The study of Gas Laws begins by exploring the fundamental relationship between the volume, pressure, and temperature of a gas. It starts with Boyle’s Law, which states that for a fixed mass of gas at a constant temperature, the volume of the gas is inversely proportional to its pressure. This means if you squeeze a gas into a smaller space (increasing pressure), its volume decreases, provided the temperature doesn’t change. Following this is Charles’ Law, which explains how gases expand when heated. It establishes that for a fixed mass of gas at constant pressure, the volume is directly proportional to its absolute temperature (measured in Kelvin). So, as you heat a gas, its volume increases, and as you cool it, the volume contracts. These two laws lay the groundwork for understanding how gases behave under different physical conditions.

Building upon these individual laws, the chapter introduces the Combined Gas Law, which merges the principles of Boyle’s and Charles’ Laws. This powerful relationship shows how pressure, volume, and temperature are all interconnected for a given mass of any gas. It logically leads to the concept of an “ideal gas” and culminates in the Ideal Gas Equation (PV = nRT), a cornerstone formula in chemistry. This equation allows for calculations involving the number of moles of a gas. Finally, the chapter often covers Avogadro’s Law, which states that equal volumes of all gases, under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, contain an equal number of molecules. This principle is crucial as it provides the link between the volume of a gas and the number of particles it contains, solidifying our understanding of gaseous behavior at the molecular level.

Understanding these laws is not just theoretical; they have significant practical applications in daily life and technology. For instance, the principles explain why a balloon inflates when you blow air into it (increasing the number of moles and thus the volume), why a pressurized deodorant can warns against incineration (heating increases pressure, risking explosion as per Gay-Lussac’s Law), and how scuba divers must manage pressure changes to avoid conditions like “the bends.” In essence, the Gas Laws provide a predictable and mathematical framework for describing the behavior of gases, which is essential for fields ranging from meteorology and medicine to engineering.

Exercise 7 (A)

Question 1.

What do you understand about gas?

Ans:

Gas is one of the fundamental states of matter, distinct from solids and liquids. Its core trait is that its particles are spaced far apart and move freely and rapidly in all directions.

This results in a few key characteristics:

- No Fixed Shape or Volume: A gas will completely fill any sealed container it’s placed in, expanding to fit the entire space.

- Compressibility: Because of the empty space between particles, gases can be squeezed into a much smaller volume under pressure.

- Low Density: Gases are much lighter for their size compared to solids and liquids.

- Diffusion: Gases naturally mix and spread out through each other over time. You can smell perfume across a room because its gaseous particles diffuse into the air.

Question 2.

Give the assumptions of the kinetic molecular theory.

Ans:

- Negligible Volume: Gas particles are so small that their total volume is insignificant compared to the total volume of their container.

- Constant, Random Motion: Particles are in continuous, rapid, and straight-line motion.

- Elastic Collisions: Particles colliding with each other and the container walls do so without any loss of kinetic energy.

- No Forces: There are no attractive or repulsive forces between the particles.

- Temperature Dependence: The average kinetic energy of the particles is directly proportional to the absolute temperature of the gas.

Question 3.

During the practical session in the lab when hydrogen sulphide gas having offensive odour is prepared for some test, we can smell the gas even 50 metres away. Explain the phenomenon.

Ans:

The gas spreads so far due to the natural process of diffusion, where particles move from a high concentration (the lab) to a low concentration (the surrounding area).

This is particularly noticeable with hydrogen sulphide because our sense of smell is extremely sensitive to it. Our noses can detect incredibly tiny amounts of the gas in the air, meaning we can smell it long before it reaches a high or dangerous concentration 50 metres away.

Question 4.

What is diffusion? Give an example to illustrate it.

Ans:

Diffusion is the natural movement of particles—like atoms, molecules, or ions—from a region where they are more concentrated to a region where they are less concentrated. This happens because of random, constant motion, and it continues until the particles are evenly distributed in a space, reaching a state called equilibrium.

To picture this, imagine brewing a cup of coffee in a quiet kitchen. When the coffee first starts steaming, the rich aroma is strongest right near the cup. But within minutes, without any breeze or fan, the smell gently fills the entire room. That’s because the coffee vapor molecules drift away from the cup, where they’re densely packed, into the surrounding air, where they’re scarce. Over time, these molecules spread out evenly, so the scent becomes consistent throughout the kitchen. This everyday occurrence captures diffusion perfectly—no external force is needed, just the inherent motion of particles balancing themselves out.

Question 5.

How is molecular motion related to temperature?

Ans:

Temperature is fundamentally a measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles within a substance. This means that molecular motion and temperature are directly and inseparably linked. At a higher temperature, the molecules or atoms that make up a material possess greater kinetic energy, which causes them to move more vigorously. In a solid, this motion is primarily rapid vibration in a fixed position. In a liquid or gas, the increased energy translates into faster translational movement and more frequent, forceful collisions between particles. Essentially, the sensation of heat we perceive is a direct result of this intensified microscopic motion.

The type of motion varies with the state of matter, but the core principle remains. For instance, in a gas, temperature directly dictates the average speed of the freely moving molecules. In a liquid, molecules slide past each other with greater energy as temperature rises. Even in a rigid solid, where molecules are locked in place, a higher temperature means they vibrate more intensely within their lattice structure. This is why materials expand when heated—the increased motion pushes the particles slightly further apart on average.

Consequently, the concept of absolute zero (0 Kelvin or -273.15°C) is defined as the theoretical temperature at which all molecular motion would cease, meaning particles would have minimal possible kinetic energy. This underscores the direct proportionality: more motion equals higher temperature, less motion equals lower temperature. Therefore, we do not measure temperature as energy itself, but as a precise indicator of the average energy of this perpetual, chaotic dance of particles that constitutes all matter.

Question 6.

State (i) the three variables for gas laws and (ii) SI units of these variables.

Ans:

The three key variables involved in gas laws are pressure, volume, and temperature. These are essential in describing the state and behavior of gases in relationships like Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, and the Ideal Gas Law.

Regarding their SI units:

- Pressure is expressed in pascals (Pa), where 1 Pa equals 1 newton per square meter.

- Volume is measured in cubic meters (m³), which is the standard for space occupied.

- Temperature is given in kelvins (K), representing the absolute scale crucial for gas law calculations.

Question 7.

1. State Boyle’s Law.

2. Give its

(i) mathematical expression

(ii) graphical representation and

(iii) significance.

Ans:

Boyle’s Law describes a key relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas when its temperature is kept constant. According to this principle, for a fixed mass of a dry gas, increasing its pressure will cause its volume to decrease proportionally, and vice versa. Mathematically, this inverse relationship is expressed as PV = k, where ‘k’ is a constant. This means the product of the initial pressure and volume (P₁V₁) will always equal the product after a change (P₂V₂), allowing for practical calculations of how a gas will behave under compression or expansion.

This law can be visualized effectively through graphs. A plot of pressure against volume produces a distinctive curved line called a hyperbola or isotherm. A more straightforward linear graph is obtained by plotting pressure against the reciprocal of volume (1/V), which yields a straight line passing through the origin. These graphical representations confirm the predictable mathematical relationship between the two variables.

The real-world importance of Boyle’s Law is extensive, as it explains and predicts gas behavior in many everyday and scientific applications. It is the fundamental principle behind actions like drawing fluid into a syringe, the operation of a bicycle pump, and the compression of air in scuba tanks. Even the simple act of breathing relies on this concept, where changes in lung volume alter internal pressure to inhale and exhale air. By establishing this core behavior of gases, Boyle’s Law provided a critical foundation for the development of modern kinetic theory and our understanding of matter.

Question 8.

Explain Boyle’s Law on the basis of the kinetic theory of matter.

Ans:

Boyle’s Law captures an essential link between the pressure and volume of a gas when temperature is kept constant. Simply put, shrinking the volume of a gas causes its pressure to climb, while enlarging the volume leads to a drop in pressure. This inverse relationship means that, for a fixed amount of gas at a steady temperature, the product of pressure and volume always remains the same, expressed as

P×V=constant

P×V=constant.

The kinetic theory of gases offers a straightforward explanation for this pattern. Picture a gas as made up of countless tiny particles—atoms or molecules—that are in nonstop, chaotic motion. These particles zoom around, colliding with one another and with the walls of their container. The pressure exerted by the gas results from the endless barrage of these collisions against the walls, creating a steady push.

At a constant temperature, the average kinetic energy of the particles doesn’t change, so they maintain similar speeds. Each collision with the wall delivers about the same force. However, if the volume is reduced—say, by pushing in a piston—the same number of particles are crowded into a smaller area. With less space to move, particles travel shorter distances before hitting the walls, making collisions occur more often on any given section of the wall. Since pressure depends on how frequently these impacts happen, the pressure increases.

Conversely, when the volume is expanded, particles have more room to roam. They cover longer paths between collisions with the walls, so impacts become less frequent. With fewer collisions per unit area over time, the pressure decreases.

In summary, holding temperature steady means that volume changes directly affect how often gas particles strike the container walls. A smaller volume raises collision frequency and pressure, while a larger volume reduces both. This core idea from kinetic theory clarifies why pressure and volume are inversely related in Boyle’s Law.

Question 9.

The molecular theory states that the pressure exerted by a gas in a closed vessel results from the gas molecules striking against the walls of the vessel. How will the pressure change if The temperature is doubled keeping the volume constant

The volume is made half of its original value keeping the T constant

Ans:

Based on the molecular theory of gases, the pressure inside a closed vessel is caused by the countless collisions of fast-moving gas molecules against its walls. The magnitude of this pressure depends on two key factors: the force of each individual collision and the frequency of these collisions.

In the first scenario, where the temperature is doubled while the volume is held constant, the average kinetic energy of the gas molecules increases significantly. This means each molecule moves with a much higher speed. Furthermore, their increased speed also means they collide with the walls more often. The combined effect of these more forceful and more frequent collisions results in a direct increase in pressure. Specifically, since the average kinetic energy is proportional to the absolute temperature, doubling the absolute temperature while keeping the volume constant will cause the pressure to double as well.

For the second scenario, where the volume is halved while the temperature remains constant, the average speed and kinetic energy of the molecules stay the same. However, the same number of molecules are now confined to half the original space. This significantly increases the concentration of molecules within the vessel. With the molecules packed more densely, the distance they travel between collisions decreases drastically. This leads to a dramatic increase in the frequency at which they strike the walls, even though the force of each individual collision is unchanged. Therefore, the pressure increases due to the sheer number of collisions per second. According to Boyle’s Law, at a constant temperature, pressure is inversely proportional to volume. Halving the volume will exactly double the pressure exerted by the gas.

Question 10.

1. State Charles’s law

2. Give its (i) graphical representation,

(ii) mathematical expression

(iii) significance

Ans:

1. State Charles’s Law

Charles’s Law states that at constant pressure, the volume of a fixed mass of any gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature.

2. Give its:

(i) Graphical Representation:

Two standard graphs represent this law. The first is a Volume vs. Absolute Temperature (V-T) graph. For a fixed mass of gas at constant pressure, this graph is a straight line that slopes upwards and passes through the origin (0 K), confirming the direct proportionality. The second is a Volume vs. Temperature in Celsius (V-t) graph. Here, the plot is still a straight line, but when extrapolated backwards, it intersects the temperature axis at -273.15°C. This point signifies the theoretical temperature where the gas volume would become zero, establishing the concept of absolute zero.

(ii) Mathematical Expression:

The law can be expressed mathematically as:

V ∝ T (at constant pressure and mass)

Therefore, V/T = constant (k).

For a given gas undergoing a change, the relationship is: V₁ / T₁ = V₂ / T₂, where V is volume and T is absolute temperature (in Kelvin).

(iii) Significance:

The significance of Charles’s Law is foundational in understanding gas behavior. It quantitatively explains the expansion of gases upon heating and their contraction upon cooling at constant pressure. This principle is crucial in numerous real-world applications, such as the working of hot air balloons, where heating the air inside increases its volume and decreases its density, causing the balloon to rise. Furthermore, the law’s extrapolation to absolute zero (-273.15°C) provides a basis for the Kelvin thermodynamic temperature scale, which is essential for all scientific temperature measurements involving gases.

Question 11.

Explain Charles’s law on the basis of the kinetic theory of matter.

Ans:

Charles’s Law describes how gases tend to expand when heated, stating that at constant pressure, the volume of a fixed mass of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature. This behavior can be understood by examining the kinetic theory of matter, which provides a microscopic view of gas particles.

According to kinetic theory, a gas consists of numerous tiny particles—atoms or molecules—that are in continuous, random motion. These particles constantly collide with each other and with the walls of their container. The energy associated with this motion is kinetic energy, and the average kinetic energy of the particles is directly proportional to the absolute temperature of the gas. As temperature rises, particles move faster, and their average kinetic energy increases.

Pressure in a gas arises from the collisions of these particles with the container walls. Each collision exerts a force, and the collective force per unit area defines the pressure. When the temperature of a gas increases while pressure is held constant, the particles gain speed and collide with the walls more frequently and with greater impact. If the volume remained unchanged, this would lead to an increase in pressure. However, to maintain constant pressure—often by allowing a movable piston to adjust—the volume must expand.

This reduces the density of particles and spreads their collisions over a larger surface area. Consequently, the number of collisions per unit area decreases, balancing the heightened force from each collision due to higher temperature. This adjustment ensures that the force per unit area (pressure) remains steady.

In summary, from the kinetic theory perspective, Charles’s Law reflects the dynamic response of gas particles to temperature changes. Higher temperature boosts particle motion, necessitating a volume increase to dilute collision frequency and maintain constant pressure. Conversely, lower temperature slows particles down, requiring a volume decrease to concentrate collisions and preserve pressure. Thus, the direct proportionality between volume and absolute temperature emerges from the fundamental behavior of gas particles in motion.

Question 12.

Define absolute zero and absolute scale of temperature. Write about the relationship between °C and K.

Ans:

Absolute zero is the theoretical temperature at which the particles of matter (atoms and molecules) possess the minimum possible kinetic energy, meaning they cease all translational motion. While it can be approached very closely in laboratory conditions, it is impossible to reach this state entirely, as doing so would violate the principles of quantum mechanics.

The absolute scale of temperature, also known as the Kelvin scale, is a thermodynamic temperature scale that uses absolute zero as its null point (0 K). Unlike the Celsius or Fahrenheit scales, it does not use degrees and has no negative values, as it is based on an absolute physical limit. This makes it the fundamental scale for scientific work, particularly in physics and chemistry, because many physical laws and equations, such as those governing gas behavior (Charles’s Law), have their simplest and most direct form when temperature is expressed in Kelvin.

The relationship between the Celsius (°C) and Kelvin (K) scales is direct and linear, as they share the same size for a unit increment. The only difference is their starting points. The Kelvin scale is essentially the Celsius scale shifted so that its zero point aligns with absolute zero. Therefore, 0 K is equal to -273.15°C. The conversion between the two is straightforward: Kelvin temperature = Celsius temperature + 273.15. Conversely, Celsius temperature = Kelvin temperature – 273.15. Crucially, a change of 1°C is exactly equal to a change of 1 K, meaning the scales measure temperature intervals identically.

Question 13.

1. What is the need for the Kelvin scale of temperature?

2. What is the boiling point of water on the Kelvin scale? Convert it into a centigrade scale.

Ans:

1. Need for the Kelvin Scale of Temperature

The Kelvin scale is primarily used in scientific research and applications because it is an absolute temperature scale. Its zero point, 0 K (known as absolute zero), corresponds to the theoretical state where all molecular motion ceases, meaning there is no thermal energy. This absolute reference eliminates negative temperatures, simplifying many physical and chemical equations. For instance, in thermodynamics, gas laws, and energy calculations, relationships like the Ideal Gas Law (PV = nRT) require temperature in Kelvin to maintain direct proportionality between temperature and energy. Using Celsius or Fahrenheit, which have arbitrary zero points, would introduce complexities in such equations. Thus, Kelvin provides a consistent and universally applicable measure for scientific work, ensuring accuracy in studies involving heat, entropy, and kinetic theory.

2. Boiling Point of Water on the Kelvin Scale and Conversion

To convert this to the Celsius (centigrade) scale, the formula is:

°C = K – 273.15

Applying this: 373.15 K – 273.15 = 100 °C.

Therefore, the boiling point of water is 100 °C on the Celsius scale.

Question 14.

1. Define S.T.P.

2. Why is it necessary to compare gases at S.T.P?

Ans:

1. Definition of S.T.P.

S.T.P. stands for Standard Temperature and Pressure. It is a fixed reference point used for measuring and comparing the properties of gases. Specifically, it is defined as a temperature of 0° Celsius (273 Kelvin) and a pressure of 760 millimetres of mercury (which is equivalent to one standard atmosphere, or 101.325 kilopascals). By establishing these exact conditions, scientists and chemists have a common baseline for their work.

2. Necessity of Comparing Gases at S.T.P.

It is necessary to compare gases at S.T.P. because the volume of a gas is highly sensitive to changes in both temperature and pressure. A given amount of gas will expand when heated or when the surrounding pressure decreases, and it will contract when cooled or when the pressure increases. If gases were measured under different conditions of temperature and pressure, their volumes would be entirely different, making any direct comparison or calculation meaningless. Using S.T.P. eliminates this variability.

By converting all gas volumes to their equivalent at the standard conditions of 0°C and 760 mm Hg, we create a “level playing field.” This allows for accurate comparisons, consistent chemical calculations, and the application of fundamental laws like Avogadro’s Law, which states that at S.T.P., one mole of any gas occupies the same fixed volume (approximately 22.4 litres). In essence, S.T.P. provides the universal standard needed for clarity, consistency, and accuracy in the study of gaseous behaviour.

Question 15.

1. Write the value of: the standard temperature in:

(i) °C

(ii) K

2. Write the values of: standard pressure in:

(i) atm

(ii) mm Hg

(iii) cm Hg

(iv) torr

Ans:

- Standard Temperature

(i) 0 °C

(ii) 273.15 K - Standard Pressure

(i) 1 atm

(ii) 760 mm Hg

(iii) 76 cm Hg

(iv) 760 torr

Question 16.

1. What is the relationship between the Celsius and Kelvin scales of temperature?

2. Convert (i) 273°C to Kelvin and (ii) 293 K to °C.

Ans:

The Celsius and Kelvin scales are directly related, as they both measure temperature but use different starting points. The key difference is that 0 K, known as absolute zero, represents the point where all molecular motion theoretically ceases. In contrast, 0°C is defined as the freezing point of water. The size of one unit (degree) is identical on both scales. To convert between them, you use the formula: Kelvin = Celsius + 273. This means 0°C is equal to 273 K, showing that the Kelvin scale is essentially the Celsius scale shifted by 273 units.

Using this relationship, the conversions are straightforward. For (i) 273°C to Kelvin, you simply add 273. Therefore, 273°C + 273 = 546 K. For (ii) 293 K to °C, you reverse the operation by subtracting 273 from the Kelvin value. So, 293 K – 273 = 20°C. These calculations highlight the practical application of the simple additive relationship between the two temperature scales.

Question 17.

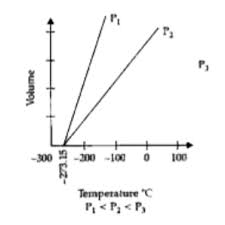

1. State the law which is represented by the following graph:

2. State the law which is represented by the following graph:

Ans:

1. The graph of Volume versus Temperature (°C) with multiple lines at constant pressures P₁, P₂, P₃ (where P₁ < P₂ < P₃) represents Charles’s Law.

2. The graph of Pressure versus 1/Volume with multiple lines at constant temperatures T₁, T₂, T₃ (where T₃ > T₂ > T₁) represents Boyle’s Law.

It states that at constant temperature, the pressure of a fixed mass of gas is inversely proportional to its volume.

Question 18.

1. Give reason for the following: All temperatures in the absolute (Kelvin) scale is in positive figures.

2. Give reason for the following: Gases have a lower density compared to solids or liquids.

3. Give reason for the following: Gases exert pressure in all directions.

4. Give reasons for the following: It is necessary to specify the pressure and temperature of gas while stating its volume.

5. Give reasons for the following: Mountaineers carry oxygen cylinders with them.

6. Give reasons for the following: Gas fills the vessel completely in which it is kept.

Ans:

1. The absolute (Kelvin) scale starts at absolute zero, which is the theoretical temperature where all molecular motion ceases. As it is the lowest possible temperature, there is no value below it; hence, all measurements on this scale are positive figures, representing energy content above this absolute minimum.

2. Gases have a much lower density compared to solids or liquids because the particles in a gas are spaced very far apart. In solids and liquids, particles are tightly packed, resulting in more mass per unit volume, whereas in gases, the large empty spaces between moving particles lead to a very low mass occupied in a given space.

3. Gases exert pressure in all directions because their particles are in constant, rapid, and random motion. These freely moving particles collide continuously and equally with all walls of their container, thereby applying force per unit area, or pressure, uniformly on every surface they contact.

4. It is necessary to specify the pressure and temperature while stating the volume of a gas because gases are highly compressible and expand on heating. The volume of a given mass of gas changes significantly with variations in pressure (Boyle’s Law) and temperature (Charles’s Law); therefore, without stating these conditions, the volume figure is meaningless.

5. Mountaineers carry oxygen cylinders because the concentration (partial pressure) of oxygen in the air decreases at high altitudes. As they ascend, the thin atmosphere cannot supply enough oxygen per breath for normal respiration, leading to altitude sickness. The cylinders provide supplemental oxygen to meet their body’s metabolic needs.

6. A gas fills the vessel completely in which it is kept due to the high kinetic energy of its particles and negligible forces of attraction between them. The particles move rapidly in all available space, diffusing and spreading out uniformly until they hit the walls of the container, thus occupying its entire volume.

Question 19.

How did Charles’s law lead to the concept of an absolute scale of temperature?

Ans:

Charles’s law emerged from experimental observations in the 18th and 19th centuries, which showed that for a fixed amount of gas under constant pressure, its volume expanded predictably as the temperature increased. When researchers plotted volume against temperature using common scales like Celsius, they noticed a straight-line relationship. However, this line did not originate at zero volume when temperature was zero degrees Celsius; instead, it intersected the temperature axis at approximately -273.15°C. This indicated that if the gas continued to contract linearly, its volume would theoretically reach zero at that point.

This extrapolation was pivotal because it suggested a natural limit to how cold matter could become—a temperature where molecular motion would essentially cease. Since negative volumes are physically meaningless, this implied an absolute minimum temperature, later termed absolute zero. Consequently, scientists recognized the need for a temperature scale that aligned with this fundamental baseline. By shifting the zero point to absolute zero, they created the absolute temperature scale, now known as the Kelvin scale. In this system, temperature increments match those of Celsius, but zero Kelvin corresponds to -273.15°C, ensuring that Charles’s law simplifies to a direct proportionality between volume and absolute temperature. Thus, Charles’s law provided the empirical foundation for conceiving an absolute scale, where temperature measurements are rooted in a universal physical reality rather than arbitrary references.

Question 20.

What is meant by aqueous tension? How is the pressure exerted by a gas corrected to account for aqueous tension?

Ans:

Aqueous Tension

In laboratory settings, gases are often collected over water through the method of water displacement. In such a situation, the gas that is collected is never pure; it becomes mixed with water vapour. This occurs because water molecules at the surface continuously evaporate, creating a pressure inside the container due to this vapour. Aqueous tension is defined as the pressure exerted by the saturated water vapour present in the space above the liquid water at a specific temperature. It is essentially the saturated vapour pressure of water at that temperature, and its value increases as the temperature rises.

Correcting Gas Pressure for Aqueous Tension

The total pressure measured in a gas jar collected over water is the sum of the pressure exerted by the dry gas and the pressure exerted by the water vapour (aqueous tension). Therefore, to obtain the true pressure of the dry gas alone—which is required for accurate calculations using the gas laws—the aqueous tension must be subtracted.

The correction is applied using a simple formula:

Pressure of dry gas = Total pressure of the moist gas – Aqueous tension at the given temperature

For example, if the total atmospheric pressure is recorded as 750 mmHg and the aqueous tension at the experiment’s temperature is 20 mmHg, then the actual pressure attributable to the dry, collected gas is 750 – 20 = 730 mmHg. This corrected value is used in all subsequent calculations to determine the gas’s volume under standard conditions or its number of moles.

Question 21.

1. State the following: The volume of a gas at 0 Kelvin

2. State the following: The absolute temperature of a gas at 7°C

3. State the following: Gas equation

4. State the following: Ice point in absolute temperature

5. State the following: STP conditions

Ans:

1. The volume of a gas at 0 Kelvin

According to Charles’s Law, the volume of a fixed mass of a gas becomes zero at 0 Kelvin (absolute zero). This is a theoretical extrapolation as all real gases would liquefy and solidify well before reaching this temperature, but the ideal gas model predicts zero volume at this point.

2. The absolute temperature of a gas at 7°C

The absolute temperature, measured on the Kelvin scale, is obtained by adding 273 to the Celsius temperature. Therefore, for a gas at 7°C, the absolute temperature is 7 + 273 = 280 Kelvin (280 K).

3. Gas equation

The general gas equation, also known as the ideal gas equation, combines Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, and Avogadro’s Law. It is stated as PV = nRT, where P is pressure, V is volume, n is the number of moles, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.

4. Ice point in absolute temperature

The ice point, which is the freezing point of pure water under standard atmospheric pressure, is 0°C on the Celsius scale. On the absolute (Kelvin) temperature scale, this corresponds to 273 K.

5. STP conditions

STP stands for Standard Temperature and Pressure. The standard conditions are defined as a temperature of 0°C (273 K) and a pressure of 760 millimetres of mercury (mmHg) or 1 atmosphere (atm). Under these conditions, one mole of any ideal gas occupies a volume of 22.4 litres (or 22.4 dm³).

Question 22.

1. Choose the correct answer: The graph of PV vs P for gas is

- Parabolic

- Hyperbolic

- A straight line parallel to the X-axis

- A straight line passing through the origin

2. Choose the correct answer: The absolute temperature value that corresponds to 27°C is

- 200 K

- 300 K

- 400 K

- 246 K

3. Choose the correct answer: The volume-temperature relationship is given by

- Boyle

- Gay-Lussac

- Dalton

- Charles

4. Choose the correct answer:If the pressure is doubled for a fixed mass of a gas, its volume will become

- 4 times

- ½ times

- 2 times

- No change

Question 23.

Match the following:

| Column A | Column B | |

| (a) | cm3 | (i) Pressure |

| (b) | Kelvin | (ii) Temperature |

| (c) | Torr | (iii) Volume |

| (d) | Boyle’s law | (iv) V/ T = V1/T1 |

| (a) | Charles’s law | (v) PV / T = P1V1 / T1 |

| (vi) PV = P1V1 |

Ans:

| Column A | Match | Column B |

| (a) cm3 | (iii) | Volume |

| (b) Kelvin | (ii) | Temperature |

| (c) Torr | (i) | Pressure |

| (d) Boyle’s law | (vi) | PV=P1V1 (Constant Temperature) |

| (e) Charles’s law | (iv) | V/T=V1/T1 (Constant Pressure) |

Question 24.

1. Correct the following statement: The volume of a gas is inversely proportional to its pressure at a constant temperature.

2. Correct the following statement: The volume of a fixed mass of a gas is directly proportional to its temperature, pressure remaining constant.

3. Correct the following statement: 0°C is equal to zero Kelvin.

4. Correct the following statement: The standard temperature is 25°C.

5. Correct the following statement: The boiling point of water is 273 K.

Ans:

- For a specific quantity of gas, the volume increases as pressure decreases, and vice versa, but only when the temperature is held steady. This principle is known as Boyle’s law.

- When the pressure is constant, the volume of a fixed amount of gas grows as its absolute temperature (measured on the Kelvin scale) increases. This relationship is described by Charles’s law.

- Zero degrees Celsius is equivalent to 273.15 Kelvin, not zero Kelvin. Zero Kelvin represents absolute zero, which is -273.15°C.

- In gas law calculations, standard temperature is typically 0°C (273.15 K), not 25°C. Standard conditions may vary, but for gases, 0°C is commonly used.

- Under standard atmospheric pressure, water boils at 373.15 Kelvin. The value 273 K corresponds to the freezing point of water, not its boiling point.

Question 25.

1. Fill in the blanks: The average kinetic energy of the molecules of a gas is proportional to the ………….

2. Fill in the blanks: The temperature on the Kelvin scale at which molecular motion completely ceases is called……………

3. Fill in the blanks: If the temperature is reduced to half, ………….. would also reduce to half.

4. Fill in the blanks: The melting point of ice is …………. Kelvin.

Ans:

- The average kinetic energy of the molecules of a gas is proportional to the absolute temperature (or Kelvin temperature).

- The temperature on the Kelvin scale at which molecular motion completely ceases is called absolute zero (K).

- If the temperature is reduced to half, pressure or volume (depending on the fixed variable) would also reduce to half.

- The melting point of ice is 273.15 Kelvin.

Exercise 7 (B)

Question 1.

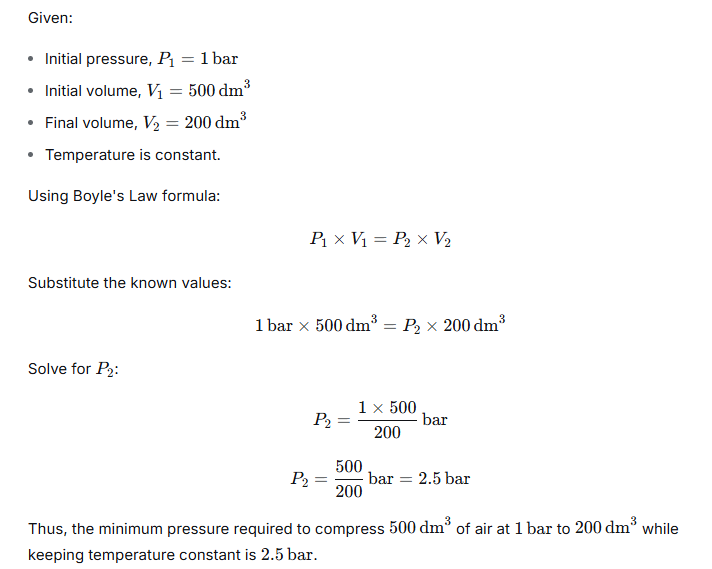

What will be the minimum pressure required to compress 500 dm3 of air at 1 bar to 200 dm3 temperature remaining constant?

Ans:

Question 2.

2 liters of gas is enclosed in a vessel at a pressure of 760 mmHg. If the temperature remains constant, calculate pressure when volume changes to 4 dm3.

Ans:

Based on Boyle’s Law, which states that for a fixed mass of gas at constant temperature, pressure is inversely proportional to volume, we can solve this problem.

We are given:

Initial Pressure, P1 = 760 mmHg

Initial Volume, V1 = 2 liters

Final Volume, V2 = 4 dm³

Since 1 dm³ is equal to 1 liter, V2 = 4 liters. The temperature remains constant, so Boyle’s Law applies: P1V1 = P2V2.

Substituting the known values:

(760 mmHg) * (2 L) = P2 * (4 L)

Solving for P2:

P2 = (760 * 2) / 4 = 1520 / 4 = 380 mmHg

Therefore, when the volume increases to 4 dm³ at constant temperature, the new pressure inside the vessel will be 380 mmHg.

Question 3.

At constant temperature, the effect of change of pressure on the volume of a gas was as given below:

| Pressure in atmosphere | Volume in liters |

| 0.20 | 112 |

| 0.25 | 89.2 |

| 0.40 | 56.25 |

| 0.60 | 37.40 |

| 0.80 | 28.10 |

| 1.00 | 22.4 |

(a) Plot the following graphs

P vs V

P vs 1/V

PV vs P

Interpret each graph in terms of the law.

(b) Assuming that the pressure values given above are correct, find the correct measurement of the volume.

Ans:

Part (a): Analysis of Graphs

Data Summary:

| Pressure (P) atm | Volume (V) L | 1/V (L⁻¹) | PV (atm·L) |

| 0.20 | 112.0 | 0.00893 | 22.40 |

| 0.25 | 89.2 | 0.01121 | 22.30 |

| 0.40 | 56.25 | 0.01778 | 22.50 |

| 0.60 | 37.40 | 0.02674 | 22.44 |

| 0.80 | 28.10 | 0.03559 | 22.48 |

| 1.00 | 22.4 | 0.04464 | 22.40 |

1. Plot of Pressure versus Volume

When pressure is plotted on the vertical axis and volume on the horizontal axis, the resulting curve is hyperbolic. It begins at a high pressure for the smallest volume and decreases steeply, gradually flattening as volume increases. This distinctive shape illustrates the core principle that, for a fixed amount of gas at a steady temperature, pressure and volume change in opposite directions. The curve’s approach to both axes without intersecting them visually confirms their inverse relationship.

2. Plot of Pressure versus Inverse Volume

Graphing pressure against the reciprocal of volume (1/V) produces a straight-line trend. This line, when extended, passes near or through the point of origin (0,0). The linearity of this graph is key: it transforms the inverse relationship into a direct one. The underlying equation can be expressed as P = k × (1/V), matching the standard form of a line (y = mx) with a slope equal to the constant *k* and no intercept. This straight-line fit strongly supports the theoretical prediction of Boyle’s Law.

3. Plot of the Product PV versus Pressure

A graph of the product (Pressure × Volume) against pressure itself yields points clustered around a nearly horizontal line. According to theory, this product should remain perfectly constant. The observed slight variations above and below a central value represent minor measurement inconsistencies, likely in reading the volume. The overall horizontal pattern, however, validates the expected constant behavior of the PV product under the experimental conditions.

Part (b): Determining the Most Accurate Volume Measurements

Boyle’s Law states that for an ideal gas at constant temperature, the product of pressure and volume (PV) is a fixed number. The calculated products from the data set are:

- 0.20 atm × 112.0 L = 22.40

- 0.25 atm × 89.2 L = 22.30

- 0.40 atm × 56.25 L = 22.50

- 0.60 atm × 37.40 L = 22.44

- 0.80 atm × 28.10 L = 22.48

- 1.00 atm × 22.4 L = 22.40

The average of these six products is calculated as:

(22.40 + 22.30 + 22.50 + 22.44 + 22.48 + 22.40) / 6 = 134.52 / 6 = 22.42 atm·L.

This average value (22.42) is taken as the best experimental estimate of the true constant *k*. Corrected volumes that would yield this exact product for each pressure can be found using the rearranged law: V_corrected = k / P.

| Pressure (P) atm | Original Volume (V) L | Corrected Volume (V_c) L |

| 0.20 | 112.0 | 22.42 / 0.20 = 112.1 |

| 0.25 | 89.2 | 22.42 / 0.25 = 89.68 |

| 0.40 | 56.25 | 22.42 / 0.40 = 56.05 |

| 0.60 | 37.40 | 22.42 / 0.60 = 37.37 |

| 0.80 | 28.10 | 22.42 / 0.80 = 28.03 |

| 1.00 | 22.4 | 22.42 / 1.00 = 22.42 |

Interpretation: The corrected volumes represent the ideal measurements that would make every data point perfectly consistent with Boyle’s Law, giving a constant product of 22.42 atm·L. The small discrepancies between the original and corrected values highlight the inherent, minor errors present in the initial experimental procedure, most probably in determining the volume.

Question 4.

800 cm3 of gas is collected at 654 mm pressure. At what pressure would the volume of the gas reduce by 40% of its original volume, the temperature remaining constant?

Ans:

To determine the new pressure of the gas, we first find its reduced volume. The original volume is 800 cm³. A 40% reduction means the volume decreases by 320 cm³ (calculated as 0.40 multiplied by 800). The resulting volume, V₂, is therefore 800 minus 320, equaling 480 cm³.

The relationship between the initial and final states of the gas is governed by Boyle’s Law. This principle tells us that for a fixed mass of gas at constant temperature, the product of its pressure and volume remains constant. In practical terms, this means the initial pressure multiplied by the initial volume (P₁V₁) equals the final pressure multiplied by the final volume (P₂V₂). With starting values of P₁ = 654 mm Hg and V₁ = 800 cm³, we can set up the equation 654 * 800 = P₂ * 480.

Solving for the unknown final pressure, P₂, involves dividing the initial product by the new volume. The calculation 654 multiplied by 800 gives 523,200. Dividing this result by 480 yields a final pressure of 1,090 mm Hg. Thus, compressing the gas to 480 cm³ increases its pressure to this value.

Question 5.

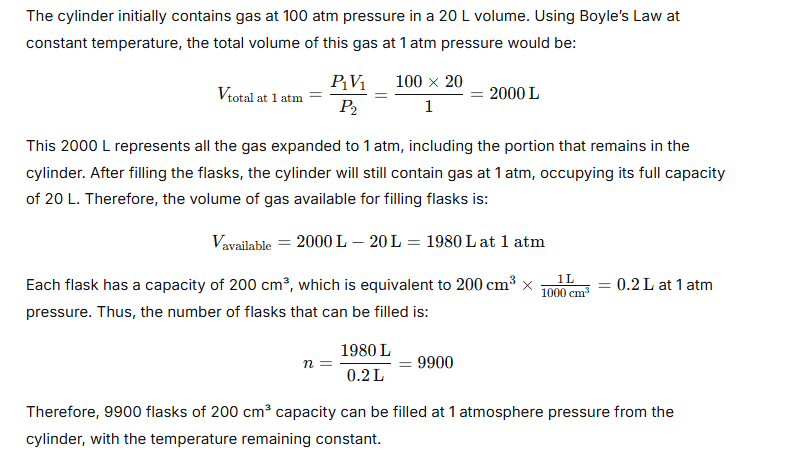

A cylinder of 20 liters capacity contains gas at 100 atmospheric pressure. How many flasks of 200 cm3capacity can be filled from it at 1-atmosphere pressure, temperature remaining constant?

Ans:

Question 6.

A steel cylinder of internal volume 20 litres is filled with hydrogen at 29 atmospheric pressure. If hydrogen is used to fill a balloon at 1.25 atmospheric pressure at the same temperature, what volume will the gas occupy?

Ans:

Let’s consider a steel cylinder holding 20 litres of hydrogen gas under a high pressure of 29 atmospheres. If this gas is moved into a balloon where the pressure is only 1.25 atmospheres, and the temperature doesn’t change, the gas will spread out and take up much more space. This happens because, for a fixed amount of gas at constant temperature, the squeezing force (pressure) and the amount of room it takes up (volume) are inversely related—a principle known as Boyle’s Law.

We can use the formula from this law, which states that the starting pressure multiplied by the starting volume equals the ending pressure multiplied by the ending volume. Plugging in our numbers: 29 atmospheres times 20 litres equals 1.25 atmospheres times the unknown final volume. Doing the multiplication gives 580 on one side, so to find the final volume, we divide 580 by 1.25. This calculation gives us a result of 464 litres.

Therefore, when the hydrogen gas is allowed to expand into the balloon at the much lower pressure, its volume increases dramatically to 464 litres. This clearly shows how a gas will fill a much larger area when the confining pressure is reduced.

Question 7.

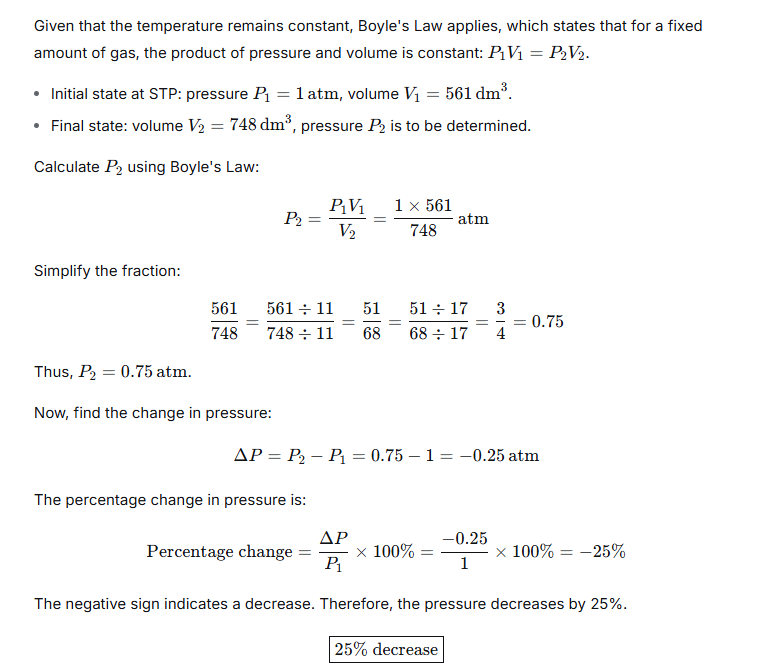

561 dm3 of a gas at STP is filled in a 748 dm3 container. If the temperature is constant, calculate the percentage change in pressure required.

Ans:

Question 8.

88 cm3 of nitrogen is at a pressure of 770 mm mercury. If the pressure is raised to 880 mmHg, find by how much the volume will diminish, the temperature remaining constant.

Ans:

This problem is solved using Boyle’s Law, which states that for a fixed mass of gas at constant temperature, the pressure and volume are inversely proportional. This means the product of the initial pressure and volume will equal the product of the final pressure and volume.

We start with the initial values: Volume 1 (V₁) is 88 cm³, and Pressure 1 (P₁) is 770 mmHg. The new pressure, P₂, is increased to 880 mmHg. The temperature remains constant, so we apply the formula P₁V₁ = P₂V₂. Substituting the known values gives us 770 mmHg * 88 cm³ = 880 mmHg * V₂. To find the new volume, V₂, we calculate (770 * 88) / 880. This simplifies to 77 cm³, as 880 divided by 11 is 80, and 770 divided by 10 is 77 in the intermediate steps.

Therefore, the new volume is 77 cm³. The question asks for how much the volume will diminish. The original volume was 88 cm³, and the new volume is 77 cm³. The decrease is found by simple subtraction: 88 cm³ – 77 cm³ = 11 cm³. So, when the pressure is increased from 770 mmHg to 880 mmHg, the volume of the nitrogen gas will diminish by 11 cubic centimeters.

Question 9.

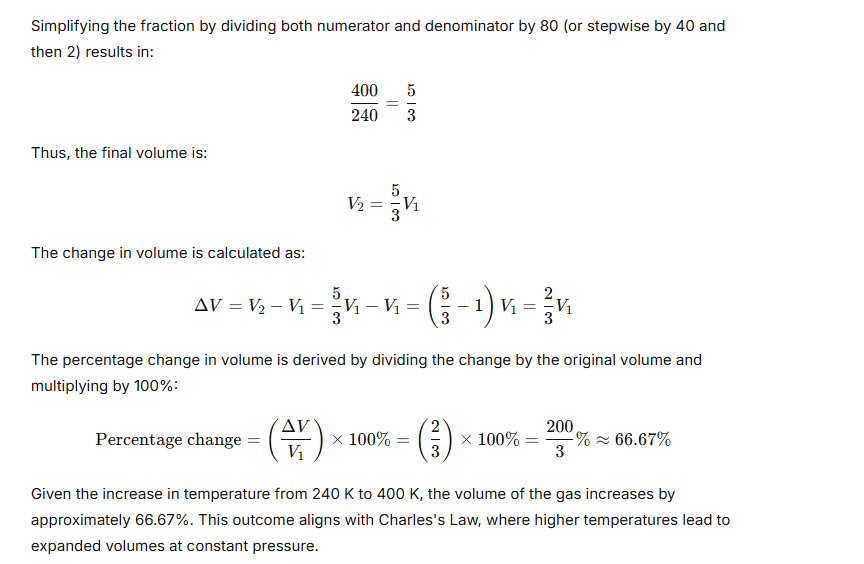

A gas at 240 K is heated to 127°C. Find the percentage change in the volume of the gas (pressure remaining constant).

Ans:

Question 10.

A certain amount of a gas occupies a volume of 0.4 litre at 17°C. To what temperature should it be heated so that its volume gets (a) doubled, (b) reduced to half, pressure remaining constant?

Ans:

Question 11.

A given mass of a gas occupied 143 cm3 at 27° C and 700 mm Hg pressure. What will be its volume at 300 K and 280 mm Hg pressure?

Ans:

We can solve this using the combined gas law, which relates the pressure, volume, and temperature of a gas when the amount is constant. The formula is expressed as (P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂. It’s crucial to ensure all temperatures are in the Kelvin scale. First, we convert the initial temperature: 27°C is equal to 27 + 273 = 300 K. Interestingly, the final temperature given is also 300 K. This means the temperature is constant throughout the change.

Since T₁ equals T₂ (both 300 K), they cancel each other out in the combined gas law. The problem therefore simplifies to Boyle’s Law: P₁V₁ = P₂V₂. Now we can plug in the known values: P₁ = 700 mm Hg, V₁ = 143 cm³, and P₂ = 280 mm Hg. Solving for the final volume, V₂ = (P₁V₁) / P₂.

Performing the calculation: V₂ = (700 mm Hg * 143 cm³) / 280 mm Hg. This works out to 100,100 / 280, which gives a final volume of 357.5 cm³. So, under the new conditions of 280 mm Hg pressure and 300 K, the gas will occupy 357.5 cubic centimeters.

Question 12.

A gas occupies 500 cm3 at a normal temperature. At what temperature will the volume of the gas be reduced by 20% of its original volume, the pressure is constant?

Ans:

Question 13.

Calculate the final volume of a gas ‘X’ if the original pressure of the gas at STP is doubled and its temperature is increased three times.

Ans:

Based on the principles of gas laws, we can solve this problem by applying the combined gas law, which states that for a fixed mass of gas, the ratio of its pressure-volume product to its absolute temperature remains constant.

Let’s denote the initial conditions at STP. We’ll assume the initial volume of gas ‘X’ is V₁. According to the problem, the final pressure (P₂) is doubled, so P₂ = 2 atm, and the final temperature (T₂) is increased three times, so T₂ = 3 × 273 K = 819 K.

Applying the combined gas law formula: (P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂. Substituting the known values gives us (1 × V₁) / 273 = (2 × V₂) / 819. To solve for the final volume V₂, we cross-multiply: 819V₁ = 2 × 273 × V₂, which simplifies to 819V₁ = 546V₂. Dividing both sides by 546 results in V₂ = (819 / 546) V₁.

Simplifying the fraction 819/546 by dividing both numerator and denominator by 273 gives V₂ = (3 / 2) V₁. Therefore, the final volume of gas ‘X’ is 1.5 times its original volume. In essence, the tripling of the temperature increases the volume, while the doubling of the pressure decreases it; the net effect is a 50% increase from the starting volume.

Question 14.

A sample of carbon dioxide occupies 30 cm3 at 15°C and 740 mm pressure. Find its volume at STP.

Ans:

The volume of carbon dioxide at STP (0°C and 760 mm Hg) is approximately 27.7 cm³. This is calculated using the combined gas law, converting temperatures to Kelvin, and simplifying the resulting expression.

Question 15.

What temperature would be necessary to double the volume of a gas initially at s.t.p. if the pressure is decreased by 50%?

Ans:

To solve this, we use the combined gas law: P₁V₁/T₁ = P₂V₂/T₂. The gas starts at Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP), defined as a temperature (T₁) of 273 K and a pressure (P₁) of 1 atm. We are told the final volume (V₂) is double the initial volume (V₁), and the final pressure (P₂) is decreased by 50%, meaning it is 0.5 atm.

Assigning the values: Let V₁ = V. Therefore, V₂ = 2V. P₁ = 1 atm, P₂ = 0.5 atm, and T₁ = 273 K. Substituting into the gas law gives:

(1 atm * V) / 273 K = (0.5 atm * 2V) / T₂

Simplifying the right side: 0.5 atm * 2V = 1 atm * V. The equation becomes:

(1 * V) / 273 = (1 * V) / T₂

Since the term “1 * V” appears on both sides, it cancels out. This leaves the equation: 1 / 273 = 1 / T₂. Solving for T₂ gives T₂ = 273 K.

Therefore, the necessary final temperature is 273 K (which is 0°C). This result shows that if the pressure is halved, the volume will double at the original constant temperature, according to Boyle’s Law. No change in temperature is required.

Question 16.

At 0°C and 760 mmHg pressure, a gas occupies a volume of 100 cm3. The Kelvin temperature of the gas is increased by one-fifth and the pressure is increased one and a half times. Calculate the final volume of the gas.

Ans:

The initial conditions are a temperature of 0°C (which is 273 K), a pressure of 760 mmHg, and a volume of 100 cm³. The gas undergoes two changes: first, its Kelvin temperature is increased by one-fifth, and second, its pressure is increased one and a half times.

The new temperature becomes 273 K + (1/5 × 273 K) = 273 K + 54.6 K = 327.6 K. The new pressure becomes 760 mmHg × 1.5 = 1140 mmHg. To find the new volume, we apply the combined gas law: (P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂. Rearranging to solve for the final volume gives V₂ = (P₁V₁T₂) / (T₁P₂).

Substituting the known values: V₂ = (760 mmHg × 100 cm³ × 327.6 K) / (273 K × 1140 mmHg). Performing the calculation, the final volume of the gas is found to be 80 cm³.

Question 17.

It is found that on heating a gas its volume increases by 50% and its pressure decreases to 60% of its original value. If the original temperature was −15°C, find the temperature to which it was heated.

Ans:

The initial temperature is given as −15°C, which in the Kelvin scale is 273 + (−15) = 258 K.

Upon heating, the volume increases by 50%, making the new volume V₂ = V₁ + 0.5V₁ = 1.5V₁. Simultaneously, the pressure decreases to 60% of its original value, so the new pressure is P₂ = 0.6P₁. To find the final temperature (T₂), we apply the combined gas law, which states that for a fixed mass of gas, the ratio PV/T remains constant. Therefore, P₁V₁ / T₁ = P₂V₂ / T₂.

Substituting the known values gives: (P₁ * V₁) / 258 = (0.6P₁ * 1.5V₁) / T₂. The terms P₁ and V₁ cancel out from both sides. This simplifies to 1 / 258 = 0.9 / T₂. Solving for T₂, we find T₂ = 0.9 * 258 = 232.2 K.

To express this final temperature in degrees Celsius, we subtract 273 from the Kelvin value: 232.2 − 273 = −40.8°C. Thus, despite the process being initiated by heating, the significant drop in pressure alongside the volume expansion results in a net decrease in the gas’s temperature to approximately −41°C.

Question 18.

A certain mass of a gas occupies 2 litres at 27°C and 100 Pa. Find the temperature when volume and pressure become half of their initial values.

Ans:

Question 19.

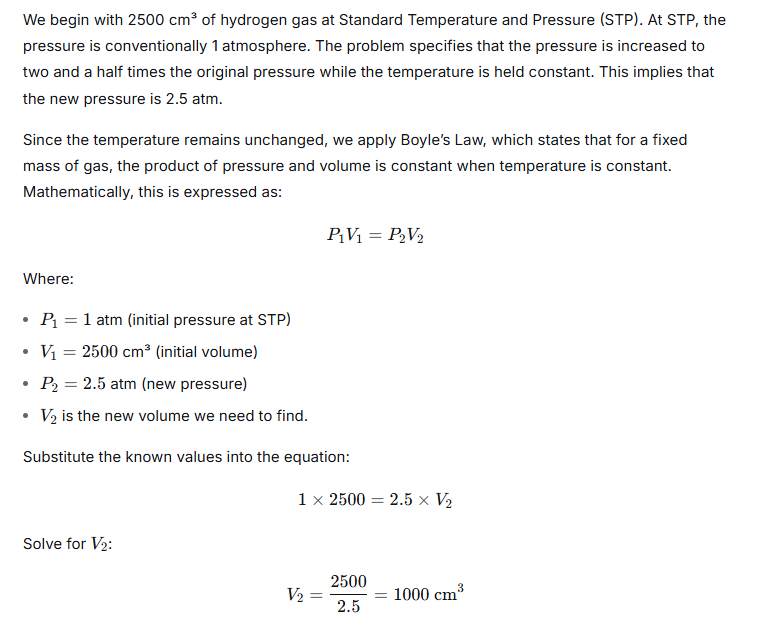

2500 cm3 of hydrogen is taken at STP. The pressure of this gas is further increased by two and a half times (temperature remaining constant). What volume will hydrogen occupy now

Ans:

When you halve both the volume and the pressure of a gas, the combined effect on temperature is significant. Since pressure and volume are both directly proportional to temperature (when other factors are held constant), reducing each by half multiplies together. Mathematically, starting from the ideal gas relationship, halving the volume would tend to increase the temperature if pressure were constant, but halving the pressure would tend to decrease it if volume were constant. The net result is that the absolute temperature is reduced to one quarter of its original value.

Your calculation shows this perfectly: Starting at 300 K, a quarter gives 75 K. Converting that to Celsius by subtracting 273 yields the final result of –198 °C. So, your final answer is accurate. The gas cools dramatically because the drop in pressure has a stronger combined effect than the reduction in volume.

Question 20.

Taking the volume of hydrogen as calculated in Q.19, what change must be made in Kelvin (absolute) temperature to return the volume to 2500 cm3 (pressure remaining constant)?

Ans:

To solve this, we apply Charles’s Law, which states that at constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature (Kelvin). This is expressed as V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂.

Let’s denote the volume calculated in Q.19 as V₁ cm³ and its corresponding temperature as T₁ Kelvin. We want the new volume V₂ to be 2500 cm³ at a new temperature T₂, with pressure constant. According to the law:

T₂ = (V₂ / V₁) * T₁ = (2500 / V₁) * T₁.

The change in Kelvin temperature required is therefore:

ΔT = T₂ – T₁ = T₁ * (2500 / V₁ – 1).

To get a numerical answer, you would substitute the specific values for V₁ and T₁ from your Q.19. The key is to remember that the temperature must be in Kelvin for this calculation to be valid, and the change is found by first calculating the new temperature (T₂) using the ratio of the volumes and then subtracting the original temperature (T₁). The pressure, as stated, remains constant throughout this change.

Question 21.

A given amount of gas A is confined in a chamber of constant volume. When the chamber is immersed in a bath of melting ice, the pressure of the gas is 100 cmHg.

What is the temperature when the pressure is 10cmHg?

What will be the pressure when the chamber is brought to 100°C

Ans:

This problem involves a fixed amount of gas confined at a constant volume. Under these conditions, the gas obeys Gay-Lussac’s Law, which states that the pressure of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature (in Kelvin). The formula is P₁/T₁ = P₂/T₂, where temperatures must be in Kelvin.

For the first part, the initial conditions are: Pressure P₁ = 100 cmHg, Temperature T₁ = 0°C = 273 K. We need the temperature T₂ when pressure P₂ = 10 cmHg. Applying the law: 100/273 = 10/T₂. Solving gives T₂ = (10 * 273) / 100 = 27.3 K. Converting back to Celsius: 27.3 K – 273 = -245.7°C. Therefore, the temperature when the pressure is 10 cmHg is a very cold -245.7°C.

For the second part, we find the new pressure (P₃) when the chamber is at T₃ = 100°C = 373 K. Using the initial conditions again (P₁=100 cmHg, T₁=273 K): 100/273 = P₃/373. Solving gives P₃ = (100 * 373) / 273 ≈ 136.63 cmHg. Thus, when heated to 100°C, the pressure inside the chamber increases to approximately 136.6 cmHg.

Question 22.

A gas is to be filled from a tank of capacity 10,000 litres into cylinders each having capacity of 10 litres. The condition of the gas in the tank is as follows:

The pressure inside the tank is 800 mm of Hg.

The temperature inside the tank is −3°C.

When the cylinder is filled, the pressure gauge reads 400 mm of Hg and the temperature is 270 K. Find the number of cylinders required to fill the gas.

Ans:

Question 23.

Calculate the volume occupied by 2 g of hydrogen at 27°C and 4-atmosphere pressure if at STP it occupies 22.4 litres.

Ans:

We start with the known fact that one mole of any gas occupies 22.4 liters under Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP), defined as 0°C (273 K) and 1 atmosphere of pressure. Since 2 grams of hydrogen gas (H₂) equals one mole, its initial volume is 22.4 L under these standard conditions.

The problem asks us to find the new volume when this same amount of gas is subjected to a temperature of 27°C and a pressure of 4 atm. First, we convert the Celsius temperature to the absolute Kelvin scale, which is essential for gas law calculations. Thus, 27°C becomes 300 K (27 + 273). The relationship between pressure, volume, and temperature for a fixed amount of gas is governed by the combined gas law: (P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂.

Plugging in our known values—P₁ = 1 atm, V₁ = 22.4 L, T₁ = 273 K, P₂ = 4 atm, and T₂ = 300 K—we set up the equation: (1 × 22.4) / 273 = (4 × V₂) / 300. Solving for the unknown V₂ involves cross-multiplication. This gives us 4V₂ = (22.4 × 300) / 273. Performing the arithmetic, 22.4 multiplied by 300 equals 6720. Dividing 6720 by 273 yields approximately 24.615. Finally, dividing this result by 4 provides the new volume.

Therefore, the final volume occupied by the 2 grams of hydrogen gas under the new conditions is approximately 6.15 liters. This reduction from the original 22.4 liters is expected, as the significant increase in pressure dominates the effect of the modest increase in temperature, causing the gas to be compressed into a smaller space.

Question 24.

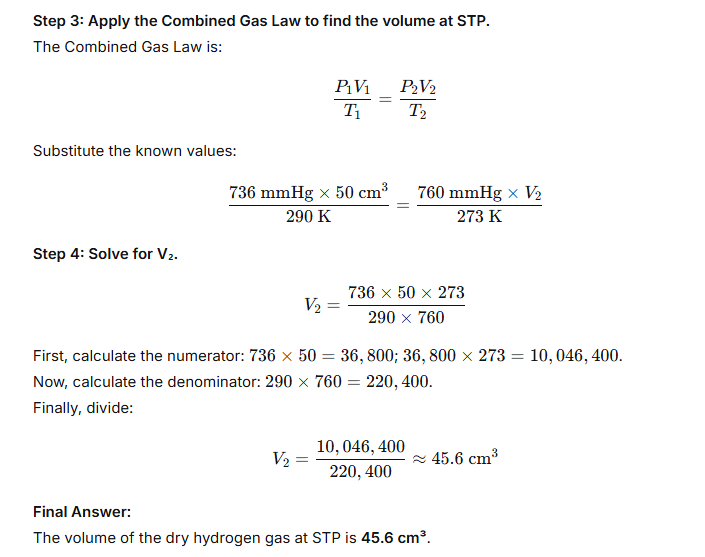

50 cm3 of hydrogen is collected over water at 17°C and 750 mmHg pressure. Calculate the volume of a dry gas at STP. The water vapour pressure at 17°C is 14 mmHg.

Ans:

Question 25.

Which will have greater volume when the following gases are compared at STP:

1.2/N2 at 25°C and 748 mmHg

1.25/O2 at STP

Ans:

To compare the volumes fairly, we must first bring both gas samples to the same standard conditions of temperature and pressure (STP: 0°C or 273 K, and 760 mmHg).

We start with the nitrogen sample. Its initial volume is 1.2 L at 25°C (which is 25 + 273 = 298 K) and 748 mmHg pressure. To find its volume at STP, we apply the combined gas law: (P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂. Rearranging to solve for the STP volume (V₂) gives us V₂ = (P₁V₁T₂) / (P₂T₁). Substituting the values: V₂ = (748 mmHg * 1.2 L * 273 K) / (760 mmHg * 298 K). Performing this calculation yields a volume of approximately 1.08 L for nitrogen at STP.

The oxygen sample, however, is already at STP with a given volume of 1.25 L. No conversion is needed. Therefore, when directly compared under identical STP conditions, the oxygen sample occupies 1.25 L, while the nitrogen sample occupies only about 1.08 L. Consequently, the 1.25 L of O₂ at STP has the greater volume.

Question 26.

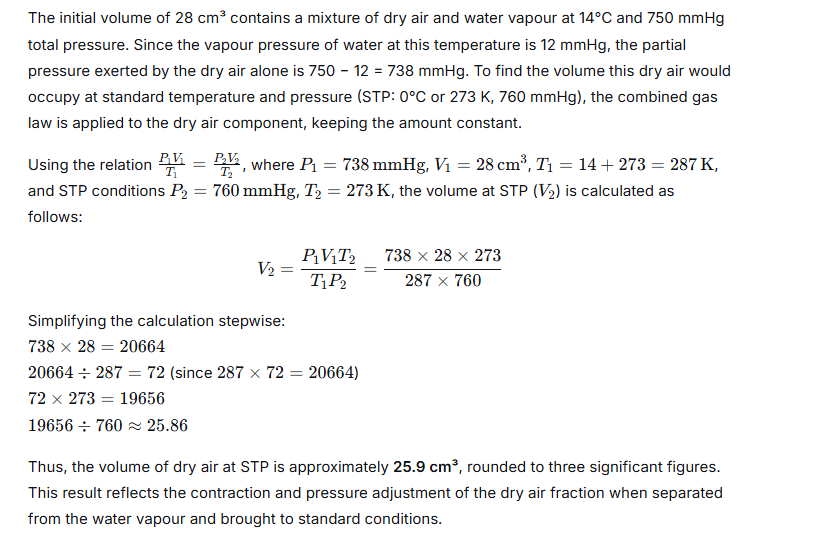

Calculate the volume of dry air at STP that occupies 28 cm3 at 14°C and 750 mmHg pressure when saturated with water vapour. The vapour pressure of water at 14°C is 12 mmHg.

Ans:

Question 27.

An LPG cylinder can withstand a pressure of 14.9 atmospheres. The pressure gauge of the cylinder indicates 12 atmospheres at 27°C. Because of a sudden fire in the building, the temperature rises. At what temperature will the cylinder explode?

Ans:

Based on the principle of Gay-Lussac’s Law for gases at constant volume, the pressure of a fixed mass of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature. This means that as the temperature of the LPG inside the sealed cylinder increases, its pressure will increase proportionally.

We are given:

- Maximum safe pressure, P₂ = 14.9 atm

- Initial pressure, P₁ = 12 atm

- Initial temperature, T₁ = 27 °C = 300 K (converted to Kelvin by adding 273)

- We need to find the explosion temperature, T₂ in °C.

Applying the formula P₁/T₁ = P₂/T₂, we rearrange to solve for T₂:

T₂ = (P₂ × T₁) / P₁

Substituting the values:

T₂ = (14.9 atm × 300 K) / 12 atm

T₂ ≈ 372.5 K

Converting this back to Celsius:

T₂ = 372.5 K – 273 = 99.5 °C

Therefore, the cylinder will explode when the internal temperature reaches approximately 100 °C. It is important to note that this calculation assumes no gas leaks and a constant volume. In a real fire scenario, the intense and uneven heating could cause the metal to weaken, potentially leading to failure at a lower temperature. This highlights the extreme danger of leaving pressurized containers like LPG cylinders exposed to fire.

Question 28.

22.4 litres of gas weighs 70 g at STP. Calculate the weight of the gas if it occupies a volume of 20 litres at 27°C and 700 mmHg of pressure.

Ans:

The problem begins with a key piece of information: a volume of 22.4 liters of a specific gas, measured under Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP), has a mass of 70 grams. In chemistry, it is a standard fact that one mole of any gas occupies exactly 22.4 liters at STP. Therefore, the mass given directly corresponds to the molar mass. This means one mole of this gas weighs 70 grams, establishing its molar mass as 70 g/mol.

Next, we need to find the mass of a different sample of the same gas under new, non-standard conditions. This sample has a volume of 20 liters at a temperature of 27°C (which is 300 Kelvin) and a pressure of 700 mmHg. To handle the pressure in the ideal gas law, we convert it into atmospheres: 700 mmHg divided by 760 mmHg/atm gives approximately 0.921 atmospheres. Using the ideal gas equation, PV = nRT, we rearrange it to solve for the number of moles (n). Plugging in the values—P = 0.921 atm, V = 20 L, R = 0.0821 L·atm/mol·K, and T = 300 K—the calculation becomes n = (0.921 * 20) / (0.0821 * 300). Simplifying this step-by-step gives n ≈ 18.42 / 24.63, resulting in approximately 0.748 moles of gas.

Finally, with the number of moles determined and the known molar mass of 70 g/mol, the actual mass of this gas sample is found by simple multiplication. Mass equals moles times molar mass, so 0.748 moles multiplied by 70 g/mol gives a final mass of about 52.36 grams. This is the weight of the 20-liter sample under the specified conditions of temperature and pressure.