleration due to gravity, and

(b) Based on the relationship above, P₂ is greater than P₁. This is because P₂ includes the surface pressure P1 and the additional pressure from the water above it (ρgh), which is always a positive quantity. The deeper you go, the more water lies above, and thus the greater the pressure.

Question 20.

Explain why a gas bubble released at the bottom of a lake grows in size as it rises to the surface of the lake.

Ans:

Imagine you are at the bottom of a deep lake. The weight of all the water above you is pressing down, creating immense pressure. This pressure acts like an invisible, squeezing force on everything at that depth, including a tiny gas bubble just released from the lake bed.

This bubble is mostly empty space filled with air. The high pressure at the bottom forcefully compresses this air, packing the gas molecules tightly together and making the bubble start small.

As the bubble begins its journey upwards, it moves through layers of water that have less and less water above them. With each foot it rises, the weight of the water pressing down from above decreases. This means the squeezing pressure surrounding the bubble is steadily weakening.

The gas molecules inside the bubble have a natural tendency to move apart and fill the space available. They were previously held in a cramped state by the strong external pressure. As this external “squeeze” relaxes during the ascent, the trapped air can finally expand. The energized gas molecules push outward against the now-weaker water pressure, forcing the bubble’s flexible skin to stretch and its volume to increase.

In essence, the bubble grows because the confining force that kept it small is being steadily lifted on the way up. The rising bubble is like a compressed spring that is gradually released; the energy was always there, waiting for the pressure to drop so it could expand and claim more space.

Question 21.

A dam has broader walls at the bottom than at the top. Explain.

Ans:

A dam is built with thick, sprawling walls at its base and a narrower top because it must hold back an immense, heavy substance that pushes sideways with far greater force at the lowest depths.

Think of the body of water behind the dam not as a single, solid mass, but as a stack of individual layers. The weight of all the water from the surface down to the bottom accumulates, pressing down. This vertical weight translates into a horizontal push against the dam wall.

This sideways pressure is not the same at every depth. The water at the very surface presses with almost no force. But just a few meters down, the push becomes noticeable. At the very bottom of the reservoir, the water must support the weight of the entire column of water above it. This creates an intense outward pressure that is strongest at the deepest point.

A dam must be stable and resist toppling over from this powerful push. The massive, broad base serves two critical functions. First, the sheer volume of material provides the strength to withstand the immense pressure trying to rupture the wall at its lowest point. Second, the wide foundation anchors the entire structure, preventing the dam from being tipped forward by the water’s force. The shape is essentially a wedge, with the thick end facing the source of the pressure, ensuring it remains firmly planted.

In essence, the dam’s design mirrors the pressure profile of the water itself. It is a direct and logical response to a force that grows steadily stronger with depth, ensuring the structure remains immovable against the tremendous weight it contains.

Question 22.

Why do sea divers need special protective suit?

Ans:

Sea divers wear protective suits not as a mere uniform, but as a mobile life-support system that recreates the essential conditions of the surface world. The deep ocean is a fundamentally hostile environment for humans, and the suit is our crucial barrier against its three primary assaults: cold, pressure, and physical danger.

The first and most immediate threat is cold. Water draws heat away from the body nearly 25 times faster than air. Even in tropical waters, the temperature a few meters below the surface can be shockingly low, quickly sapping a diver’s body heat and leading to dangerous hypothermia. The protective suit, especially a wetsuit, fights this by trapping a thin layer of water between the diver’s skin and the neoprene rubber. The diver’s body warms this trapped water, and the insulating material of the suit drastically slows down the process of heat loss, turning the water itself into a warm, stable barrier.

The second, more insidious threat is pressure. For every 10 meters a diver descends, the pressure increases by one atmosphere. This immense squeeze doesn’t just compress the air in their lungs; it compresses the entire body. Without a suit, this pressure would be directly transmitted to the diver’s skin and tissues. A well-fitted suit, particularly a rigid drysuit, creates a protective layer that helps the body resist and manage this crushing force, acting as a flexible exoskeleton against the weight of the ocean.

Finally, the suit provides essential physical protection. The underwater world is not a smooth, empty swimming pool. It is full of potential hazards—razor-sharp coral, jagged rocks, stinging jellyfish, or abrasive surfaces on shipwrecks. A simple scrape that would be minor on land can become a serious, infection-prone wound in the saltwater environment. The tough material of the dive suit acts as a robust shield, preventing cuts, scrapes, and stings that could otherwise cut a dive short or lead to a medical emergency.

In essence, the diver’s suit is a portable pocket of human habitability, allowing us to briefly visit a world we were not built to inhabit. It keeps us warm, helps our bodies cope with crushing pressure, and shields our fragile skin from a landscape of hidden dangers.

Question 23.

State the laws of liquid pressure.

Ans:

The laws that govern how pressure behaves within a liquid are fundamental to understanding fluid mechanics. They can be summarized as follows:

- The Law of Depth: Pressure within a liquid increases with depth. The deeper you go, the greater the weight of the liquid above you, resulting in higher pressure.

- The Law of Equality at a Level: At any point within a body of liquid at rest, the pressure is the same in all directions. Furthermore, all points lying on the same horizontal level inside the liquid experience the same pressure.

- The Law of Direction: The pressure exerted by a liquid is always perpendicular (at a right angle) to the surface of the object or container it is in contact with. It does not push sideways against the walls.

- The Law of Container Shape: The pressure at a given depth depends only on the depth and the density of the liquid; it is completely independent of the shape, size, or volume of the container.

- The Law of Transmitted Force (Pascal’s Law): When pressure is applied to a confined liquid at any point, it is transmitted equally and undiminished in all directions throughout the liquid. This principle is what allows hydraulic systems to multiply force.

Question 24.

A tall vertical cylinder filled with water is kept on a horizontal table top. Two small holes A and B are made on the wall of the cylinder, A near the middle and B just Below the free surface of water. State and explain your observation.

Ans:

Observation: You would observe that the water jet streaming from hole B (just below the surface) is slow, weak, and travels only a short distance horizontally before curving down to the table. In contrast, the water jet from hole A (near the middle) is fast, forceful, and shoots out to a significantly longer horizontal distance.

Explanation:

The reason for this striking difference lies in how water pressure within the cylinder changes with depth.

Imagine the water in the cylinder as a column. The weight of all the water above a certain point pushes down on the water below it. This creates pressure.

- At hole B, very close to the surface, there is only a small amount of water above it pushing down. Therefore, the pressure at point B is low.

- At hole A, near the middle of the cylinder, a much taller column of water sits above it. The weight of this column creates a high pressure at point A.

When the holes are opened, this internal pressure is what propels the water outwards. The water is pushed out more forcefully from the high-pressure region than from the low-pressure one.

This difference in force translates directly to the speed of the exiting water. The high pressure at A forces the water out with a high initial speed, allowing it to travel a long, flat arc. The low pressure at B results in a slow, sluggish flow that cannot overcome the pull of gravity for long and falls almost straight down.

In essence, the water jet at the bottom “wins” the race in distance and force, not because of its position, but because it carries the energy of the greater weight of water pressing down from above.

Question 25.

(a)How does the liquid pressure on a diver change if: the diver moves to the greater depth

(b) How does the liquid pressure on a diver change if : The diver moves horizontally?

Ans:

(a) When the diver moves to a greater depth:

The liquid pressure on the diver increases significantly.

This happens because a diver submerged in water is supporting the weight of all the water directly above them. Imagine the water as a tall, heavy column standing on the diver’s shoulders. As the diver swims deeper, the height of this water column increases, making it taller and heavier.

Since pressure is caused by the weight of the fluid, carrying this heavier “column” of water results in a greater force being exerted on every part of the diver’s body. The deeper the diver goes, the more water there is above them, and the more intensely the water presses in from all directions.

(b) When the diver moves horizontally:

The liquid pressure on the diver remains the same, provided they are moving at a constant depth.

This is because the pressure in a liquid at rest depends only on the depth below the surface and the density of the liquid, not on horizontal position. Whether the diver is one meter away from their starting point or ten meters away, if they are swimming along at the same depth, the height of the water column above them remains unchanged.

The water is pushing down on them with the same force regardless of their horizontal location. Therefore, the squeezing pressure they feel from the water does not change as they move sideways.

Question 26.

State Pascal’s law of transmission of pressure.

Ans:

The Fundamental Rule of Contained Fluids

Imagine you have a fluid—a liquid or a gas—that is perfectly trapped inside a container without any air bubbles. This fluid isn’t just sitting there passively; it has a special rule governing how it handles any pressure you apply to it.

This rule states that when you apply a squeezing force (pressure) at any single point on a confined fluid that is not moving, this change in pressure is not absorbed in just that one spot. Instead, the fluid acts as a perfect messenger, transmitting that exact same pressure change to every other part of the container’s walls and to every single molecule within the fluid itself. The strength of this pressure is felt equally in all directions, throughout the entire system.

In its simplest terms: A push you give at one end is felt as an identical push everywhere else, instantly and without loss.

The Magic in Action: A Practical Example

The real power of this principle is how it allows us to multiply force. Think of a simple hydraulic car jack.

- It consists of two cylinders connected by a pipe and filled with oil. One cylinder has a small piston (let’s say 1 square centimeter), and the other has a large piston (say 100 square centimeters).

- When you push down on the small piston with a force equivalent to 1 kilogram, you are applying pressure to the oil.

- According to the principle, this exact same pressure is transmitted undiminished to the large piston.

- Here’s the transformation: The pressure (force per unit area) arriving at the large piston is the same, but because its area is 100 times larger, the total force it pushes upward with is 100 times greater.

So, your 1 kg of force on the small piston becomes 100 kg of lifting force on the large piston. You’ve traded a small movement over a long distance on your end for a massive force over a short distance on the other end. This is the secret behind hydraulic machinery like brakes, excavators, and presses, where a small input force is used to generate a tremendously powerful output.

Question 27.

Name two applications of Pascal’s law.

Ans:

1. Industrial Hydraulic Press for Molding Plastics

A primary application is found in large-scale industrial presses used for molding thermoplastics and composite materials. The system uses a confined fluid and two pistons of vastly different sizes. A comparatively small force applied to the small piston generates immense pressure in the fluid. According to Pascal’s law, this pressure is transmitted undiminished to a much larger piston. The large piston then exerts a massive, uniform force, pressing the raw plastic granules inside a mold. This ensures the material is compressed evenly into every detail of the mold cavity, creating consistently dense and intricately shaped plastic components.

2. Hydraulically-Adjustable Hospital Beds

The principle is crucial in the operation of hydraulically adjustable hospital beds. These beds use a network of fluid-filled cylinders connected by narrow pipes. When a caregiver activates a pump or control valve, it applies pressure to the fluid at one end of the system. This pressure transmits instantly throughout the confined fluid, as per Pascal’s law, causing pistons within the cylinders to extend or retract. This action smoothly and quietly lifts, lowers, or articulates different sections of the bed mattress. This allows for precise patient positioning for medical procedures, comfort, or safe entry and exit, all powered by the efficient transmission of fluid pressure.

Question 28.

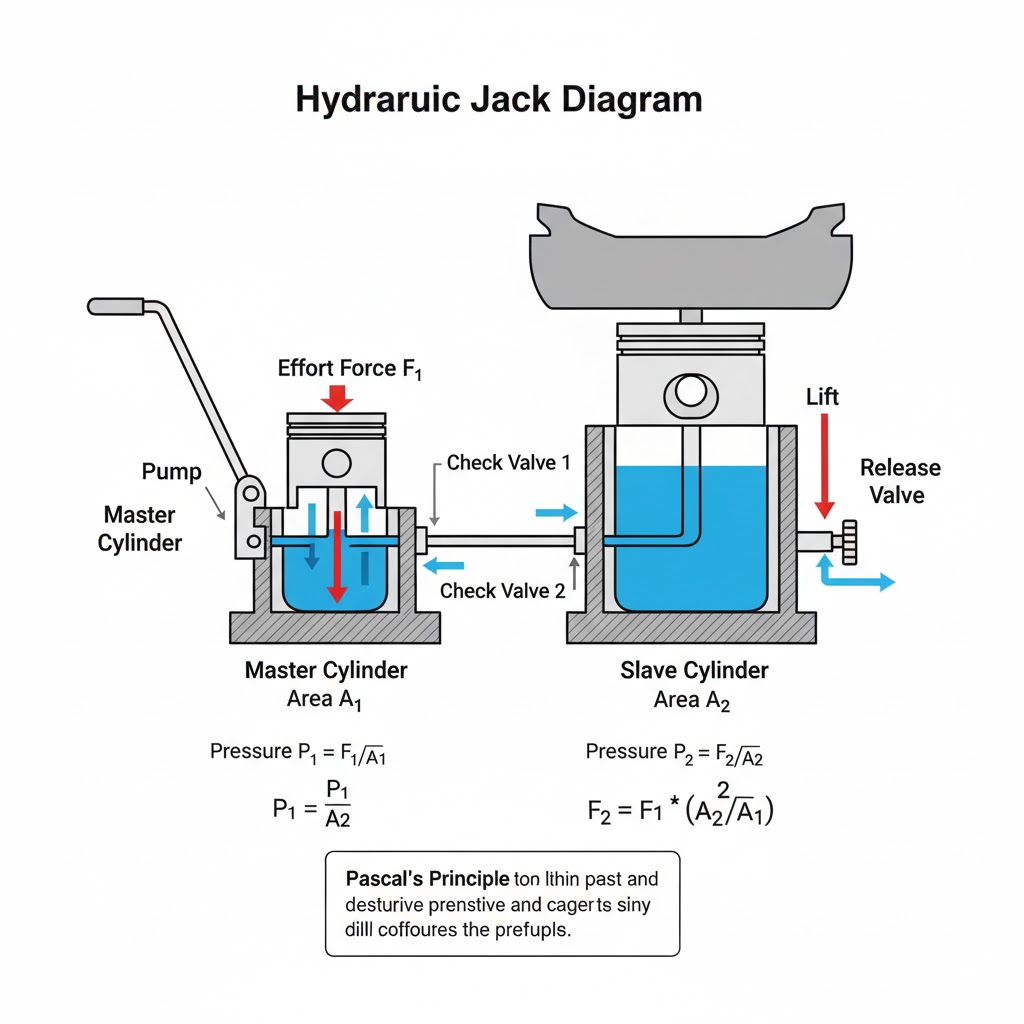

Explain the principle of a hydraulic machine. Name two devices which work on this principle.

Ans:

The Core Principle: Power Through Liquid Push

At its heart, a hydraulic machine works by using a liquid’s unique property to transfer and multiply force. Unlike air, a liquid is very difficult to squeeze into a smaller space; it is essentially incompressible. When you push on a liquid in a closed container, it doesn’t absorb the energy by compressing. Instead, it transmits that push, or pressure, equally and instantly in all directions.

Think of it like a water-filled balloon. If you press on one spot, the bulge and the pressure immediately move to another part of the balloon.

This is the key: A force applied to one part of a confined liquid shows up as pressure everywhere, allowing you to redirect that force to another location.

The Force Multiplier Effect

This is where the real power comes in. Most hydraulic machines use two pistons of different sizes, housed in connected cylinders filled with fluid.

- This creates pressure in the fluid.

- Because the pressure is the same everywhere, that same pressure now acts on a much larger piston.

- Since Force = Pressure x Area, the larger piston has a much larger area. With the same pressure, it generates a much larger output force.

It’s a trade-off: the larger piston will move a shorter distance than the smaller one, but it will do so with massively increased force. You are essentially trading “distance moved” for “power gained.”

Question 29.

Name and state the principle on which a hydraulic press works. Write one use of hydraulic press.

Ans:

The core idea behind every hydraulic press is a fundamental rule of fluid behavior known as Pascal’s Principle.

This principle explains that a liquid trapped in a sealed space does not compress easily. When you push on it by applying pressure at one point, that push travels undiminished through every part of the liquid. The fluid acts as a perfect messenger for force.

A hydraulic press puts this idea into practice with a simple yet powerful design. It uses two cylinders—one significantly wider than the other—linked together and filled with a sturdy oil. If you exert a modest force on the smaller piston, it creates pressure within the oil. Because the liquid cannot be squeezed into a smaller space, this same pressure is delivered entirely to the face of the larger, second piston.

Here is where the magic of scale happens. Pressure is defined as force spread over an area. The larger piston presents a much greater surface area for the fluid to push against. Since it experiences the same pressure as the small piston, the total upward force it can produce is multiplied dramatically. This mechanical advantage allows a person to generate a crushing force capable of bending steel.

A common industrial application of this power is in vehicle recycling yards. Hydraulic presses are the muscle behind car crushers, which efficiently flatten end-of-life automobiles into dense, stackable bundles of scrap metal, making transportation and processing far more efficient.

Question 30.

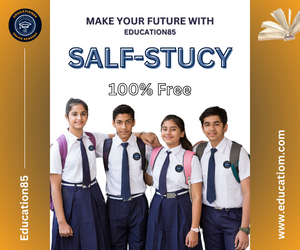

The diagram below in Fig. 4.12 shows a device which makes the use of the principle of transmission of pressure.

1. Name the parts labelled by the letters X and Y.

2. Describe what happens to valves A and B and to the quantity of water in the two cylinders when the lever arm is moved down.

3. Give reasons for what happens to valves A and B in part (ii).

4. What happens when the release valve is opened?

5. What happens to valve B in cylinder P when the lever arm is moved up?

6. Give a reason for your answer in part (v).

7. State one use of the above device.

Ans:

1. Name the parts labelled by the letters X and Y.

- X: Load Piston or Ram (the part that lifts the load in Cylinder Q).

- Y: Pump Piston (the part moved by the lever in Cylinder P).

2. Describe what happens to valves A and B and to the quantity of water in the two cylinders when the lever arm is moved down.

- Valve A: It opens.

- Valve B: It closes.

- Water in Cylinder P: Decreases, as it is forced out.

- Water in Cylinder Q: Increases, as water is forced into it from Cylinder P.

3. Give reasons for what happens to valves A and B in part (ii).

- The downward movement of the lever increases the pressure in Cylinder P.

- This high pressure forces Valve B to close (to prevent water from returning to the supply tank) and simultaneously forces Valve A to open, allowing the pressurized water to flow into Cylinder Q.

4. What happens when the release valve is opened?

- Opening the release valve provides a path for the pressurized water in Cylinder Q to escape back to the water supply tank.

- The pressure in Cylinder Q drops, and the weight of the load on the ram (X) pushes it down, forcing the water out and lowering the load.

5. What happens to valve B in cylinder P when the lever arm is moved up?

- Valve B opens.

6. Give a reason for your answer in part (v).

- Lifting the lever arm reduces the pressure in Cylinder P, creating a partial vacuum or low-pressure area.

- The higher pressure from the water supply tank pushes water up through the connector, forcing Valve B to open and fill Cylinder P with water. Valve A closes during this action to prevent water from flowing back from Cylinder Q.

7. State one use of the above device.

- The device is a hydraulic jack, used for lifting heavy objects, such as a car to change a tire.

Question 31.

Draw a simple diagram of a hydraulic jack and explain its working.

Ans:

The Mechanics of a Hydraulic Jack

A hydraulic jack is a masterclass in practical physics, transforming modest human effort into enough power to lift a vehicle. Its core operation is a cycle of building, transferring, and releasing pressure, all governed by a fundamental law of fluids.

The Core Principle: Force Multiplication

At the heart of the system is Pascal’s Principle, which states that pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted undiminished in every direction. The jack cleverly leverages this by using two different-sized pistons. The real trick lies in the relationship between Pressure, Force, and Area (P = F/A). While the pressure remains the same throughout the fluid, the force is a product of that pressure multiplied by the area it acts upon (F = P x A). A large surface area translates to a much greater output force from the same input pressure.

Stage 1: The Lifting Stroke (Building Power)

- User Action: You press the handle downward.

- Creating Pressure: This action drives the small pump piston inward, compressing the hydraulic oil trapped in its chamber. With the release valve sealed shut, the fluid has no escape route, causing its pressure to spike dramatically.

- Transferring Force: This highly pressurized oil is now forced through a passage into the main cylinder, directly underneath the much larger load piston (or ram).

- The Force Multiplier in Action: The same pressure now pushes upward against the massive surface area of the load piston. Because its area is many times larger than that of the pump piston, the resulting upward force is multiplied by a corresponding factor. This immense force lifts the heavy load.

- A Simple Comparison: Think of it as the reverse of a sharp needle. A needle concentrates a small force onto a tiny point to create extreme pressure for piercing. The hydraulic jack does the opposite: it takes a small force, uses it to create high pressure in a fluid, and then spreads that pressure over a large surface to generate a massive, lifting force.

Stage 2: The Reset Stroke (Preparing for the Next Lift)

- User Action: You pull the handle back up.

- Refilling the Pump: This retraction of the small pump piston creates a partial vacuum in the pump chamber. This drop in pressure causes a small inlet valve (a one-way gate) to open, drawing a fresh charge of oil from the reservoir into the chamber.

- Holding the Gain: Crucially, the main valve under the load piston stays shut during this process, locking the oil in the main cylinder and preventing the load from sinking. Each complete cycle of Stage 1 and 2 pushes a little more oil under the ram, raising the load incrementally with every pump.

Stage 3: The Controlled Descent (Lowering the Load)

- User Action: You gradually unscrew or open the release valve.

- Releasing the Pressure: This action creates an escape route for the trapped, high-pressure oil beneath the load piston, allowing it to flow back into the main fluid reservoir.

- Managing the Descent: As the oil evacuates, the pressure in the main cylinder drops. The weight of the load itself then pushes the ram downward, expelling the fluid. By carefully adjusting how much the release valve is open, you precisely control the flow of oil and, consequently, the speed at which the load is lowered, ensuring a smooth and safe descent.

In Essence

Fundamentally, a hydraulic jack is a trade-off. It exchanges a large, repeated movement of the small pump piston for a smaller, but immensely powerful, movement of the large load piston. Your repetitive effort is converted into fluid pressure, which the machine then translates back into a colossal mechanical force, making the impossible task of lifting a car as simple as pumping a handle.

Question 32.

Explain the working of a hydraulic brake with a simple labelled diagram.

Ans:

Here’s a simple labelled diagram of a hydraulic brake system:

Working of a Hydraulic Brake System:

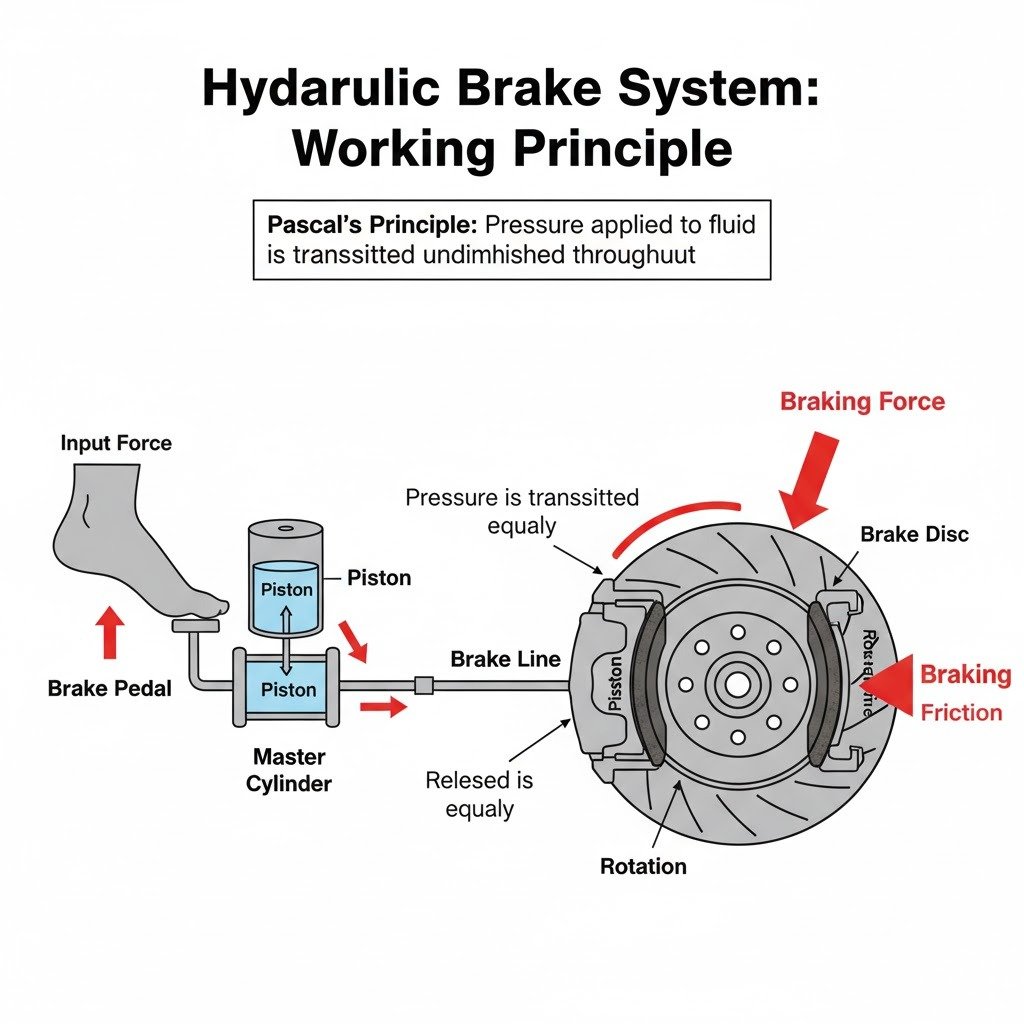

Hydraulic brakes also operate on Pascal’s Principle, allowing a small force applied by the driver to translate into a large braking force at the wheels.

- Brake Pedal and Master Cylinder: When the driver presses the brake pedal, this action pushes a piston within the master cylinder.

- Pressure Generation: This movement of the piston creates pressure in the brake fluid (an incompressible hydraulic fluid) contained within the master cylinder.

- Pressure Transmission: According to Pascal’s Principle, this pressure is transmitted equally and undiminished through the brake lines (tubes) to the individual slave cylinders located at each wheel.

- Braking at the Wheels:

- In a disc brake system (as shown in the diagram), the pressure from the fluid pushes pistons within the caliper.

- These caliper pistons then force the brake pads to clamp onto the rotating brake disc (rotor) attached to the wheel.

- The resulting friction between the pads and the disc generates a braking force that slows down and eventually stops the wheel.

- In drum brake systems, the pressure pushes brake shoes against the inside of a rotating drum.

- Releasing the Brakes: When the driver releases the brake pedal, the pressure in the system drops. Springs in the master cylinder and at the wheels pull the pistons and brake pads/shoes back to their original positions, disengaging the braking force.

This system ensures that even a moderate force on the brake pedal can effectively stop a heavy vehicle, as the pressure is multiplied by the larger surface area of the pistons in the slave cylinders compared to the master cylinder.

Question 33.

(a) Complete the following sentence : Pressure at a depth h in a liquid of density p is ………………….

(b) Complete the following sentence : Pressure is ……………….. in all directions about a point in a liquid.

(c)Complete the following sentence : Pressure at all points at the same depth is ………………..

(d) Complete the following sentence : Pressure at a point inside the liquid is …………………. To its depth.

(e)Complete the following sentence : Pressure of a liquid at a given depth is ……………… To the density of the liquid.

Ans:

(a) Complete the following sentence : Pressure at a depth h in a liquid of density p is h pg(where g is the acceleration due to gravity).

(b) Complete the following sentence : Pressure is equal in all directions about a point in a liquid.

(c) Complete the following sentence : Pressure at all points at the same depth is the same (or equal).

(d) Complete the following sentence : Pressure at a point inside the liquid is directly proportional to its depth.

(e) Complete the following sentence : Pressure of a liquid at a given depth is directly proportional to the density of the liquid.

Exercise 4 (A)

Question 1.

The S.I. unit of pressure is :

- N cm-2

- Pa

- N

- N m2

Question 2.

The pressure inside a liquid of density p at a depth h is :

- h ρ g

- ℎ /ρ𝑔

- ℎρ /𝑔

- ℎρ

Question 3.

The pressure P1 at a certain depth in river water and P2 at the same depth in sea water are related as :

- P1 > P2

- P1= P2

- P1 < P2

- P1 – P2 = atmospheric pressure

Question 4.

The pressure P1 at the top of a dam and P2 at a depth h form the top inside water (density p) are related as :

- P1 > P2

- P1 = P2

- P1 – P2 = h ρ g

- P2 – P1 = h ρ g

Exercise 4 (A)

Question 1.

A hammer exerts a force of 1.5 N on each of the two nails A and B. The area of the cross section of tip of nail A is 2 mm2 while that of nail B is 6 mm2. Calculate pressure on each nail in pascal.

Ans:

When a hammer drives a nail, the force it applies is only part of the story. The real difference comes from the nail’s tip. A smaller contact area results in a much more concentrated pressure, which is why sharp nails pierce wood so easily.

Let’s break down the problem. We know:

- Force on each nail, F = 1.5 N

- Cross-sectional area of nail A’s tip, A_A = 2 mm²

- Cross-sectional area of nail B’s tip, A_B = 6 mm²

Pressure (P) is calculated using the formula:

P = F / A

Since the pressure needs to be in pascals (Pa), and 1 pascal = 1 newton per square meter (N/m²), our first job is to convert the areas from mm² to m².

- 1 mm² = 1 × 10⁻⁶ m² (because 1 m = 1000 mm, so 1 m² = 1,000,000 mm²)

For Nail A:

- Area in m², A_A = 2 mm² = 2 × 10⁻⁶ m²

- Pressure, P_A = F / A_A = 1.5 N / (2 × 10⁻⁶ m²)

- P_A = 750,000 Pa or 7.5 × 10⁵ Pa

For Nail B:

- Area in m², A_B = 6 mm² = 6 × 10⁻⁶ m²

- Pressure, P_B = F / A_A = 1.5 N / (6 × 10⁻⁶ m²)

- P_B = 250,000 Pa or 2.5 × 10⁵ Pa

In Summary:

Even though the same force is applied to both nails, the pressure exerted on the wood is vastly different.

- The pressure under Nail A is 750,000 Pascals.

- The pressure under Nail B is 250,000 Pascals.

This demonstrates a key principle: for an equal force, pressure increases as surface area decreases. Nail A, with its finer point, experiences three times the pressure of Nail B, allowing it to penetrate materials with greater ease.

Question 2.

A block of iron of mass 7.5 kg and of dimensions 12 cm × 8 cm × 10 cm is kept on a table top on its base of side 12 cm × 8 cm.

Calculate: Thrust and Pressure exerted on the table top Take 1 kgf = 10 N.

Ans:

The thrust exerted by the iron block on the table top is equal to its weight. The mass of the block is 7.5 kg, and using the conversion 1 kgf = 10 N, the weight is calculated as follows:

Weight = mass × g = 7.5 kg × 10 N/kg = 75 N.

Thus, the thrust is 75 N.

The pressure exerted is the thrust per unit area. The base in contact with the table has dimensions 12 cm × 8 cm. Converting to meters: 12 cm = 0.12 m, 8 cm = 0.08 m. The area is:

Area = 0.12 m × 0.08 m = 0.0096 m².

Pressure = thrust / area = 75 N / 0.0096 m² = 7812.5 N/m² (or Pascals).

Therefore, the thrust is 75 N and the pressure is 7812.5 N/m².

Question 3.

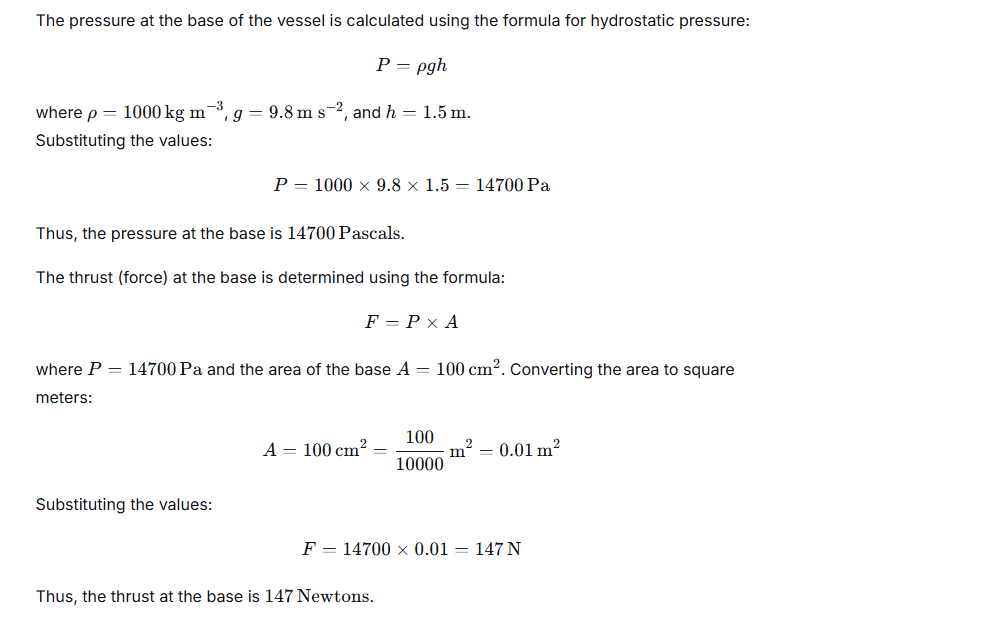

A vessel contains water up to a height of 1.5 m. Taking the density of water 103 kg m-3, acceleration due to gravity 9.8 m s-2 and area of base of the vessel 100 cm2, calculate: (a) the pressure and (b) the thrust at the base of the vessel.

Ans:

Question 4.

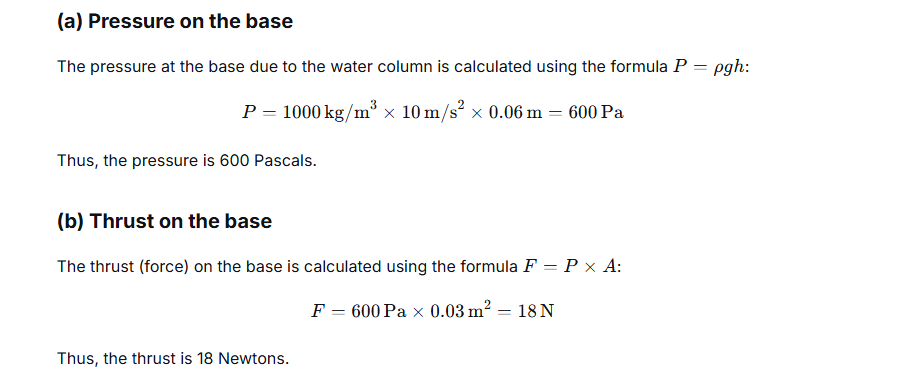

The area of base of a cylindrical vessel is 300 cm2. Water (density= 1000 kg m-3) is poured into it up to a depth of 6 cm. Calculate : (a) the pressure and (b) the thrust of water on the base. (g = 10m s-2.

Ans:

Question 5.

Calculate the height of a water column which will exert on its base the same pressure as the 70 cm column of mercury. The density of mercury is 13.6 g cm-3.

Will the height of the water column in part (a) change if the cross-section of the water column is made wider?

Ans:

(a) Calculating the Height of the Water Column

The pressure exerted by a liquid column depends on its height, density, and gravity, and is given by the formula:

Pressure, P = h ρ g

Where:

- h is the height of the liquid column.

- ρ (rho) is the density of the liquid.

- g is the acceleration due to gravity.

We are told that the pressure from the water column must equal the pressure from the mercury column. So, we can set their pressure equations equal to each other.

Pressure from Mercury = Pressure from Water

(h ρ g)_mercury = (h ρ g)_water

Since the acceleration due to gravity ‘g’ is the same for both, it cancels out from both sides of the equation.

(h_mercury × ρ_mercury) = (h_water × ρ_water)

Now we can plug in the values we know:

- h_mercury = 70 cm

- ρ_mercury = 13.6 g/cm³

- ρ_water = 1.0 g/cm³ (This is the standard density of water)

Calculation:

h_water = (h_mercury × ρ_mercury) / ρ_water

h_water = (70 cm × 13.6 g/cm³) / 1.0 g/cm³

h_water = 952 cm

Therefore, a water column of 952 cm will exert the same pressure on its base as a 70 cm column of mercury.

(b) Will the height change if the water column is made wider?

No, the height of the water column will not change if its cross-section is made wider.

Reasoning:

The pressure at the base of a liquid column is determined by the weight of the liquid directly above it per unit area. Making the column wider increases the total volume and total weight of the water.

However, it also increases the area of the base over which this total weight is distributed. These two effects—increased force and increased area—cancel each other out perfectly.

The formula P = h ρ g shows that pressure depends only on the height (‘h’) and the density (‘ρ’) of the liquid (and ‘g’, which is constant). It is completely independent of the shape or the cross-sectional area of the container. A wide column and a narrow column of the same liquid and the same height will always exert the same pressure at their base.

Question 6.

The pressure of water on the ground floor is 40,000 Pa and on the first floor is 10,000 Pa. Find the height of the first floor. (Take : density of water = 1000 kg m-3, g = 10 m s-2)

Ans:

Calculating Floor Height Using Water Pressure

The difference in water pressure measured on two floors of a building acts like a natural gauge for the vertical distance between them. In this scenario, the pressure drops from 40,000 Pascals on the ground floor to 10,000 Pascals on the first floor.

This means the weight of the water in the pipes between the two floors creates a pressure difference of:

30,000 Pascals

This number isn’t arbitrary; it is the direct result of the height of the water column. To find the height, we use the principle that the pressure from a fluid column is given by the product of its density, the force of gravity, and its height.

Setting up the relationship gives us:

Pressure Difference = (Density of Water) x (Gravity) x (Height Difference)

Plugging our known values into this equation looks like this:

30,000 = 1000 x 10 x Height Difference

Simplifying the multiplication on the right side gives us:

30,000 = 10,000 x Height Difference

To solve for the height, we simply rearrange the equation:

Height Difference = 30,000 / 10,000

This calculation provides a clear result:

Height Difference = 3 meters

In summary: The 30,000 Pascal pressure loss corresponds precisely to a 3-meter vertical climb of the water pipes from the ground floor to the first floor. This measurement reveals the functional height of the water column within the building’s structure, not necessarily the ceiling height.

Question 7.

A simple U tube contains mercury to the same level in both of its arms. If water is poured to a height of 13.6 cm in one arm, how much will be the rise in mercury level in the other arm?

Given : density of mercury = 13.6 x 103 kg m-3 and density of water = 103 kg m-3.

Ans:

When water is added to one arm of the U-tube, it disrupts the equilibrium because water is less dense than mercury. The system compensates for this by shifting the mercury levels. A key point to remember is that mercury is incompressible; the volume that drops in one arm must equal the volume that rises in the other. This means if the mercury level in the arm with water falls by a certain distance, the level in the clean arm will rise by that same distance. The total difference in height between the two mercury surfaces will therefore be twice that distance.

We can find this distance by comparing the pressures at the same horizontal level within the mercury, right at the interface where the two liquids meet. At this level in the arm containing water, the pressure is due to the weight of the 13.6 cm water column pushing down. In the other arm, the pressure at the same level is determined solely by the excess column of mercury.

For the system to be balanced, these two pressures must be equal. This gives us the relationship:

(Density of Water) × (Height of Water Column) = (Density of Mercury) × (Height Difference of Mercury)

We know the density of mercury is 13.6 times greater than that of water. Plugging this in:

(1) × (13.6 cm) = (13.6) × (Height Difference)

From this, we can see directly that the Height Difference of the mercury levels is 1.0 cm.

Since this total height difference of 1.0 cm is created by the mercury level dropping in one arm and rising in the other by equal amounts, we know that each change is half of this total. Therefore, the mercury level in the arm without water rises by 0.5 cm.

Question 8.

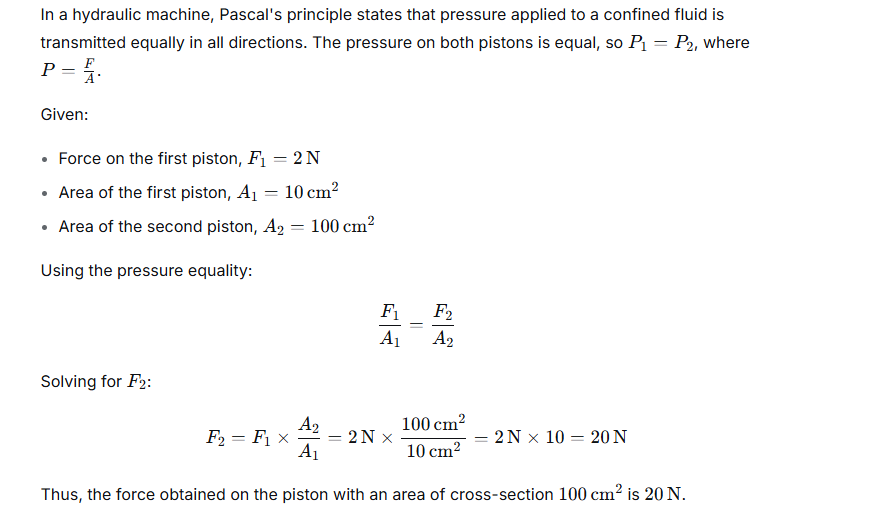

In a hydraulic machine, a force of 2 N is applied on the piston of area of cross section 10 cm2. What force is obtained on its piston of area of cross section 100 cm2 ?

Ans:

Question 9.

What should be the ratio of area of cross section of the master cylinder and wheel cylinder of a hydraulic brake so that a force of 15 N can be obtained at each of its brake shoes by exerting a force of 0.5 N on the pedal ?

Ans:

The operational principle of a hydraulic brake is a direct application of Pascal’s law, where a pressure change in an enclosed fluid is conveyed without reduction to every part of the fluid and the container walls. This ensures the pressure within the master cylinder (P_m) is identical to the pressure within the wheel cylinder (P_w), establishing the foundational equality P_m = P_w.

Since pressure is defined as force exerted per unit area (P = F/A), this equality can be expressed in terms of the forces and areas involved:

F_m / A_m = F_w / A_w

In this scenario, a modest input force (F_m) of 0.5 Newtons is applied to the master cylinder. This force is responsible for creating the initial pressure in the system. The task is to determine the output force (F_w) of 15 Newtons at the wheel cylinder, which acts directly on the brake shoe.

To find the necessary relationship between the cylinders’ cross-sectional areas, we rearrange the equation:

A_m / A_w = F_m / F_w

Substituting the given values:

A_m / A_w = 0.5 N / 15 N = 1/30

This calculation reveals that the cross-sectional area of the master cylinder is only one-thirtieth the size of the wheel cylinder’s area. This deliberate disproportion in area is the key to force multiplication, enabling a small input force at the brake pedal to generate a significantly larger output force at the brakes, effectively stopping the vehicle.

Question 10.

The areas of pistons in a hydraulic machine are 5 cm2 and 625 cm2. What force on the smaller piston will support a load of 1250 N on the larger piston? State any assumption which you make in your calculation.

Ans:

Analysis of the Hydraulic Force Multiplier

This hydraulic device operates on a straightforward yet powerful physical concept: a small force can balance a much larger one through the strategic use of pressure. The underlying rule is that within a confined liquid, pressure applied at one point is felt equally throughout the entire fluid.

The Governing Principle

The core idea can be summarized as follows: The pressure generated on the small piston must be equal to the pressure experienced by the large piston. Pressure is the amount of force spread over a given area.

This gives us the relationship:

Force on Small Piston / Area of Small Piston = Force on Large Piston / Area of Large Piston

Applying the Numbers

We are given:

- Target Load (F₂): 1250 N (the weight to be supported)

- Area of Large Piston (A₂): 625 cm²

- Area of Small Piston (A₁): 5 cm²

- Required Input Force (F₁): Unknown

To find the needed input force, we rearrange the principle:

F₁ = (F₂ × A₁) / A₂

Plugging in the values:

F₁ = (1250 N × 5 cm²) / 625 cm²

First, we multiply the top line: 1250 × 5 = 6250

Then, we divide by the area of the large piston: 6250 / 625 = 10

The Result

F₁ = 10 N

Interpreting the Outcome

This calculation reveals the machine’s remarkable efficiency. An input force of just 10 Newtons—which is about the force needed to lift a one-kilogram bag of sugar—is capable of supporting a massive 1250 Newton load, equivalent to about 125 kilograms.

This force multiplication comes with a trade-off. To displace a small amount of fluid in the large cylinder and lift the heavy load by a little, the small piston must be pushed down a much greater distance. The device essentially trades a large movement with a small force for a small movement with a large force.

A Practical Consideration

For this calculation to hold true in a real-world scenario, we must assume an ideal system. This means we ignore energy losses from friction between the moving parts and assume the hydraulic fluid does not compress at all. In practice, a slightly higher force might be needed to initiate movement and overcome these real-world inefficiencies.

This principle is the foundation for countless applications, most commonly the hydraulic jack used for lifting vehicles.

Question 11.

(i) The diameter of neck and bottom of a bottle are 2 cm and 10 cm, respectively. The bottle is completely filled with oil. If the cork in the neck is pressed in with a force of 1.2 kgf, what force is exerted on the bottom of the bottle?

(ii) Name the law/principle you have used to find the force in part (a).

Ans:

Analysis of Force in a Hydraulic System

(i) Determining the Force on the Bottom

The scenario describes a closed hydraulic system where a force applied to a small area creates a pressure that is harnessed to produce a larger force on a larger area.

Step 1: Establishing the System’s Pressure

A force of 1.2 kgf is applied to a cork fitted in the neck of the bottle. The neck has a diameter of 2 cm, meaning its radius is 1 cm. The area of the cork that transmits this force into the oil is calculated as:

*Area_cork = π × (radius)² = π × (1 cm)² = π cm²*

The pressure generated on the oil by this action is the force divided by this area:

*Pressure = Force_cork / Area_cork = 1.2 kgf / π cm²*

This pressure value, once created, propagates uniformly throughout the entire body of the confined oil.

Step 2: Calculating the Resulting Force at the Bottom

The bottom of the bottle has a much larger diameter of 10 cm, giving it a radius of 5 cm. Its surface area is therefore:

*Area_bottom = π × (radius)² = π × (5 cm)² = 25π cm²*

The force pushing upward on the bottom is the direct product of the transmitted pressure and this large area:

Force_bottom = Pressure × Area_bottom

Substituting the values we have:

*Force_bottom = (1.2 kgf / π cm²) × (25π cm²)*

The π terms cancel out, simplifying the calculation to:

*Force_bottom = 1.2 kgf × 25 = 30 kgf*

Conclusion: The force exerted on the bottom of the bottle is 30 kgf.

(ii) The Underlying Scientific Principle

This force multiplication is a direct application of Pascal’s Principle.

Pascal’s Principle states that a change in pressure applied to an enclosed, incompressible fluid is transmitted undiminished to every portion of the fluid and to the walls of its container.

In this case, the pressure created at the neck by the cork is identically transmitted to the bottom surface. Because the bottom has 25 times the area of the neck, the fluid pressure exerts a force that is 25 times greater at that point. The system essentially converts a modest input force into a powerful output force, demonstrating the core concept of a hydraulic multiplier. The constancy of pressure across different areas is the key to this phenomenon.

Question 12.

A force of 50 kgf is applied to the smaller piston of a hydraulic machine. Neglecting friction, find the force exerted on the large piston, if the diameters of the pistons are 5 cm and 25 cm respectively.

Ans:

The operating principle behind this hydraulic system is Pascal’s law, a fundamental concept in fluid mechanics. This law states that when pressure is applied to a fluid confined in an incompressible system, that pressure is transmitted with equal intensity in all directions. This means the pressure generated at one point will appear undiminished at every other point within the enclosed fluid.

In practical terms, pressure (P) is calculated as the amount of force (F) acting upon a given unit of area (A), expressed as P = F/A.

This relationship allows us to set up a powerful equivalence for a hydraulic system with two pistons:

The pressure created by the input force on the small piston equals the pressure experienced by the large piston.

This gives us the equation:

F₁ / A₁ = F₂ / A₂

Where:

- F₁ is the 50 kgf input force applied to the smaller piston.

- A₁ is the surface area of the smaller piston.

- F₂ is the unknown output force on the larger piston (what we are solving for).

- A₂ is the surface area of the larger piston.

Since the pistons are circular, their effective areas are calculated using the formula for the area of a circle, A = πr². However, since we are given diameters, it is more direct to use A = πd²/4.

Step 1: Calculate the Piston Areas

- For the small piston (diameter = 5 cm):

A₁ = π × (5 cm)² / 4 = (25π)/4 cm² - For the large piston (diameter = 25 cm):

A₂ = π × (25 cm)² / 4 = (625π)/4 cm²

Step 2: Determine the Mechanical Advantage (Area Ratio)

The true force-multiplying capability of the system lies in the ratio of the two piston areas. The force is multiplied by this factor.

Area Ratio = A₂ / A₁ = (625π / 4) / (25π / 4)

Notice that the π and the 4 cancel out, simplifying beautifully to:

Area Ratio = 625 / 25 = 25

This result shows that the large piston has twenty-five times the surface area of the small piston.

Step 3: Calculate the Output Force

Because the pressure is equal throughout the fluid, the larger area results in a proportionally larger force. We can rearrange the original equation to solve for the output force:

F₂ = F₁ × (A₂ / A₁)

Substituting the known values:

F₂ = 50 kgf × 25

F₂ = 1250 kgf

Conclusion

Therefore, by applying a modest force of 50 kgf to the small piston, the system generates a significant force of 1250 kgf at the large piston. This demonstrates a mechanical advantage of 25, meaning the output force is twenty-five times greater than the input force. This core principle is what enables hydraulic jacks to lift vehicles and other massive objects with relative ease.

Question 13.

Two cylindrical vessels fitted with pistons A and B of area of cross-section 8 cm2 and 320 cm2 respectively are joined at their bottom by a tube and they are completely filled with water. When a mass of 4 kg is placed on piston A, Find: the pressure on piston A, the pressure on piston B, and the thrust on piston B.

Ans:

Understanding Force Multiplication in a Hydraulic System

This scenario is a classic demonstration of how a hydraulic system acts as a force multiplier, using a confined liquid to amplify an input force. The principle at work is that a liquid is largely incompressible, meaning pressure applied to it in one location must be transmitted equally to all other parts of the confined system.

From a Small Force to a System-Wide Pressure

The process begins with the 4 kg mass placed on the smaller piston (Piston A). The first step is to determine the force this mass exerts.

- The force (F_A) is the product of mass and gravitational acceleration: 4 kg multiplied by 9.8 m/s², which equals 39.2 Newtons (N).

This force is not acting in isolation; it is distributed over the surface area of Piston A.

- The area of Piston A is 8 cm², which is equivalent to 0.0008 m².

- Pressure is defined as force per unit area. Therefore, the pressure generated on the liquid by Piston A is calculated as 39.2 N divided by 0.0008 m², resulting in 49,000 Pascals (Pa).

This newly generated pressure of 49,000 Pa now fills the entire hydraulic system. Because the liquid cannot be compressed, this same pressure value acts uniformly on every surface in contact with the liquid, including the much larger Piston B.

Converting Pressure Back into an Amplified Force

While the pressure is identical throughout the system, the effect on Piston B is dramatically different due to its size. We now calculate the resulting thrust, or force, on Piston B.

- The area of Piston B is 320 cm², which is 0.032 m².

- Force is calculated by multiplying pressure by the area over which it acts.

- Therefore, the thrust on Piston B (F_B) is 49,000 Pa multiplied by 0.032 m².

This calculation gives a force of 1,568 N.

The Final Result in Perspective

To summarize:

- Pressure at Piston A: 49,000 Pa

- Pressure at Piston B: 49,000 Pa

- Thrust on Piston B: 1,568 N

The system demonstrates a key trade-off: the smaller piston moves a greater distance to displace enough fluid to make the larger piston move a smaller distance. However, in exchange for this reduced movement, the force is significantly multiplied. A modest 39.2 N input force is transformed into a powerful 1,568 N output thrust—enough to lift a heavy object. This is the fundamental mechanism behind equipment like hydraulic car jacks and industrial presses.

Question 14.

What force is applied on a piston of area of cross section 2 cm2 to obtain a force 150 N on the piston of area of cross section 12 cm2 in a hydraulic machine?

Ans:

Exercise 4 (B)

Question 1.

What do you understand about atmospheric pressure?

Ans:

Our Invisible Ocean: Understanding Atmospheric Pressure