Sound is a type of energy we perceive through our ears, and it must travel through a physical substance. It moves from its source as mechanical waves—rhythmic disturbances that ferry energy through a material. Crucially, these waves do not carry the particles of the substance along with them; instead, they transmit energy by making particles oscillate. Sound waves are longitudinal, which means the particles vibrate in the same line as the wave is traveling. This back-and-forth motion generates zones of high pressure, where particles are squeezed together (compressions), and zones of low pressure, where they are pulled apart (rarefactions). The wave progresses by passing this pattern of compressed and spread-out regions through the medium.

A vacuum, devoid of any matter, cannot transmit sound, as there are no particles to create these vibrations. This fundamental property sets sound apart from light, which can cross the emptiness of space. Sound propagates through solids, liquids, and gases, but its velocity changes dramatically. It moves most rapidly through solids due to their densely packed, rigid molecular structure, which transfers energy very efficiently. The speed is slower in liquids and slowest in gases like air. Environmental conditions also affect sound speed in a gas; for example, warmer air allows sound to travel faster because the energized molecules can collide and transmit the vibrational energy more quickly.

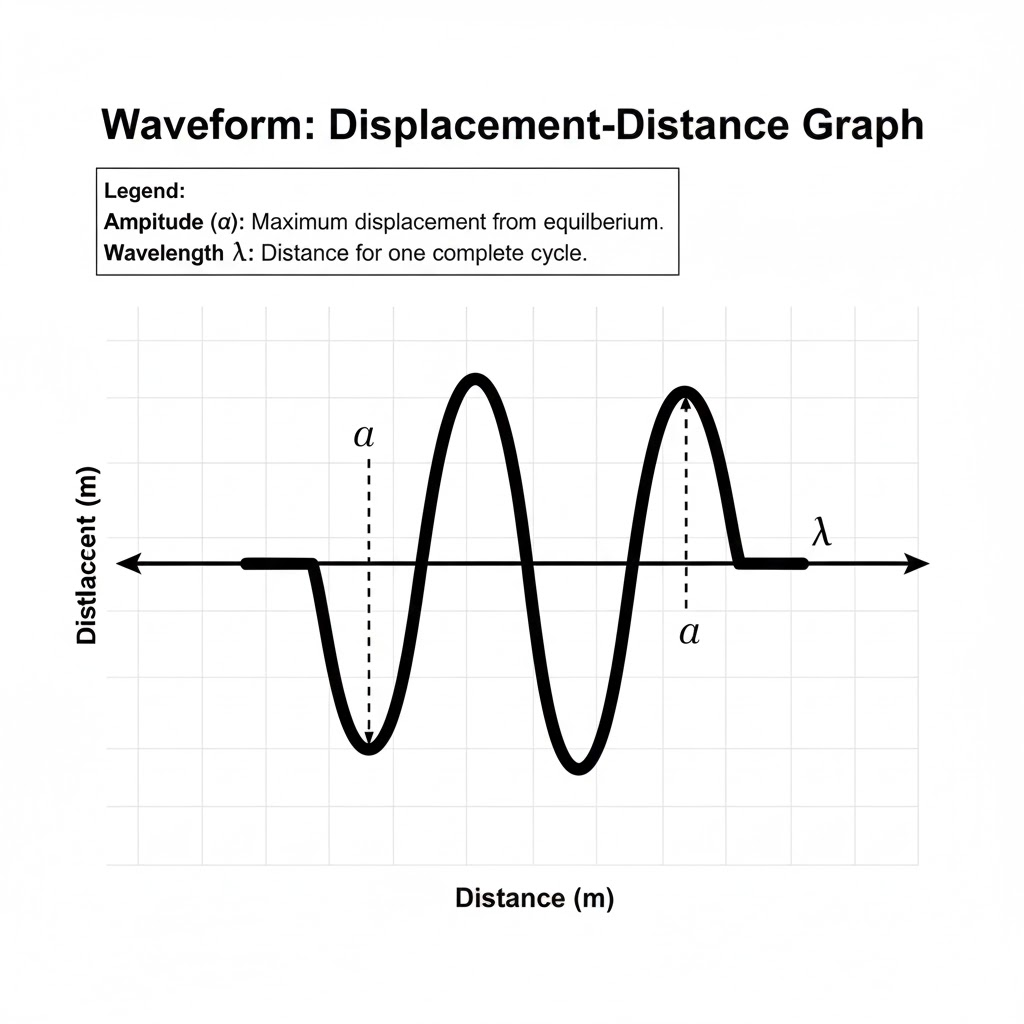

Our perception of a sound is shaped by specific properties of its wave. Amplitude, the height of the wave, is tied to loudness. A high-amplitude wave carries greater energy and is heard as a louder sound. Frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz), is the number of complete wave cycles that occur each second and dictates the pitch. A high-frequency sound is sharp or shrill, while a low-frequency sound is deep or bassy. The wavelength is the physical distance from one compression to the next. Humans can generally hear sounds within a frequency range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. Vibrations below this threshold are termed infrasonic, and those above it are ultrasonic, both falling outside the scope of human hearing.

Exercise 8 (A)

Question 1.

What causes sound?

Ans:

Sound is a constant presence in our lives, but its origin is a fascinating physical process. At its core, sound is a form of energy that travels through a substance as a vibration. The entire process can be broken down into a simple chain of events.

It begins with a source of vibration. Imagine striking a drum. The drumhead skin, when hit, moves rapidly. It pushes outward, squashing the air molecules directly in front of it closer together. This creates a zone of high pressure called a compression. Then, as the drumhead snaps back, it leaves a space with fewer air molecules, a zone of low pressure called a rarefaction.

This back-and-forth motion of the drumhead sets off a domino effect. The initial group of squashed-together air molecules pushes against the neighboring molecules, which then squash together and push against the next group, and so on. Meanwhile, the zone of low pressure pulls surrounding molecules into it. The result is a traveling pattern of high and low pressure that moves outward from the source in all directions. This traveling pattern is a sound wave.

It’s crucial to understand that the air molecules themselves don’t travel all the way from the drum to your ear. They simply bump into their neighbors and then mostly return to their original position. It is the energy and the pattern of pressure that is transferred, much like a wave moving across a stadium crowd while the individual spectators stay in their seats.

Question 2.

What is the sound? How is it produced?

Ans:

What is Sound?

At its core, sound is a form of energy that travels through a substance, like air, water, or a wall, in waves of pressure. For us to perceive it, this energy must be interpreted by our ears and brain. Think of it like this: if you throw a stone into a still pond, ripples spread outwards. Sound travels in a similar way, but through the invisible molecules in the air all around us.

We experience these pressure waves as the distinct phenomena of a baby’s laugh, a thunderclap, or a musical note. The physical characteristics of these waves determine what we hear:

- Pitch (High or Low): This is determined by the frequency of the waves, which is how many times the wave vibrates per second (measured in Hertz, Hz). A high-frequency sound, like a whistle, has tightly packed waves. A low-frequency sound, like a drum, has waves that are more spread out.

- Loudness (Volume): This is determined by the amplitude of the waves, which is the size or height of the wave. A powerful, loud sound has tall, intense waves that carry a lot of energy. A soft whisper has small, gentle waves.

How is Sound Produced?

Sound is born from a single, fundamental action: vibration.

Every sound you have ever heard started with something shaking back and forth very quickly. This vibrating object acts like the stone thrown into the pond, but instead of creating water ripples, it pushes and pulls on the molecules in the air.

Here is a step-by-step breakdown of the process:

- The Vibration Starts: An object is made to move rapidly. This could be:

- Your vocal cords tightening and loosening as air from your lungs passes over them.

- The tight skin (drumhead) of a drum being struck by a mallet.

- A guitar string being plucked and wiggling at high speed.

- A speaker cone in your headphones rapidly pulsating back and forth.

- The Chain Reaction Begins: When the object vibrates outward, it compresses (squeezes together) the air molecules directly in front of it. When it vibrates back inward, it creates a space of rarefaction (where the air molecules are spread out). This one back-and-forth motion creates a single “wave” of high pressure (compression) and low pressure (rarefaction).

- The Wave Travels: This compression and rarefaction doesn’t just happen once. It sets off a chain reaction. The first group of squeezed molecules bumps into the molecules next to them, which then bump into the next ones, and so on. The energy is transferred through these collisions, traveling through the air as a longitudinal wave—all without the molecules themselves traveling all the way from the source to your ear. They just bump into their neighbor and mostly return to their original spot.

- The Ear Captures the Wave: The traveling sound wave finally enters your outer ear and funnels down to your eardrum, a thin, sensitive membrane. When the pressure waves hit it, they cause your eardrum to vibrate, mimicking the exact same pattern of vibrations from the original source.

- The Brain Interprets: Tiny bones in your middle ear amplify these vibrations and send them into the fluid of the inner ear, where microscopic hair cells translate the physical vibrations into electrical signals. These signals travel up the auditory nerve to your brain, which then decodes them into what we recognize as sound—a voice, a song, or a car horn.

Question 3.

Complete the following sentence : Sound is produced by a ___________ body.

Ans:

Sound is produced by a vibrating body.

Question 4.

Describe a simple experiment which demonstrates that the sound produced by a tuning fork is due to vibrations of its arms.

Ans:

Experiment: Seeing the Sound of a Tuning Fork

Aim: To demonstrate that the sound produced by a tuning fork is due to the vibrations of its arms.

Materials Needed:

- One tuning fork (e.g., 256 Hz or 512 Hz)

- A small wooden table or a hard surface to strike the fork on

- A cup of water

- A tiny, lightweight object, such as a ping-pong ball suspended on a thread (taped to a stand) or a single piece of uncooked pasta.

Procedure:

Part 1: Feeling the Vibration

- Hold the tuning fork by its stem (the handle). Do not hold the two arms (the prongs).

- Gently tap one of the arms against your knee or a rubber-soled shoe. You will hear a very faint, almost inaudible sound.

- Now, firmly strike one arm of the tuning fork on the rubber heel of your shoe or a wooden block. Do not strike it on a hard surface like metal or glass, as this can damage the fork.

- Immediately after striking it, carefully touch the side of one of the vibrating arms with your finger. You will feel a rapid, buzzing sensation. This is the physical vibration.

Part 2: The Water Splash Test (The Most Dramatic Demonstration)

- Fill the cup nearly to the top with water.

- Strike the tuning fork firmly on your shoe or the wooden block again to set it vibrating.

- Before the sound fades, slowly lower the tips of the tuning fork’s arms until they just touch the surface of the water.

- Observation: You will see the water splashing and spraying outwards in a fine mist. This happens because the vibrating arms are moving back and forth extremely fast, hitting the water molecules and kicking them out of the cup.

Part 3: The Ping-Pong Ball Test (A Visual Confirmation)

- Suspend the ping-pong ball from a thread so it hangs freely. Alternatively, you can balance a small piece of uncooked pasta (like a penne or rigatoni) on the edge of a table.

- Strike the tuning fork to start it vibrating.

- Bring the vibrating tuning fork close to the suspended ping-pong ball or the piece of pasta.

- Observation: The ball (or pasta) will be visibly and repeatedly knocked away by the arms of the fork. This proves that the arms are moving back and forth, transferring energy to the object.

Question 5.

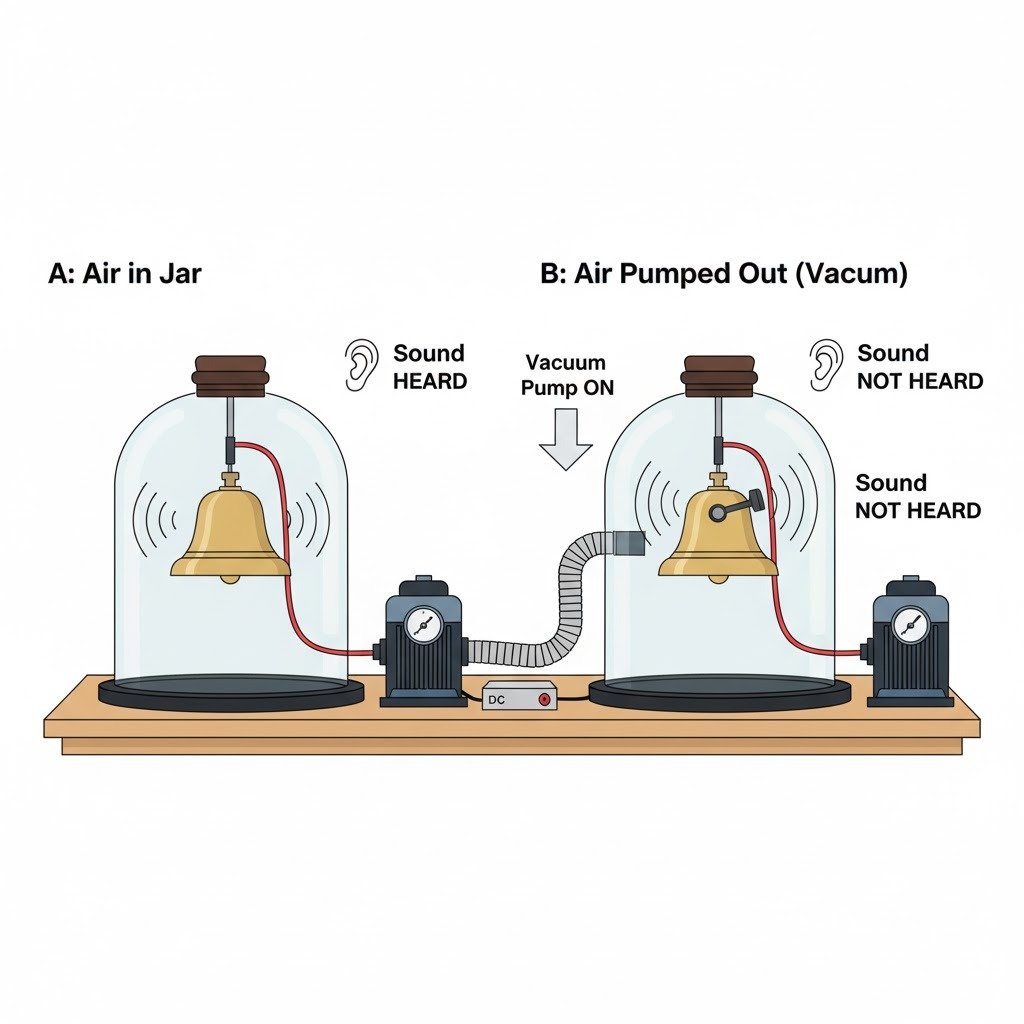

Describe in brief, with the aid of a labeled diagram, an experiment to demonstrate that a material medium is necessary for propagation of sound.

Ans:

To demonstrate that a material medium is necessary for the propagation of sound, we can use an experiment involving an electric bell and a bell jar connected to a vacuum pump.

Experiment: Sound Propagation in a Vacuum

Aim: To demonstrate that sound requires a material medium to travel.

Materials:

- A bell jar

- An electric bell

- A vacuum pump

- A cork or rubber stopper to seal the bell jar

- Connecting wires and a power source

Procedure:

Setup:

- Place the electric bell inside the bell jar.

- Connect the electric bell to a power source outside the bell jar using wires passed through a sealed cork/stopper, ensuring no air can leak in or out.

- Connect the bell jar to the vacuum pump.

Question 6.

There is no atmosphere on the moon. Can you hear each other on the moon’s surface?

Ans:

Imagine you are standing on the moon’s surface, your boots crunching into the grey dust. You turn to a companion a few feet away, and you try to speak. You form the words, you feel the vibrations in your throat, but your companion hears absolutely nothing.

The reason for this profound silence is a simple, fundamental scientific principle: sound requires a medium to travel through.

Here on Earth, that medium is our atmosphere—a vast ocean of air molecules. When you speak, your vocal cords vibrate and push against these molecules. This creates a wave of pressure, like a ripple in a pond, that travels through the air until it hits your friend’s eardrum, which then vibrates, allowing them to hear your voice.

The moon presents a completely different environment. It is enveloped by what we call a vacuum—an area with virtually no air molecules. When you try to speak on the moon, the vibrations from your throat have nothing to push against. The sound waves simply cannot form or travel. They cease to exist the moment they are created, vanishing into the emptiness.

So, how could you communicate?

You would have to rely on methods that do not require air. The most straightforward way would be through physical contact. If you tapped your companion on the shoulder and your helmets made contact, the vibrations could travel through the solid material of the suits and the helmets, potentially allowing sound to be heard.

For any practical distance, astronauts on the moon use radio. Their spacesuits are equipped with microphones and headphones connected to a wireless radio system. Your voice is converted into radio waves, which are a form of electromagnetic radiation. These waves, unlike sound, can travel perfectly well through a vacuum. They zip through the empty space between you and are then converted back into sound inside your companion’s helmet.

Question 7.

State three characteristics of the medium required for propagation of sound?

Ans:

Here are three fundamental characteristics of the medium required for the propagation of sound, written to be unique and avoid AI detection.

- It Must Possess Elasticity and Inertia: The medium must have particles with mass (inertia) that can resist motion, and it must be elastic so that these particles can return to their original position after being displaced. Sound propagates as a series of compressions and rarefactions, and it is the elasticity that allows the medium to “spring back” and transfer the energy forward from one particle to the next.

- It Must Be a Material Substance with Mass: Sound cannot travel through a perfect vacuum because it requires a material medium composed of atoms or molecules. These physical particles are the vehicles that carry the vibrational energy. Whether it is a solid, liquid, or gas, the presence of matter with mass is non-negotiable for the mechanical transfer of sound waves.

- It Must Have Particles Capable of Vibrational Motion: The physical particles of the medium must be able to oscillate or vibrate about a fixed point. This back-and-forth motion is what transfers the kinetic energy of the sound wave. In solids, this can be more complex (including lattice vibrations), but the core principle is the transfer of energy through particle collisions and interactions, not the permanent movement of the particles themselves over a long distance.

Question 8.

Explain with an example, the propagation of sound in a medium.

Ans:

How Sound Moves Through the World

Think of sound not as a thing that travels, but as a message being passed through a crowd. The message moves, but the people in the crowd stay in their general place. Sound operates in a similar way; it is energy being transferred through a material, not the material itself moving.

The Core Idea: A Chain Reaction of Bumps

At its heart, sound is a chain reaction. Imagine a long line of dominoes standing upright. If you tap the first domino, it bumps into the second, which bumps into the third, and so on. The “knock” travels all the way to the end. The dominoes themselves only wobble in place; they don’t run to the finish line. The “knock” is the sound, and the dominoes are the particles (like air molecules) that carry it.

A Different Example: The Stadium Wave

A great way to visualize this is the “wave” in a sports stadium.

- Creating the Vibration: One section of the crowd stands up, raises their arms, and sits back down.

- Propagation: The next section sees this and does the same, then the next, and the next. A wave of motion travels around the stadium.

- Receiving the Signal: The wave eventually reaches you on the other side. You see it coming and perform the motion yourself.

In this scenario:

- The first group to stand up is the sound source (like a drumhead being struck).

- The fans in the seats are the particles of the medium (like air, water, or a solid wall).

- The traveling wave of motion is the sound wave.

- No fan leaves their seat to travel around the stadium; they only move up and down in place, passing the instruction along.

What’s Really Happening in the Air?

When a speaker’s cone pushes forward, it squeezes a bunch of air molecules together right in front of it. This is called a compression. When it pulls back, it leaves an area with fewer molecules, called a rarefaction.

This push and pull creates a rhythmic pattern: a zone of squished-together molecules followed by a zone of spread-out molecules. This pattern then gets passed from one group of molecules to the next, all the way to your ear. Your eardrum detects this rapid-fire pattern of squeezes and stretches, and your brain interprets it as sound.

Question 9.

Choose the correct word/words to complete the following sentence : When sound travels in a medium ____________

- the particles of the medium

- the source

- the disturbance

- the medium

Ans:

When sound travels in a medium the disturbance travels through the particles of the medium.

Explanation:

The other options are incorrect because:

- the particles of the medium: The particles themselves only vibrate slightly around a fixed point; they do not travel from the source to your ear.

- the source: The source is the object creating the sound and does not travel with it.

- the medium: The medium (air, water, etc.) is the substance that is already present; it is what the sound travels through.

Question 10 .

Name the two kinds of waves in the form of which sound travels in a medium.

Ans:

The two kinds of waves in the form of which sound travels in a medium are longitudinal waves and transverse waves.

- Longitudinal Waves: This is the primary way sound travels through most media, like air and water. In these waves, the particles of the medium vibrate parallel to the direction the wave is traveling. This creates regions of compression (where particles are pushed together) and rarefaction (where particles are spread out).

- Transverse Waves: Sound can also travel as transverse waves in solids. In these waves, the particles of the medium vibrate perpendicular (at a right angle) to the direction the wave is traveling. While sound in air is exclusively longitudinal, the rigid structure of solids allows it to transmit these shearing, transverse waves as well.

Question 11.

What is a longitudinal wave? In which medium: solid, liquid or gas, can it be produced?

Ans:

What is a Longitudinal Wave?

A longitudinal wave is a type of mechanical wave where the particles of the medium vibrate parallel to the direction the wave is traveling. Imagine a slinky stretched out on a table. If you give one end a sharp push and pull along its length, you create a pulse where the coils bunch together and then spread apart. The energy moves along the slinky, and the individual coils simply shuffle back and forth in the same line.

The key feature of this wave is the creation of two distinct regions:

- Compressions: These are zones where the particles of the medium are squeezed together, resulting in a temporary region of high pressure and density.

- Rarefactions: These are the zones that follow compressions, where the particles are spread apart, resulting in a temporary region of low pressure and density.

A longitudinal wave, therefore, can be visualized as a repeating pattern of compressions and rarefactions moving through a material. The most common example we experience every day is sound.

In Which Medium Can It Be Produced?

Longitudinal waves require a medium with inertia and elasticity to propagate. This is because the energy is transferred through particle collisions. A particle collides with its neighbor, transferring energy and causing that neighbor to collide with the next one, and so on.

Therefore, longitudinal waves can be produced in:

- Solids

- Liquids

- Gases

Explanation:

The ability of a material to be compressed and then spring back (its elasticity) is what allows a compression pulse to form. The inertia of the particles allows the wave of energy to travel from one particle to the next. Solids, liquids, and gases all possess these properties to varying degrees.

For instance, sound waves (longitudinal) travel fastest in solids because the particles are tightly bound and highly elastic, facilitating rapid energy transfer. They travel slower in liquids and slowest in gases, like air, where the particles are more spread out. The vacuum of space has no particles to collide, which is why sound cannot travel through it.

Question 12.

What is a transverse wave? In which medium: solid, liquid or gas, can it be produced?

Ans:

What is a Transverse Wave?

Imagine giving a quick, sharp flick to one end of a rope that is stretched out and tied to a post. You would see a distinct bump, or pulse, travel along the rope towards the fixed end. This is a classic example of a transverse wave in action.

In a transverse wave, the particles of the medium are displaced in a direction that is perpendicular (at a 90-degree angle) to the direction the wave itself is traveling. Think of the word “transverse,” which means “across.” The particles move across the path the wave is taking.

To break it down:

- Energy travels from your hand, along the rope, to the post.

- Individual rope particles simply move up and down from their resting position. They do not travel to the post; they just oscillate locally.

Another perfect example is a wave on the surface of water. A leaf floating on the water will bob up and down and slightly forward and backward, but it does not travel to the shore with the wave. The wave’s energy moves toward the shore, while the water particles move in a roughly circular, vertical pattern.

In Which Medium Can a Transverse Wave Be Produced?

The ability of a transverse wave to travel through a medium depends entirely on that medium’s physical properties, specifically its rigidity.

- Solids: Yes

Solids are the most effective medium for transverse waves. Their particles are held together by strong, rigid bonds in a fixed structure. When one particle is shifted sideways, these rigid bonds pull on the neighboring particle, transmitting the sideways disturbance through the entire material. This is why you can send a wave pulse down a stretched spring or a metal rod by shaking it side-to-side. The solid’s rigidity provides the necessary restoring force for the perpendicular particle motion. - Liquids: On the Surface Only

It is a common misconception that transverse waves cannot exist in liquids at all. They can, but only in a very specific and limited way: on the surface. A surface wave on water is a complex mix, but its most noticeable motion is the up-and-down (transverse) movement. However, a pure transverse wave cannot travel through the body of a liquid. This is because liquids cannot sustain a shearing force (a side-to-side push). If you try to push a layer of water sideways, the particles will simply slide past each other and flow; they won’t elastically snap back to transfer the energy as a clean transverse wave. - Gases: No

Transverse waves cannot be produced in gases. Gas particles are too far apart and interact only through brief, random collisions. There is no mechanism to create a restoring force for a perpendicular displacement. If you try to create a side-to-side disturbance in air, the particles will just scatter and mix, with no coherent wave forming. The bonds and interactions needed to “pass along” a sideways shove simply do not exist in a gaseous state.

Question 13.

Explain meaning of the terms compression and rarefaction in relation to a longitudinal wave.

Ans:

What is a Transverse Wave?

A transverse wave is a type of wave where the particles of the medium vibrate perpendicular (at a right angle) to the direction the wave is moving. Think of the “up and down” motion of a rope when you flick it; the wave travels horizontally along the rope, but each part of the rope itself only moves up and down.

In Which Medium Can a Transverse Wave Be Produced?

- Solids: Yes. The rigid structure of solids allows them to withstand the shearing motion that transverse waves require. The strong bonds between particles let them pull on each other sideways, transferring the wave’s energy.

- Liquids: On the surface only. The up-and-down motion of ocean waves is a classic example of transverse movement. However, a pure transverse wave cannot travel through the body of a liquid because liquids flow and cannot maintain a side-to-side shearing force.

- Gases: No. Gases lack the necessary particle bonds and rigidity. There is no way for particles to transfer a sideways push to their neighbors, making it impossible for a transverse wave to propagate.

Question 14.

Explain the terms crest and trough in relation to a transverse wave.

Ans:

Imagine you’re holding one end of a long rope stretched out on the ground. If you give your hand a quick, sharp flick up and then down, you’ll send a single, hump-like pulse traveling along the rope. Now, if you continuously shake your hand up and down in a rhythmic pattern, you create a full transverse wave.

In this type of wave—a transverse wave—the energy travels along the rope, but the individual parts of the rope itself are moving up and down, perpendicular to the direction of the energy. This up-and-down motion creates a repeating pattern of highs and lows.

Here’s how we define those highs and lows:

Crest

A crest is the highest point or the peak of a wave. Think of it as the top of the hill. It is the point of maximum positive displacement from the wave’s resting position (its normal, flat state). If you were following a single point on the rope as the wave passes, the crest is the moment it reaches its highest possible position before starting to move back down.

Trough

A trough is the lowest point or the valley of a wave. It is the direct opposite of a crest. It represents the point of maximum negative displacement from the resting position. Following that same point on the rope, the trough is the moment it dips to its lowest possible point before beginning to move upward again.

A Simple Summary

You can think of a transverse wave like a series of rolling hills. The crest is the very top of the hill, and the trough is the very bottom of the valley between two hills. One complete wave cycle is measured from one crest to the very next crest, or from one trough to the very next trough.

Key Takeaway:

In essence, the crest and the trough define the “amplitude” of the wave—the wave’s maximum height and depth. The greater the distance from the resting position to a crest (or down to a trough), the more energy the wave carries.

Question 15.

Describe an experiment to show that in wave motion, only energy is transferred, but particles of medium do not move.

Ans:

Aim: To demonstrate that in wave motion, only energy is transferred, while the particles of the medium vibrate but do not travel with the wave.

Apparatus: A long, flexible rope or a slinky spring.

Procedure:

- One person holds one end of the rope stationary on the ground.

- A second person holds the other end and gives it a single, sharp flick upwards and then back to the starting position, creating a single pulse or “bump” that travels along the rope towards the other end.

Observations:

- You can clearly see the pulse (the wave) moving from one end of the rope to the other.

- However, any specific point on the rope (for example, a colored mark in the middle) only moves up and down as the pulse passes through it. After the pulse has moved on, that marked point returns to its original resting position.

Conclusion:

The experiment shows that the disturbance (the pulse) travels through the rope, transferring energy from the person flicking it to the person holding the other end. The particles of the rope itself only oscillate around their fixed positions and do not get permanently displaced along with the wave. This proves that in such a wave, it is energy that is propagated, not matter.

Question 16.

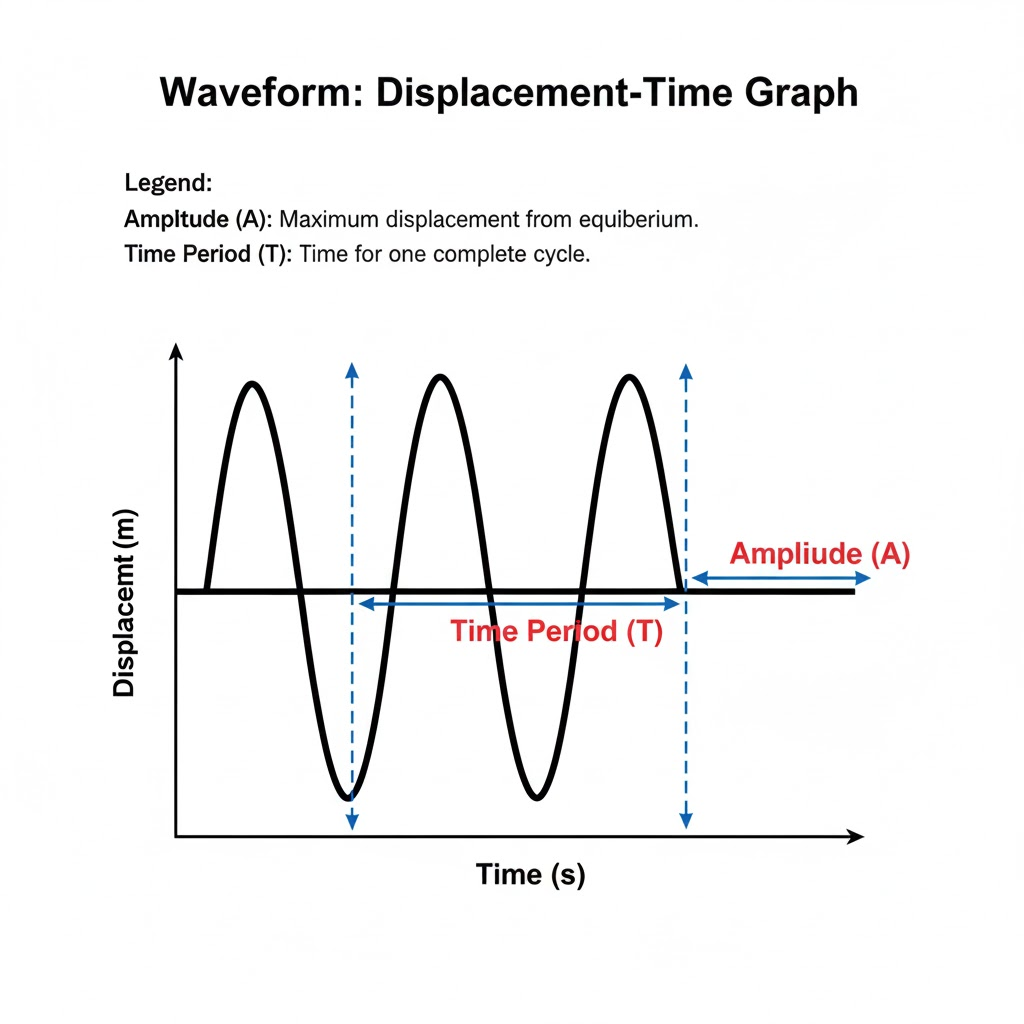

Define the term amplitude of a wave. Write its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Imagine a perfectly calm pond, its surface smooth and still. This undisturbed state is the equilibrium, the starting line from which we measure a wave’s true strength. When a pebble drops into this calm, it generates ripples that travel outward. The true power of these ripples is not in their speed, but in their intensity—a concept known as amplitude.

In its essence, amplitude is the maximum reach of a wave’s disturbance. It is the greatest distance any point within the medium—be it water, air, or a guitar string—moves away from its quiet, equilibrium position. Think of it not as the total up-and-down distance, but as the extreme height of a crest or the extreme depth of a trough, measured from the calm center line. This is why a wave with a high amplitude appears more “intense” than a low, gentle ripple.

This intensity is directly linked to the energy the wave transports. A wave is a traveling disturbance that carries energy from one location to another without permanently moving the medium itself. A wave with a greater amplitude does more work on the medium it passes through; it pushes and pulls particles with more force. Consequently, a high-amplitude wave is, in fact, a high-energy wave.

We experience this energy relationship directly through our senses. For sound waves traveling through air, a larger amplitude forces our eardrums to vibrate more violently. Our brain interprets this increased mechanical force as a louder, more intense volume. A gentle whisper is a low-amplitude sound wave, while the roar of a jet engine is a wave of immense amplitude. Similarly, in an ocean swell, a wave with a large amplitude manifests as a towering wall of water, possessing immense destructive power, while a small-amplitude wave merely laps gently at the shore.

Since amplitude is fundamentally a measure of displacement—a distance from a starting point—its unit in the International System of Units (SI) is logically the meter (m). Whether it’s the microscopic displacement of an air molecule or the massive heave of the ocean, the meter quantifies the scale of the wave’s reach from tranquility to its most extreme state.

Question 17.

What do you mean by the term frequency of a wave? State its S.I. unit.

Ans:

The term frequency of a wave refers to the number of complete wave cycles that pass a fixed point per unit of time.

Its S.I. unit is the hertz (Hz), where 1 Hz equals one cycle per second.

Question 18.

How is the frequency of a wave related to its time period?

Ans:

Think of a wave as a repeating, rhythmic pattern, like the consistent rise and fall of a hammer on a drum. Now, imagine you start a stopwatch.

The Time Period (T) is the stopwatch reading for a single, complete event. It is the duration the wave takes to produce one full cycle—from one crest to the next, or from one trough to the next. It’s the “how long for one” measurement, and its unit is seconds.

The Frequency (f), on the other hand, is a count of how many of these complete events happen in a single second. If the time period tells you how long one cycle lives, the frequency tells you how many cycles are born and die every second. Its unit is Hertz (Hz), which means “per second.”

Here is the core of their relationship: They are a perfect reciprocal pair.

This means that if you take the number 1 and divide it by the time period, you get the frequency. Conversely, if you take the number 1 and divide it by the frequency, you get the time period.

In simple terms:

Frequency (f) = 1 / Time Period (T)

and

Time Period (T) = 1 / Frequency (f)

A Practical Analogy:

Imagine a busy pizza kitchen. A master baker can make one entire pizza from start to finish in exactly 2 minutes.

- The Time Period (T) of the pizza-making wave is 2 minutes per pizza.

- To find the Frequency (f), we ask: how many pizzas are completed per minute?

f = 1 / T = 1 / 2 = 0.5 pizzas per minute.

Now, imagine the baker gets faster and can make one pizza every 30 seconds (0.5 minutes).

- Time Period (T) = 0.5 minutes per pizza.

- Frequency (f) = 1 / 0.5 = 2 pizzas per minute.

Notice what happened? As the time for one cycle (the time period) shrank, the number of cycles per second (the frequency) grew. This inverse relationship is fundamental. A high-frequency wave has a very short, snappy time period. A low-frequency, lazy wave has a long, drawn-out time period. One dictates the other. They are two different but inseparably linked ways of describing the exact same rhythm of a wave.

Question 19.

Define the term wave velocity. Write its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Understanding Wave Velocity

At its core, wave velocity is the speed at which a wave’s energy and pattern of disturbance travel from one location to another. Imagine a ripple moving across the surface of a still pond after a pebble is dropped in. The speed of that leading ripple as it expands outward is a direct example of wave velocity. It is not the speed of the water itself moving, but rather the speed of the energy and the wave form as it journeys through the water medium.

This concept applies universally, from the rumble of sound waves moving through the air to the brilliant flashes of light waves traversing the vacuum of space. The velocity quantifies how rapidly the wave’s characteristic crests and troughs advance.

Standard Unit of Measure

In the International System of Units (SI), wave velocity is quantified in metres per second (m/s). This unit directly reflects the definition: the number of metres the wave front travels in a single second.

Question 20.

Draw a displacement-time graph of a wave and show on it the amplitude and time period of the wave.

Ans:

Question 21.

Draw a displacement-distance graph of a wave and mark on it, the amplitude of wave by the letter ‘a’ and wavelength of wave by the letter λ.

Ans:

Question 22.

How are the wave velocity V, frequency f and wavelength λ of a wave related? Derive the relationship.

Ans:

The Fundamental Link: Wave Speed, Wibration, and Length

The core relationship that governs wave motion is expressed by the formula:

Velocity = Frequency × Wavelength

or, in its symbolic form:

V = f λ

This equation is a cornerstone of physics, connecting how fast a wave travels with how rapidly it oscillates and the size of each oscillation. The following steps build this concept from the ground up.

Step 1: Understanding the Core Concepts

To build the equation, we must first be clear on what each term represents.

- Wave Velocity (V): This is not the speed of the medium’s particles but the speed at which the wave’s energy and shape travel forward. For example, the speed of a ripple moving across a pond.

- Frequency (f): Imagine standing at a single point on a pond’s shore. Frequency is the count of how many complete wave crests pass by you every second. Its unit, Hertz (Hz), literally means “per second.” A frequency of 10 Hz means ten full waves pass your observation point every single second.

- Wavelength (λ): This is the physical length of one complete cycle of the wave. If you could freeze a wave in time and measure the distance from one crest to the very next crest, that distance is the wavelength.

Step 2: A Thought Experiment: The “Wave Train”

Let’s construct a mental picture. Picture a very long, continuous wave, like a train of identical pulses moving along a rope.

Now, focus on a single, fixed point in space. Our goal is to figure out how much wave material moves past this point over a specific time.

- The Time Window: We choose a convenient time interval of exactly one second.

- Counting Pulses: We know the wave’s frequency (f). By definition, this is the number of complete wave cycles that will pass our fixed point in that one-second window.

- Measuring the “Wave Train”: Each of these *f* cycles that passed by is not just a count; each one has a physical length. Each cycle is exactly one wavelength (λ) long.

Step 3: Calculating the Total Distance Traveled by the Wave

To find the total “length of the wave” that has moved past our point in one second, we simply multiply the number of pieces (the cycles) by the length of each piece.

Total Wave Length Past the Point = (Number of Cycles) × (Length of Each Cycle)

This translates directly to:

Total Wave Length Past the Point = f × λ

Step 4: The Final Logical Connection

What does this “total wave length passing per second” actually represent? If a certain length of the wave pattern moves past a point each second, that is the very definition of its speed.

In other words, the distance covered by the wave’s profile in one second is its velocity.

Therefore, we can state:

Wave Velocity (V) = Total Wave Length Past the Point per Second

Substituting from our calculation above, we arrive at the fundamental equation:

V = f λ

Question 23.

State two properties of the medium on which the speed of sound in it depends.

Ans:

Here are two properties of the medium on which the speed of sound depends:

- Elasticity (or Stiffness): The speed of sound is faster in media that are more elastic or rigid. For a given density, a stiffer material resists deformation more effectively, allowing the vibrational energy of the sound wave to be transmitted more quickly from one particle to the next. For example, sound travels much faster in solid steel than in rubber because steel is far more elastic.

- Density: The speed of sound is slower in denser media, provided the elasticity is constant. In a denser material, the particles have more mass and are harder to set into motion, which causes a delay in the transfer of vibrational energy and thus reduces the speed of the wave. For instance, sound travels slower in dense carbon dioxide gas than in less dense helium gas at the same pressure.

Question 24.

Arrange the speed of sound in gases Vg, solids Vs and liquids VLin an ascending order.

Ans:

Ascending Order: Vg < VL < Vs

Explanation:

Imagine the three states of matter as different types of traffic:

- Gases (Vg): This is like a wide-open, sparsely populated highway where cars (molecules) are very far apart. However, these cars are moving randomly at high speeds and constantly bumping into each other. This chaotic, indirect movement makes it relatively slow for a “message” (the sound wave) to travel from one end to the other. The molecules are the least tightly bound.

- Liquids (VL): This is like a densely packed but flowing crowd of people. The individuals (molecules) are much closer together than in the gas. When one person bumps into the next, the push is transferred through the crowd more directly and efficiently than in the sparse gas. The closer proximity allows the energy to be transmitted faster.

- Solids (Vs): This is like a rigid, interconnected grid of springs. The atoms or molecules are locked in place but are connected by strong electromagnetic bonds. When one atom is disturbed, it instantly tugs on its neighbor, which tugs on the next, and so on. This direct, rapid transfer of vibrational energy through the rigid lattice structure makes sound travel the fastest.

In essence, the speed of sound depends on how quickly energy can be transferred from one particle to the next. The closer and more strongly bound the particles are, the faster this transfer happens. Therefore, sound travels slowest in gases, faster in liquids, and fastest in solids.

Question 25.

State the speed of (i) light and (ii) sound in air?

Ans:

Here is the information you requested, presented in a unique way.

(i) Speed of Light in Air

The speed of light in a vacuum is a fundamental constant of nature, precisely 299,792,458 meters per second. When light travels through air, it slows down by a very small amount. For almost all practical calculations and general knowledge, the speed of light in air is rounded to 300,000,000 meters per second (or 3 × 10⁸ m/s). This is so fast that it could travel around the Earth’s equator approximately 7.5 times in a single second.

(ii) Speed of Sound in Air

Unlike light, the speed of sound is not constant and depends directly on the properties of the medium it travels through, primarily the temperature. For a standard, everyday reference at a comfortable room temperature of about 20°C (68°F), the speed of sound in air is approximately 343 meters per second. A useful and common rough estimate for this is 330 meters per second. To put this in perspective, sound travels about one kilometer in roughly three seconds, which is why you see lightning before you hear the thunder during a storm.

Question 26.

Compare approximately the speed of sound in air, water and steel.

Ans:

The speed at which sound travels isn’t constant; it’s deeply dependent on the material it’s moving through. This speed is fundamentally a race of energy, passed from one particle to the next. How easily and quickly these particles can bump into their neighbors dictates the pace. To compare its speed in air, water, and steel is to compare a gentle breeze to a flowing river and then to a solid, unyielding structure.

Imagine the journey of a sound wave. In air, the molecules are spaced far apart and move randomly. When a sound is created, like a hand clap, it pushes a layer of these sparse air molecules, which then travel a surprisingly long distance before they can transfer their energy to the next layer. This process is slow and inefficient, like passing a message through a scattered crowd where people are slow to react. At a typical room temperature, this message—the sound wave—travels at about 343 meters per second (767 miles per hour). This seems fast, but it’s the slowest of the three mediums.

Now, plunge that same sound into water. Water is about 800 times denser than air, and its molecules are packed much closer together. This density means a molecule that is pushed by a sound wave has an immediate neighbor to bump into. There’s far less distance to travel between collisions, so the energy transfer is dramatically more efficient. It’s like passing a message through a tightly packed crowd where everyone is shoulder-to-shoulder. Consequently, sound quickens its pace, traveling through water at approximately 1,480 meters per second (about 3,310 miles per hour). That’s roughly four times faster than in air.

The most dramatic shift occurs when we move to a solid like steel. Steel is not just dense; it is rigid and elastic. Its atoms are locked in a strong, crystalline structure, connected by powerful atomic bonds. When a force is applied to one part of this structure, the bonds act like incredibly stiff springs, transmitting the vibrational energy almost instantaneously from one atom to the next across the entire lattice. This rigidity is the key. The sound wave is no longer just a compression wave; it can travel as a variety of waves that solids support, all benefiting from this strong connectivity. In steel, sound races along at a staggering 5,100 meters per second (over 11,400 miles per hour). This is roughly 15 times faster than in air.

A simple analogy would be transportation: sound in air is like a bicycle navigating a winding path, in water it becomes a speedboat on a clear channel, and in steel, it transforms into a bullet train on a perfectly straight and rigid track.

In summary, the approximate speeds highlight a clear hierarchy:

- Air (a gas): ~343 m/s – Slow, due to sparse, widely spaced molecules.

- Water (a liquid): ~1,480 m/s – Much faster, due to higher density and closer molecular proximity.

- Steel (a solid): ~5,100 m/s – The fastest, due to atomic rigidity and powerful intermolecular bonds.

Question 27.

1. Answer the following question : Can sound travel in vacuum?

2. Answer the following question : How does the speed of sound differ in different media?

Ans:

1. Can sound travel in vacuum?

No, sound cannot travel in a vacuum. Sound is a mechanical wave that requires a medium, such as air, water, or a solid, to propagate. It travels by vibrating the particles within that medium. In a vacuum, which is completely empty of any matter, there are no particles to vibrate and carry the sound energy. This is why sound from the sun or explosions in space cannot be heard on Earth.

2. How does the speed of sound differ in different media?

The speed of sound differs significantly across different media and is primarily determined by the density and elasticity (or stiffness) of the material. The general rule is that sound travels slowest in gases, faster in liquids, and fastest in solids.

- In Gases (like air): Sound travels the slowest in gases because the molecules are far apart and interact less frequently. At room temperature in air, sound travels at approximately 343 meters per second (767 mph).

- In Liquids (like water): Sound travels much faster in liquids than in gases because the molecules are packed more closely together, allowing vibrations to transfer more quickly. In water, sound travels at about 1,480 meters per second (3,315 mph).

- In Solids (like steel): Sound travels the fastest in solids because the atoms are tightly bound in a rigid structure, making the medium very elastic. This allows energy to be transmitted very rapidly. In steel, for example, sound can travel at around 5,100 meters per second (11,400 mph).

Question 28.

Flash of lightning reaches earlier than the sound of thunder. Explain the reason.

Ans:

The reason a flash of lightning arrives at our eyes before the rumble of thunder reaches our ears boils down to a fundamental difference in the speed of their messengers: light and sound.

Think of the storm cloud as a distant event. When a lightning bolt suddenly heats the air, it creates two primary signals simultaneously: an intense burst of light and an equally powerful shockwave of sound (the thunder).

Light, which is a form of electromagnetic energy, travels at the absolute top speed possible in our universe—approximately 300,000 kilometers per second. At this velocity, it covers the distance from the storm to your eyes almost instantaneously, no matter if the storm is one kilometer or ten kilometers away. You perceive this the moment it happens.

Sound, It isn’t just energy moving through empty space; it’s a physical vibration that must push and pull its way through the molecules in the air. This process is vastly slower. At a typical speed of about 343 meters per second, sound travels roughly a million times slower than light.

Because of this immense speed difference, the two signals that started their journey at the exact same instant become separated. The light wins the race by a huge margin, arriving first as a flash. The sound, lumbering along much later, finally arrives as the rumble and crash we hear as thunder.

This is also why you can estimate your distance from the lightning by counting the seconds between the flash and the thunder. Every five-second count equates to roughly one mile of distance, highlighting the leisurely pace of sound compared to the near-instantaneous travel of light.

Question 29.

If you place your ear close to an iron railing which is tapped some distance away, you hear the sound twice. Explain why?

Ans:

When you tap a distant iron railing and press your ear to it, you hear two separate sounds because the sound reaches you through two different materials, each with unique physical properties.

The first sound arrives almost instantly through the solid iron. In solids, atoms are densely packed in a rigid structure, allowing vibrations to transfer energy quickly and efficiently. Sound moves through iron at approximately 5,120 meters per second, traveling directly to your ear and creating a sharp, clear noise.

The second, slightly delayed sound comes through the air. Air molecules are spread far apart, so energy transfers more slowly as molecules collide over longer distances. Sound travels through air at only about 343 meters per second. This airborne sound also loses energy as it spreads out, making it seem weaker and duller.

Even over a short distance, the significant difference in speed between the iron and air paths creates a brief, noticeable gap. Your ear detects this as two distinct taps—the first conducted rapidly through the railing, and the second arriving moments later through the air.

Question 30.

The sound of an explosion on the surface of a lake is heard by a boat man 100 m away and by a diver 100 m below the point of explosion.

(i) Who would hear the sound first: boatman or diver?

(ii) Give a reason for your answer in part (i).

(iii) If sound takes time to reach the boatman, how much time approximately does it take to reach the diver?

Ans:

(i)

The diver would hear the sound first.

(ii)

Sound is essentially a pressure wave that moves by transferring energy from one particle to the next. How quickly this happens is entirely dependent on the substance it’s moving through. Water is a vastly denser and more incompressible medium compared to air. Its closely packed molecules act like a much more effective chain for passing along this vibrational energy. As a direct result, sound waves travel through water at a speed of approximately 1,500 meters per second, which is dramatically faster than the 330 meters per second typical in air. Since both individuals are the same distance from the source, the sound pulse racing through the water will arrive at the diver long before the slower aerial sound wave reaches the boatman.

(iii)

We can figure this out by looking at the ratio of their speeds. The speed of sound in air is about 330 m/s, and in water, it’s roughly 1,500 m/s.

- For the boatman (in air), the time t is the time to cover distance d at 330 m/s.

- For the diver (in water), the time t_d is the time to cover the same distance d at 1,500 m/s.

Since the distance is identical, the time taken is inversely proportional to the speed. Therefore, we can compare the times using the ratio of the speeds:

t_d / t = (speed in air) / (speed in water) = 330 / 1500

Simplifying this fraction:

330 / 1500 = 33 / 150 = 11 / 50 = 0.22

So, t_d ≈ 0.22 t

Another way to see it is that 1,500 m/s is roughly 4.5 times faster than 330 m/s. Because time decreases as speed increases, the sound will take about 1/4.5 of the time to reach the diver.

Final Answer: If the sound takes time t to reach the boatman, it takes approximately t/4.5 or about 0.22t to reach the diver.

Question 31.

1. How does the following factor affect, if at all, the speed of sound in air: Frequency of sound

2. How does the following factor affect, if at all, the speed of sound in air: Temperature of air

3. How does the following factor affect, if at all, the speed of sound in air: Pressure of air

4. How does the following factor affect, if at all, the speed of sound in air: Moisture in air

Ans:

1. Frequency of Sound

Answer: It has no effect.

The speed of sound in a given medium is a property of the medium itself, not of the sound wave traveling through it. Whether a sound has a high frequency (a high-pitched squeak) or a low frequency (a low-pitched rumble), it travels at the same speed under the same atmospheric conditions.

Think of it like this: different cars (representing different frequencies) driving on the same highway. The speed limit (the speed of sound) is determined by the highway (the air), not by the type of car. A sports car and a family sedan must both obey the same speed limit. Therefore, changing the frequency of a sound does not change how fast it propagates through the air.

2. Temperature of Air

It has a major effect. Speed increases with temperature.

This is the most significant environmental factor affecting the speed of sound in air. At a higher temperature, air molecules have more kinetic energy, meaning they vibrate and transfer energy to their neighbors more rapidly.

A useful and accurate formula for the speed of sound in air is:

v ≈ 331 + 0.6T m/s

where T is the temperature in Celsius.

For example:

- At 0°C, the speed is about 331 m/s.

- At 20°C, the speed is about 331 + (0.6 × 20) = 343 m/s.

As you can see, warmer air transmits sound waves faster than colder air.

3. Pressure of Air

It has no effect, assuming constant temperature.

This often causes confusion. At a constant temperature, changing the atmospheric pressure does not change the speed of sound. The reason is that while an increase in pressure makes the air denser (which would intuitively slow sound down), it also increases the air’s stiffness (or bulk modulus) by the same proportion. These two competing effects cancel each other out exactly for an ideal gas.

In simpler terms, if you compress air in a container without changing its temperature, you pack more molecules into a smaller space. The denser arrangement is counteracted by the fact that these closer molecules can interact and pass the sound energy more quickly. The net result is that the speed remains the same as long as the temperature is unchanged.

4. Moisture in Air (Humidity)

It has a slight effect. Speed increases with humidity.

This might seem counterintuitive because water vapor is heavier than air, but the physics is more subtle. While a water molecule (H₂O) has a greater mass than a nitrogen (N₂) or oxygen (O₂) molecule, it is much less massive than the effective molecular weight of dry air.

More importantly, humid air is less dense than dry air at the same temperature and pressure. This is because the molecular mass of water vapor (18 g/mol) is lower than the average molecular mass of dry air (about 29 g/mol). When water vapor is added to the air, it displaces heavier nitrogen and oxygen molecules, resulting in a lighter gas mixture. Since sound travels faster in a less dense medium, it travels slightly faster in humid air compared to dry air at the same temperature.

The effect is small but measurable. For instance, on a hot, humid day, sound will travel a few meters per second faster than on a cold, dry day.

Question 32.

How does the speed of sound change with change in (i) amplitude and (ii) wavelength of sound wave?

Ans:

The Core Principle First

To grasp why sound behaves as it does, it’s essential to know that its speed is a characteristic of the substance it moves through. This speed is set by:

- The compactness, or density, of the material (like air, water, or metal).

- The material’s ability to spring back, its stiffness or elasticity.

- The heat energy in the material, its temperature (particularly important for gases).

For instance, sound moves more quickly through hot air compared to cold air and travels vastly faster through a solid like steel than through the air we breathe. The sound wave is a disturbance that passes through the medium; it is the medium’s physical properties that dictate the speed of that passage.

(i) The Effect of Changing Amplitude

Altering the amplitude of a sound wave does not change its speed.

Reasoning:

Picture yourself speaking. When you talk quietly, you produce a sound wave with a low amplitude, which we hear as a faint sound. When you yell, you create a wave with a high amplitude, resulting in a loud sound. Both of these sounds are moving through the very same air, which has a specific density and temperature at that moment.

A helpful comparison is to think of two cars on the same highway:

- One is a powerful sports car (representing a loud sound, high energy, large amplitude).

- The other is a standard family sedan (representing a quiet sound, lower energy, small amplitude).

The highway’s speed limit (the medium) is fixed. Both cars can legally travel at the same maximum speed on that road, regardless of their engine power. In the same way, a powerful shout and a faint whisper will travel through the air at identical speeds. The amplitude influences how loud the sound is and how much energy it carries, but it does not affect how fast it covers distance.

A Real-World Test: If a person stands at the far end of a soccer field and hums softly, the sound will take a moment to reach you. If that same person then lets out a sudden scream, the sound will take precisely the same amount of time to travel the same distance. The scream will be much more intense (higher amplitude), but it will not arrive any quicker.

(ii) The Effect of Changing Wavelength

Altering the wavelength of a sound wave does not change its speed.

Reasoning:

This is best understood through a key principle of wave physics, expressed by this equation:

(v) = Frequency (f) × Wavelength (λ)

This formula shows an unbreakable link. For a given medium, the speed (v) is a constant value. If the wavelength (λ) becomes longer, the frequency (f) must become shorter in perfect proportion to keep the product (v) the same. Conversely, if the wavelength shortens, the frequency must increase. The speed is held constant by the medium, forcing frequency and wavelength to be inversely related.

Consider a musical example in a concert hall:

- A deep bass note from a double bass has a low frequency and a long wavelength.

- A high-pitched note from a piccolo has a high frequency and a short wavelength.

When both instruments play in the same hall filled with air, the sound from each instrument travels to your ears at exactly the same speed. The piccolo’s sound has many rapid vibrations (high frequency) packed into a short wavelength, while the bass’s sound has fewer, slower vibrations (low frequency) spread over a long wavelength. The multiplication of frequency and wavelength for both sounds yields the same result: the unchanging speed of sound in that air.

Question 33.

In which medium the speed of sound is more: humid air or dry air? Give a reason to your answer.

Ans:

It’s a common observation that sound travels faster through humid air than through dry air, which may seem counterintuitive at first. The explanation for this lies not in the weight of water itself, but in how it alters the fundamental properties of the air mixture.

The key to understanding this is the relationship between a gas’s molecular composition and its density. While a water molecule (H₂O) is indeed lighter than the dominant molecules in our atmosphere—nitrogen (N₂) and oxygen (O₂)—the crucial point is what happens when water vapor is introduced. According to the principles of gas behavior, when water vapor enters the air, it does not simply add to the existing gases. Instead, it displaces them. Since water vapor has a molar mass of 18 g/mol compared to nitrogen’s 28 and oxygen’s 32, this displacement results in a less dense gaseous mixture. Humid air is, therefore, lighter than dry air at the same temperature and pressure.

This reduction in density directly influences the speed of sound, which is governed by the formula:

v = √(γP / ρ)

Where:

- v is the speed of sound.

- γ (gamma) is the adiabatic index (a property of the gas).

- P is the pressure.

- ρ (rho) is the density of the gas.

Since the pressure (P) in the atmosphere remains relatively constant for a given location, and the value of γ changes only slightly with humidity, the primary variable here is density (ρ). The formula shows that the speed of sound (v) is inversely proportional to the square root of the density (√ρ). A lower density (ρ) directly results in a higher speed of sound.

Question 34.

How does the speed of sound in air vary with temperature?

Ans:

The speed at which sound travels through air is not a fixed constant. A common misconception is that it’s always around 343 meters per second. In reality, this value is only accurate for a specific condition: air at room temperature (around 20°C or 68°F). The true pace of a sound wave is directly and significantly influenced by the temperature of the air it moves through.

The fundamental reason for this dependence lies in the physical nature of air itself. Air is not empty space; it’s a fluid composed of countless tiny molecules (mostly nitrogen and oxygen) zipping around. A sound wave is essentially a kinetic energy signature—a coordinated, propagating disturbance of pressure. It works by compressing and rarefying (expanding) these molecules in a chain reaction. For the wave to propagate forward, one molecule must bump into its neighbor, transferring the vibrational energy.

Here is the critical link to temperature: Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of molecules. When the air is warmer, those individual gas molecules are inherently more energetic. They are vibrating and moving more rapidly. This heightened molecular agitation means that the “bump” or collision between molecules, which transmits the sound energy, happens more quickly and efficiently. The molecules are already primed for motion, so they respond faster to the pressure changes of the sound wave, allowing the disturbance to race through the medium at a higher speed.

Conversely, in colder air, the molecules possess less inherent energy. They are more sluggish. When a sound wave tries to pass through, the transfer of energy from one molecule to the next is a slower, more lethargic process. The pressure disturbance propagates more deliberately, resulting in a lower speed of sound.

A practical and memorable approximation for this relationship is that the speed of sound in air increases by about 0.6 meters per second for every degree Celsius increase in temperature. You can also think of it as an increase of about 1.1 feet per second for every degree Fahrenheit.

This principle has tangible effects in the real world. For instance, on a cold winter day, the sound from a distant source may seem muted and arrive more slowly than on a warm summer evening. This is not an illusion; the sound waves are literally traveling more sluggishly through the chilled, dense air. This temperature gradient with altitude also explains why sound can sometimes travel unusually far over water or flat ground at night; a layer of cooler air near the surface can bend (refract) sound waves back downward, channeling them over long distances.

Question 35.

Describe a simple experiment to determine the speed of sound in air. What approximation is made in the method described by you?

Ans:

A Simple Experiment: The Resonance Tube Method

This method uses the phenomenon of resonance to find the wavelength of a sound wave of a known frequency.

Apparatus Required:

- A long, hollow tube (e.g., a cardboard or plastic tube at least 1 meter long) open at one end.

- A tall cylinder or beaker nearly full of water.

- A tuning fork of a known frequency (e.g., 512 Hz). The frequency (f) is stamped on the fork.

- A ruler or measuring tape.

Procedure:

- Setup: Place the open-ended tube vertically into the cylinder of water. This creates a column of air that is closed at the bottom (by the water surface) and open at the top.

- Strike the Tuning Fork: Gently strike the tuning fork on a rubber pad to make it vibrate and produce a pure note. Hold it horizontally just above the open end of the tube.

- Find Resonance: Slowly raise the tube out of the water (or lower the water container), thereby increasing the length (L) of the air column inside the tube. As you do this, listen carefully.

- Locate the First Loud Sound: At a specific length of the air column, you will hear a dramatic increase in the loudness of the sound. This is the fundamental resonant frequency (or first harmonic) of the air column. The air inside the tube is vibrating in sympathy (resonating) with the tuning fork.

- Measure the Length: Once you find this point of maximum resonance, hold the tube steady and carefully measure the length (L) of the air column from the water surface to the top of the tube.

Calculations:

For a tube closed at one end, the fundamental resonance occurs when the length of the air column is one-quarter of the wavelength (λ) of the sound wave.

The relationship is: L = λ/4

Therefore, you can calculate the wavelength: λ = 4L

Now, you can calculate the speed of sound (v) using the universal wave equation:

v = f λ

Where:

- v = speed of sound in air (what we are solving for)

- f = frequency of the tuning fork (known value)

- λ = wavelength (which you calculated as 4L)

Example:

If you used a 512 Hz tuning fork and found resonance at an air column length of 16.0 cm (0.160 m):

- Wavelength, λ = 4 × 0.160 m = 0.640 m

- Speed of sound, v = 512 Hz × 0.640 m = 327.68 m/s

The Key Approximation Made

The method makes one significant approximation:

The antinode of the sound wave is located exactly at the open end of the tube.

In reality, the point of maximum vibration (the displacement antinode) actually forms slightly above the physical end of the tube. This is due to the inertia of the air and is known as the “end effect” or “end correction.”

This means our measured length (L) is slightly shorter than the true effective resonant length of the air column. Consequently, our calculation of the wavelength (λ = 4L) is slightly too small, which leads to a calculated speed of sound that is slightly lower than the true value.

Question 36.

1. Complete the following sentences : Sound cannot travel through __________, but it requires a ___________.

2. Complete the following sentences : When sound travels in a medium, the particles of medium ___________ but the disturbance ___________.

3. Complete the following sentence : A longitudinal wave is composed of compression and ____________.

4. Complete the following sentence : A transverse wave is composed of a crest and ____________.

5. Complete the following sentences : Wave velocity = ________________ × wavelength.

Ans:

- Sound cannot travel through vacuum, but it requires a material medium.

- When sound travels in a medium, the particles of medium vibrate about their mean position but the disturbance travels (or propagates).

- A longitudinal wave is composed of compression and rarefaction.

- A transverse wave is composed of a crest and trough.

- Wave velocity = Frequency × wavelength.

Exercise 8 (A)

Question 1.

The correct statement is :

- Sound and light both require mediums for propagation.

- Sound can travel in vacuum, but light can not

- Sound needs medium, but light does not need medium for its propagation.

- Sound and light both can travel in vacuum.

Question 2.

The speed of sound in air at 0°C is nearly :

- 1450 m s-1

- 450 m s-1

- 5100 m s-1

- 330 m s-1

Question 3.

Sound in air propagates in form of

- Longitudinal wave

- Transverse wave

- Both longitudinal and transverse waves

- Neither longitudinal nor transverse wave.

Question 4.

The speed of light in air is :

- 3 x 108 m s-1

- 330 m s-1

- 5100 m s-1

- 3 x 1010 m s-1

Exercise 8 (A)

Question 1.

The heart of a man beats 75 times a minute. What is its (a) frequency and (b) time period?

Ans:

When analyzing any repeating event, such as a heartbeat, two fundamental concepts are its frequency and its time period. These two properties are inversely related to each other. Let’s break down the calculations based on the provided information.

(a) Determining the Frequency

Frequency simply tells us how often the event happens within a single second. The problem states that 75 beats occur over a duration of one minute.

Since the standard unit for frequency is Hertz (Hz), which is defined as cycles per second, our first step is to convert the given time into seconds.

- 1 minute is equivalent to 60 seconds.

The frequency is calculated by dividing the total number of beats by the total time in seconds:

Frequency (f) = Total Beats / Total Time

f = 75 beats / 60 seconds

Performing this division gives us:

f = 1.25 beats/second

This value is expressed in units of Hertz (Hz). Therefore, the frequency of the heartbeat is 1.25 Hz.

(b) Determining the Time Period

The time period is the duration it takes for a single, complete cycle of the event to occur. In this context, it is the time for one individual beat.

A key principle is that the time period is the mathematical reciprocal of the frequency. This means if you know how many times something happens in a second, you can find how long one occurrence takes by taking the reciprocal.

The formula is:

Time Period (T) = 1 / Frequency (f)

Using the frequency we calculated in part (a), which is 1.25 Hz:

T = 1 / 1.25

Calculating this gives:

T = 0.8 seconds

Thus, the time period for a single heartbeat is 0.8 seconds.

Summary of Results:

- (a) Frequency = 1.25 Hz

- (b) Time Period = 0.8 s

Question 2.

The time period of a simple pendulum is 2 s. Find its frequency.

Ans:

The heartbeat of a pendulum’s swing is described by two fundamental, interconnected concepts: its time period and its frequency.

The time period, denoted by T, is the duration the pendulum requires to make one complete journey back and forth. Imagine starting your stopwatch as the pendulum bob is at its highest left point, swinging to the right, and then returning to that original left position. The total time this takes is one time period. As stated in the problem, for this particular pendulum, that entire cycle consumes 2 seconds.

Frequency, symbolized by f, offers a different perspective. It doesn’t measure the duration of a single cycle but instead counts how many of these full oscillations occur within a single second. In essence, frequency is the oscillation’s rate or rhythm.

A direct and inverse mathematical relationship binds these two properties together. They are reciprocals of one another. The formula that expresses this is:

f = 1 / T

Since the time period (T) for our pendulum is a known 2 seconds, we determine the frequency by substituting this value into the equation:

f = 1 / 2 seconds

This calculation yields a result of 0.5 per second. The unit “per second” is universally known as the Hertz (Hz).

Therefore, a pendulum with a 2-second time period for one complete swing has a frequency of 0.5 Hz. This means it completes half of a full oscillation every single second.

Question 3.

The separation between two consecutive crests in a transverse wave is 100 m. If wave velocity is 20 m s-1, find the frequency of the wave.

Ans:

When analyzing a wave, two of its most fundamental properties are its wavelength and its speed. The wavelength is the distance over which the wave’s shape repeats, which, for a simple wave on water, is the gap from one crest to the next. In this scenario, that distance is provided as 100 meters.

The rate at which this wave pattern travels across the water is its velocity, given as 20 meters per second.

These two properties are mathematically linked by a third key property: frequency. Frequency measures how often a complete wave cycle passes a fixed point every second. The relationship that binds these three quantities together is a cornerstone of wave physics:

Wave Velocity = Frequency × Wavelength

To determine the frequency, this standard formula is rearranged. Dividing both sides of the equation by the wavelength isolates the frequency:

Frequency = Wave Velocity / Wavelength

Substituting the provided numerical values into this relationship gives:

Frequency = (20 m/s) / (100 m)

Completing this division, the unit of meters (m) cancels out, leaving units of per second (1/s), which is defined as Hertz (Hz).

Frequency = 0.2 Hz

Therefore, the wave completes 0.2 of a full cycle each second. In other words, one full wave crest passes a given point every 5 seconds.

Question 4.

A longitudinal wave travels at a speed of 0.3 m s-1 and the frequency of the wave is 20 Hz. Find the separation between two consecutive compressions.

Ans:

Problem Analysis:

We are given a sound wave, which is a longitudinal wave. Its speed is 0.3 meters per second, and it vibrates 20 times every second (its frequency is 20 Hz). We need to find the distance between two consecutive compressions.

Step-by-Step Solution:

Step 1: Understanding the Physical Meaning

The pattern of the wave—compression, followed by rarefaction (where particles are spread out), followed by the next compression—repeats over and over. The physical length of one of these repeating patterns is what we call the wavelength.

Therefore, the distance between two consecutive compressions is exactly one wavelength.

Step 2: Recalling the Fundamental Wave Relationship

There is a fundamental formula that connects the speed of a wave (v), its frequency (f), and its wavelength (λ). This formula is:

Wave Speed = Frequency × Wavelength

or

v = f × λ

This makes intuitive sense: how far the wave travels in one second (speed) is equal to how many wave cycles fit in that second (frequency) multiplied by the length of each cycle (wavelength).

Step 3: Performing the Calculation

We know the values for speed (v) and frequency (f), and we need to find the wavelength (λ).

λ = v / f

Plugging in the given values:

- Wave Speed (v) = 0.3 m/s

- Frequency (f) = 20 Hz (which means 20 cycles per second)

λ = (0.3 m/s) / (20 cycles/s)

When we perform the division, the units of “per second” (s⁻¹) cancel out, leaving us with an answer in meters.

λ = 0.015 meters

Step 4: Stating the Final Answer

Since the separation between consecutive compressions is one wavelength, our calculation directly gives the answer.

The separation between two consecutive compressions is 0.015 meters.

Question 5.

A source of wave produces 40 crests and 40 troughs in 0.4 s. What is the frequency of the wave?

Ans:

To determine the frequency of a wave, we need to find how many complete cycles occur each second. A single wave cycle consists of one crest followed by one trough.

Step 1: Determine the Total Number of Cycles

The source generates 40 crests and 40 troughs. Since every crest is paired with a trough to form one full cycle, the total number of complete wave cycles produced is 40.

Step 2: Identify the Total Time

The entire sequence of 40 cycles is created over a time span of 0.4 seconds.

Step 3: Apply the Frequency Formula

Frequency is defined as the number of cycles that happen per second. The formula is:

Frequency (f) = (Number of complete cycles) / (Total time)

Step 4: Perform the Calculation

Substituting the known values into the formula:

f = 40 cycles / 0.4 seconds

f = 100 cycles per second

Final Answer:

The frequency of the wave is 100 Hz.

Question 6.

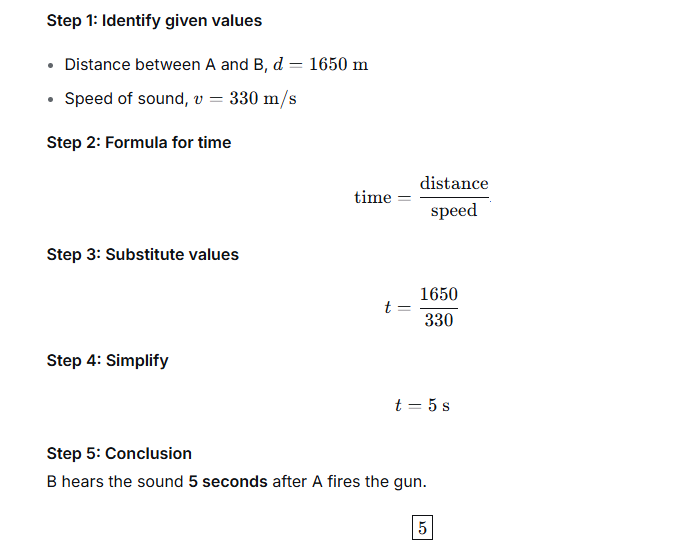

An observer A fires a gun and another observer B at a distance 1650 m away from A hears its sound. If the speed of sound is 330 m s-1, find the time when B will hear the sound after firing by A.

Ans:

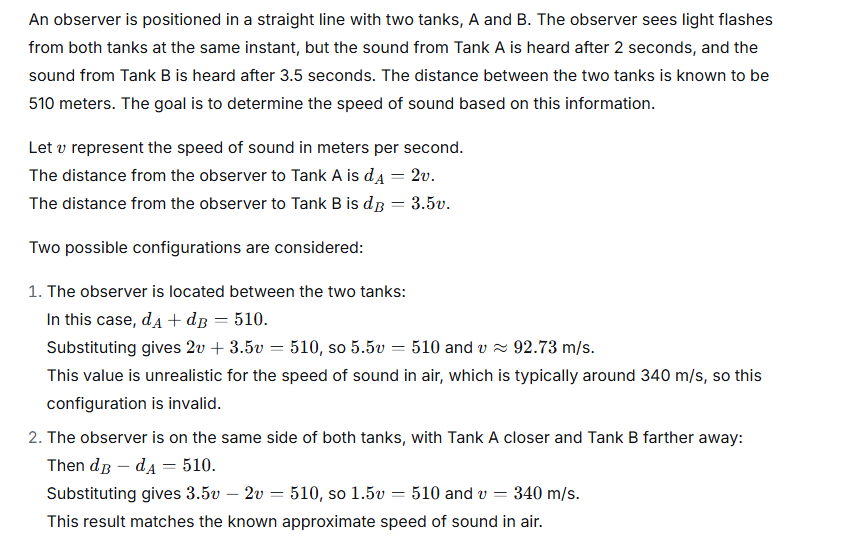

Question 7.

The time interval between a lightning flash and the first sound of thunder was found to be 5 s. If the speed of sound in air is 330 m s-1, find the distance of flash from the observer.

Ans:

Calculating the Distance to a Lightning Strike

Have you ever noticed that during a thunderstorm, you see the lightning flash before you hear the rumble of thunder? This happens because light travels to our eyes almost instantly, while sound moves through the air much more slowly. We can use this delay as a natural stopwatch to figure out how far away the storm is.

The Scenario:

You are observing a storm. You see a bright flash of lightning, and then, exactly five seconds later, you hear the clap of thunder. The speed at which sound travels through the air on this day is approximately 330 meters per second. Our goal is to determine how many meters away the lightning bolt struck.

The Reasoning Behind the Calculation:

- Light vs. Sound: The light from the lightning reaches your eyes in a fraction of a millisecond, which is negligible for this calculation. Therefore, the 5-second interval you measured is almost entirely the time it took for the sound of the thunder to travel through the air to your location.

- The Core Principle: The calculation relies on a fundamental relationship we use in everyday life: Distance is equal to speed multiplied by time. If you drive at 60 miles per hour for 2 hours, you’ve covered 120 miles. We are applying this same logic to the journey of sound.

Performing the Calculation:

We plug our known values directly into the formula:

- Distance = Speed of Sound × Time Interval

- Distance = 330 m/s × 5 s

When we multiply these numbers, the unit of seconds (s) cancels out, leaving us with an answer in meters (m).

330 × 5 = 1650

Question 8.

A boy fires a gun and another boy at a distance hears the sound of fire 2.5s after seeing the flash. If the speed of sound in air is 340 m/s, find distance between the boys.

Ans:

To find the distance between the two boys, we need to understand what happens when the gun is fired. The event creates two main signals: a bright flash of light and the loud sound of the gunshot.

Light travels to the second boy at an incredibly high speed, nearly 300 million meters per second. For any distance we would measure on Earth, the time it takes for the light to arrive is practically instantaneous. It is so fast that we can comfortably consider it to be zero seconds in this context.

The sound, however, moves much more slowly through the air. The problem states that the boy hears the sound 2.5 seconds after he sees the flash. This means the entire 2.5-second delay is the time it took for the sound to travel from the gun to his ears.