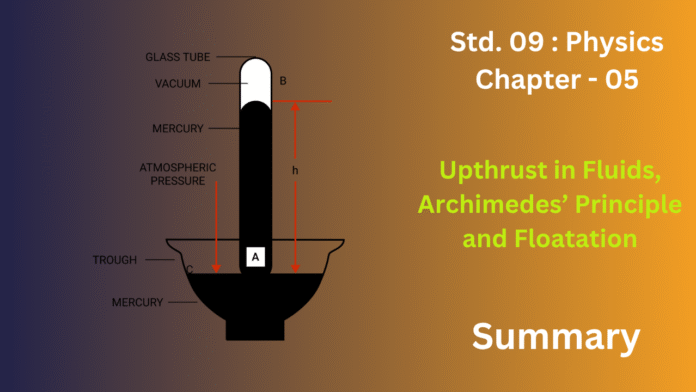

When an object is immersed in a fluid, which can be a liquid or a gas, it experiences an upward force that seems to push against its weight. This upward force is known as upthrust or buoyant force. It occurs because the pressure exerted by a fluid increases with depth. The pressure on the lower surface of the submerged object is greater than the pressure on its upper surface, resulting in a net upward force. The magnitude of this upthrust depends on two key factors: the density of the fluid itself and the volume of the fluid that the object displaces. Essentially, denser fluids and objects with a larger submerged volume will experience a stronger buoyant force.

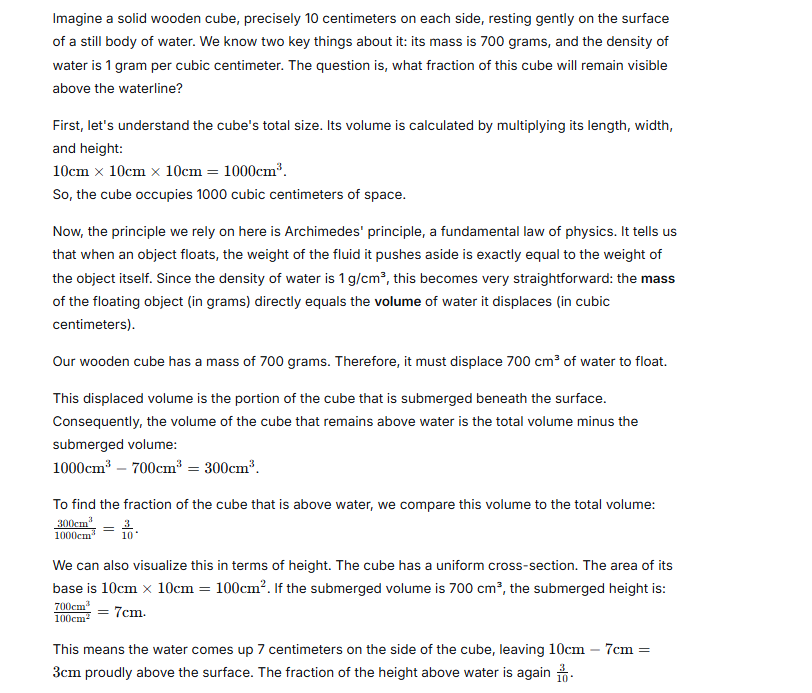

This fundamental observation is perfectly captured by Archimedes’ Principle. It states that when a body is fully or partially immersed in a fluid, it experiences an upthrust equal to the weight of the fluid it has displaced. This means if you could collect the fluid that spills over when an object is submerged, the weight of that fluid would be exactly equal to the buoyant force pushing up on the object. This principle provides the scientific basis for why objects sink or float. Whether an object floats, sinks, or remains suspended is determined by the balance between its own weight and the upthrust acting upon it. An object will float if the upthrust (equal to the weight of displaced fluid) is greater than or equal to the object’s own weight. For a floating body, the weight of the entire object is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by its submerged portion.

The principle of floatation has profound practical applications. It explains how massive steel ships, which are much denser than water, can float. This is achieved by shaping the ship into a hollow form, which increases its volume and displaces a very large amount of water. The weight of this displaced water equals the total weight of the ship and its cargo, allowing it to float. Similarly, submarines control their buoyancy by adjusting the amount of water in their ballast tanks, allowing them to dive or surface. Hot air balloons rise in the air because the hot air inside is less dense than the surrounding cooler air, making the balloon’s weight less than the upthrust from the displaced cooler air.

Exercise 5 (A)

Question 1.

What do you understand by the term upthrust of a fluid? Describe an experiment to show its existence.

Ans:

Understanding Upthrust

In simple terms, upthrust (also known as the buoyant force) is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of an object immersed in it. A fluid can be either a liquid or a gas. This force is why a piece of wood floats on water, a helium balloon rises in the air, or you feel lighter when you’re in a swimming pool.

This phenomenon occurs because pressure in a fluid increases with depth. The bottom of an immersed object experiences a greater fluid pressure than its top. The difference in these pressures creates a net upward force, which we call upthrust.

An Experiment to Demonstrate the Existence of Upthrust

This simple experiment uses common lab equipment to clearly show that a fluid pushes upwards on an object.

Aim: To demonstrate that a fluid (water) exerts an upward force (upthrust) on an object placed in it.

Materials Required:

- A spring balance (or a digital force meter)

- A small, dense object (e.g., a metal weight or a stone)

- A beaker or a large overflow can

- Water

- A thin string or thread

Procedure:

- Setup: Tie the metal weight securely to the hook of the spring balance using the string. Hold the spring balance from the top so that the object hangs freely in the air.

- Measure Weight in Air: Carefully note the reading on the spring balance. This value represents the true weight of the object. Let’s call this reading W₁.

- Prepare the Beaker: Fill the beaker with water until it is almost full. If you are using an overflow can, ensure the spout is clear.

- Immerse the Object: Now, slowly lower the object suspended from the spring balance into the beaker of water. Ensure the object is completely submerged but does not touch the bottom or sides of the beaker.

- Measure Weight in Water: Observe the new reading on the spring balance while the object is still submerged. You will immediately notice that the reading has decreased. Let’s call this new, lower reading W₂.

Observations:

- The spring balance reading in air (W₁) is greater than the reading when the object is submerged in water (W₂).

- This means the object appears to weigh less when it is inside the water.

Explanation and Conclusion:

The apparent loss in weight (W₁ – W₂) is not because the water is “erasing” mass. Instead, the water is exerting an upward force on the object, which counteracts some of the downward pull of gravity. This upward force is the upthrust.

The spring balance measures the net downward force. When the upthrust from the water pushes up, it supports some of the object’s weight, so the spring balance has to pull with less force to hold the object, resulting in a lower reading.

Question 2.

In what direction and at what point does the buoyant force on a body due to a liquid act?

Ans:

The buoyant force, often called upthrust, is the upward force exerted by a fluid (a liquid or a gas) that opposes the weight of an object immersed in it. To answer your question precisely:

Direction of the Buoyant Force

The buoyant force always acts vertically upward. This direction is independent of the shape of the object or how it is oriented in the fluid. It is directly opposite to the direction of the effective weight of the fluid, which is downward due to gravity.

Point of Action of the Buoyant Force

The buoyant force acts through a specific point called the Center of Buoyancy.

The Center of Buoyancy is defined as the center of mass of the fluid which would have been there if the object were not present. In simpler terms, it is the geometric center (the centroid) of the immersed portion of the body.

To visualize this:

Imagine you carefully mark the outline of the part of the object that is submerged in the liquid. Now, mentally remove the object and fill that exact submerged volume with the same liquid. The center of mass of that hypothetical, shaped volume of liquid is the center of buoyancy. The buoyant force acts vertically upward through this point.

A Key Distinction

It is crucial to understand that the center of buoyancy is not necessarily the same as the object’s own center of gravity. The center of gravity is a fixed property of the object’s mass distribution, while the center of buoyancy depends entirely on the shape of the submerged volume.

- For a completely and uniformly submerged object (like a sealed box underwater), the center of buoyancy is fixed and coincides with the object’s geometric center.

- For a floating or partially submerged object (like a ship), the center of buoyancy shifts as the object tilts or rolls, because the shape of the submerged volume changes. This shifting is what helps a stable object like a ship right itself.

Question 3.

What is meant by the term buoyancy?

Ans:

At its simplest, buoyancy is the uplifting force, the invisible “lift,” that a fluid gives to an object that is placed in it. Think of the feeling you get when you try to push a beach ball underwater; that powerful push back against your hands is buoyancy at work.

This happens because of a fundamental difference in pressure. A fluid, which can be a liquid like water or a gas like air, has weight and exerts pressure on all sides of an object submerged within it. This pressure increases with depth. So, the bottom of a submerged object experiences a greater upward push from the fluid than the downward push on its top. This difference in pressure results in a net force that points upward. We call this net upward force the buoyant force.

The strength of this buoyant force is governed by a principle discovered by the ancient Greek thinker Archimedes. It states that the buoyant force on an object is equal to the weight of the fluid that the object displaces.

Imagine you carefully lower an object into a full bucket of water. The water that spills out over the edge has a specific weight. Archimedes’ principle tells us that the buoyant force pushing up on the object is exactly equal to the weight of that spilled water.

This is why some things float and others sink:

- An object floats if the buoyant force (weight of displaced fluid) is greater than the object’s own weight. A massive steel ship floats because its hollow shape displaces a huge volume of water, and the weight of that water is greater than the ship’s weight.

- An object sinks if its own weight is greater than the buoyant force it creates. A small, solid steel bolt sinks because it only displaces a little bit of water, and the weight of that water is less than the bolt’s weight.

- An object remains suspended (neutrally buoyant) when the two forces are perfectly balanced.

Question 4.

Define upthrust and state its S.I. unit.

Ans:

Upthrust is the upward force exerted on an object when it is fully or partially submerged in a fluid (a liquid or a gas). This force arises because the pressure in a fluid increases with depth. The pressure on the lower surface of the submerged object is greater than the pressure on its upper surface, resulting in a net upward push. The magnitude of this force is exactly equal to the weight of the fluid that the object displaces, a principle famously established by Archimedes.

For example, when you try to push an empty bucket underwater, you feel this upward push resisting you; that is the upthrust in action.

The S.I. The unit of upthrust is the newton (N). Since upthrust is a type of force, it shares the same standard unit of measurement.

Question 5.

What is the cause of upthrust? At which point can it be considered to act?

Ans:

The Cause of Upthrust

At its heart, upthrust (also known as buoyant force) is caused by a simple imbalance of pressure in a fluid (a liquid or a gas). Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how this works:

- Pressure Increases with Depth: In any fluid, the pressure is not the same at all levels. The deeper you go, the greater the weight of the fluid above, and therefore the higher the pressure. An object submerged in a fluid experiences greater pressure on its lower surfaces than on its upper surfaces.

- The Force from Below is Stronger: Imagine a cube submerged in water. The water pushes against every face of the cube. The force pushing down on the top of the cube is less than the force pushing up on the bottom of the cube because the bottom is at a greater depth and experiences higher pressure.

- The Net Result is an Upward Push: When you add up all these pressure forces from the fluid, the horizontal forces cancel each other out. However, the upward force on the bottom is greater than the downward force on the top. This difference in forces results in a single, net force that acts in the upward direction. This net force is what we call upthrust or buoyancy.

In essence, the fluid is constantly “trying” to push the object upwards because it cannot exert an equal force on all sides due to the pressure gradient caused by gravity.

The Point Where Upthrust is Considered to Act

Upthrust can be considered to act through a single, specific point called the Center of Buoyancy.

- Definition: The Center of Buoyancy is the center of mass of the fluid that the object displaces.

- How to Visualize It: Imagine you magically remove the submerged object and fill the exact space it occupied with the same fluid. The center of mass of that newly-filled, shaped volume of fluid is the center of buoyancy.

- Why This Point? The forces of pressure from the fluid act all over the submerged surface of the object. For the purpose of calculating overall motion and stability, we can simplify this complex distribution of forces into a single, resultant force (the upthrust) acting straight upwards through this one point.

A Practical Example:

Think of a ship. The center of buoyancy is located within the submerged part of the ship’s hull. For the ship to be stable, this center of buoyancy must be positioned correctly relative to the ship’s own center of gravity. If you were to tilt the ship, the center of buoyancy would shift, creating a force that tries to right the ship again.

Question 6.

Why is a force needed to keep a block of wood inside water?

Ans:

It seems strange at first, doesn’t it? If you let a block of wood go above water, it bobs right to the surface. To keep it fully underwater, you have to push down on it. The reason for this isn’t that the wood is “afraid of water,” but rather the result of a constant, invisible tug-of-war between two forces.

The key player here is a force called the buoyant force. You can think of it as a kind of “water lift.” When you submerge the wood, it displaces, or pushes aside, a certain volume of water. The surrounding water pushes back against this from all directions, but the push from the bottom is stronger than the push from the top because pressure increases with depth. This difference in pressure creates a net upward force—that’s the buoyant force.

Now, let’s look at the other team in this tug-of-war: gravity. Gravity is pulling the block of wood straight down towards the center of the Earth. We feel this as the wood’s weight.

Here’s the crucial part: the strength of the buoyant force depends on the weight of the water the block displaces. Wood is less dense than water, meaning for a block of wood and a bucket of water of the same size, the wood is lighter.

So, when the wood is fully submerged, it’s displacing a volume of water that is heavier than the wood itself. This means the upward buoyant force is actually stronger than the downward force of gravity (the wood’s weight).

If the upward force is stronger than the downward force, the object must move upward—and it does! That’s why it floats.

Therefore, to keep the block submerged and stationary, your hand must provide that missing downward force. You are essentially making up the difference. You are adding just enough extra downward pull to balance the powerful upward push of the water, so that the total downward force (gravity + your push) equals the upward buoyant force.

A Simple Summary:

Imagine the block of wood is a spring that is naturally stretched out. Pushing it underwater is like compressing that spring. The moment you let go, the spring (the buoyant force) pushes it back to its natural, resting position—the surface. Your hand is simply the clamp that holds the compressed spring in place.

Question 7.

A piece of wood if left under water comes to the surface. Explain the reason.

Ans:

We’ve all seen it happen: you try to push a piece of wood down into a pond or a bathtub, and the moment you let go, it pops right back up to the surface. This isn’t just a quirky trait of wood; it’s a classic demonstration of a fundamental force of nature.

The main reason for this is a simple battle of density.

Think of density as how much “stuff” is packed into a certain space. Water has a certain density. A piece of wood, by its very nature, is made of fibers and has tiny air pockets trapped inside it. This means that, on average, the same volume of wood is less dense than the same volume of water. It’s lighter for its size.

Now, imagine the wood is fully submerged. The water beneath it is pushing it upward with a force that is equal to the weight of the water the wood has “taken the place of.” This is the buoyant force. Since the wood is less dense, the water it displaces is actually heavier than the wood itself.

So, the upward push from the displaced water is stronger than the downward pull of the wood’s own weight. This net upward force is what we experience as buoyancy. The wood is literally being pushed to the surface by the water around it because it’s a lighter imposter in the water’s space.

It will keep rising until it reaches a point of balance. This is when part of the wood is above the surface. At this stage, the volume of water it’s still displacing (the part that is underwater) now has a weight exactly equal to the weight of the entire piece of wood. The forces are balanced, and it floats peacefully.

For a clear contrast, a stone is much denser than water. The weight of the water it displaces is less than its own weight, so the downward pull wins, and it sinks.

In short, wood floats because it is naturally less dense than water, causing the surrounding water to exert a stronger upward force than the wood’s own downward weight, pushing it to the surface until a perfect balance is found.

Question 8.

Describe an experiment to show that a body immersed in a liquid appears lighter than it really is.

Ans:

Experiment: Discovering the “Vanishing” Weight

Aim: To demonstrate that when a body is submerged in a liquid, it experiences an upward force that makes it appear lighter than its actual weight.

The Core Idea: Imagine lifting a heavy rock. Now, try lifting that same rock from the bottom of a swimming pool. It feels surprisingly easier! This experiment allows us to measure that “missing” weight and understand where it goes.

What You’ll Need:

- A spring balance (or a digital kitchen scale that can be suspended from a stand).

- A solid, non-absorbent object that is heavier than water and can be easily hung (e.g., a small metal weight, a stone tied with a string, or a dense piece of plastic).

- A transparent beaker or a tall measuring jug.

- Water.

- A strong string.

- A retort stand with a clamp (or any creative way to hang the spring balance securely over the beaker).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- The Setup: First, set up your retort stand and clamp. Hang the spring balance from it securely. Make sure the beaker is positioned directly underneath the balance, but empty for now.

- Find the True Weight: Tie your chosen object (let’s say a stone) to the hook of the spring balance using the string. Allow it to hang freely in the air. Carefully note down the reading on the spring balance. This is the object’s true weight in air. Let’s call this reading W₁.

- The Submersion: Now, slowly pour water into the beaker until the stone is completely submerged. Do not let the stone touch the bottom or sides of the beaker. It should be hanging freely in the middle of the water.

- Observe the “Apparent Weight”: Look at the spring balance again. You will immediately see that the reading has decreased. Note down this new, lower reading. This is the object’s apparent weight in water. Let’s call this reading W₂.

- Calculate the “Loss” of Weight: The difference between the two readings is the force that made the object appear lighter.

- Loss in Weight = True Weight (W₁) – Apparent Weight (W₂)

A Dramatic Enhancement (The Overflow Can Demonstration):

To make this even more compelling, you can use a special container called an “overflow can.” This is a spouted beaker filled to the very brim with water.

- Repeat the setup, but place an empty, dry beaker under the spout of the overflow can.

- Submerge the stone. As it enters the water, it will displace its own volume of water, which will flow out of the spout and into the empty beaker.

- Now, carefully collect the displaced water from the beaker.

- Weigh this collected water. You will find something remarkable: The weight of the displaced water is exactly equal to the “loss in weight” (W₁ – W₂) you calculated earlier.

What You’ve Discovered:

The experiment clearly shows that a body immersed in a liquid experiences an upward push, known as the buoyant force. This force is responsible for the object appearing lighter. The enhanced part of the experiment proves a fundamental law of physics: The buoyant force is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. This is Archimedes’ Principle in action.

In essence, the liquid is actively pushing up against the object, counteracting gravity and creating the sensation of reduced weight. This is why ships float, swimmers feel buoyant, and that rock in the swimming pool is so much easier to lift.

Question 9.

Will a body weigh more in air or vacuum when weighed with a spring balance? Give a reason for your answer.

Ans:

The Reason: The Missing Buoyant Force

The reason for this is the absence of the buoyant force (or upthrust) exerted by air.

- How a Spring Balance Works: A spring balance measures the actual force (tension) required to support an object. This is different from a beam balance, which compares masses.

- The Effect of Air (Buoyancy): Every object immersed in a fluid (like air) experiences an upward buoyant force. This force is equal to the weight of the air displaced by the object, as stated by Archimedes’ principle.

- When you weigh the body in air, the spring balance only has to provide enough force to counteract the difference between the object’s actual weight (directed downwards) and the buoyant force (directed upwards).

- So, the reading on the balance is: True Weight – Buoyant Force.

- The Effect of a Vacuum: In a vacuum, there is no surrounding air. Therefore, there is no buoyant force acting upwards on the object.

- In this case, the spring balance must provide the full force to counteract the object’s true weight.

- The reading on the balance is the full True Weight.

Question 10.

A metal solid cylinder tied to a thread is hanging from the hook of a spring balance. The cylinder is gradually immersed into the water contained in a jar. What changes do you expect in the readings of the spring balance? Explain your answer.

Ans:

The Changing Reading of the Spring Balance

When the metal cylinder is gradually immersed in water, the reading on the spring balance will decrease steadily until the cylinder is completely submerged. After full immersion, the reading will stabilize and remain constant, regardless of how much deeper it is pushed.

Here is a step-by-step explanation of why this happens:

1. The Starting Point: Cylinder in Air

Initially, the cylinder hangs freely in the air. The spring balance measures the total downward force, which is simply the weight of the cylinder (mass × acceleration due to gravity). At this point, the reading is at its maximum.

2. The Gradual Immersion: The Role of Buoyancy

As the cylinder is lowered into the water, it starts to displace a volume of water equal to the volume of the part of the cylinder that is submerged. This is where Archimedes’ Principle comes into play.

This principle states that an object immersed in a fluid (liquid or gas) experiences an upward buoyant force. The magnitude of this force is exactly equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

- Buoyant Force = Weight of Displaced Water

This buoyant force acts in the upward direction, directly opposing the downward force of gravity (the weight).

3. The Net Force and the Spring Balance Reading

The spring balance does not measure just the weight; it measures the tension in the thread, which is the net force acting on the cylinder.

- Tension in Thread = Weight of Cylinder (downwards) – Buoyant Force (upwards)

As more of the cylinder is immersed, the volume of water it displaces increases. A greater displaced volume means a greater buoyant force.

Since the weight of the cylinder remains constant, a larger buoyant force means a smaller net downward force (tension). Therefore, the spring balance shows a steadily decreasing reading as immersion progresses.

4. The Point of Full Submersion: A Constant Reading

The critical moment occurs when the entire cylinder is just completely under the water surface. At this point, it cannot displace any more water than its own total volume.

- Once fully submerged, the volume of displaced water becomes constant (equal to the total volume of the cylinder).

- Therefore, the buoyant force also becomes constant.

- With both the weight and the buoyant force now constant, the net force (Tension) also becomes constant.

Pushing the cylinder deeper will not change the reading because the volume of water displaced remains the same.

Question 11.

A body dipped into a liquid experiences an upthrust. State two factors on which upthrust on the body depends.

Ans:

A body dipped into a liquid experiences an upthrust. The two factors on which this upthrust depends are:

- The density of the liquid in which the body is immersed. A denser liquid, like salt water, will exert a greater upthrust on the same body compared to a less dense liquid, like fresh water.

- The volume of the body that is submerged in the liquid. A larger submerged portion of the body will displace a greater amount of liquid, resulting in a stronger upthrust force.

Question 12.

How is the upthrust related to the volume of the body submerged in a liquid?

Ans:

Imagine pushing an empty, sealed plastic container into a bucket of water. The deeper you push it, the more forcefully it tries to pop back up. That upward force you feel is the upthrust, also known as the buoyant force. So, what’s really going on here? The secret lies in the amount of water your container is displacing.

The fundamental principle at work is Archimedes’ principle, which states that the upthrust on an object submerged in a fluid is equal to the weight of the fluid the object displaces.

Now, let’s connect this to volume. The weight of the displaced fluid is directly determined by its volume. We know that:

Weight = Mass × Gravity

and

Mass = Density × Volume

Combining these, we get: Weight of displaced liquid = Density of liquid × Volume displaced × Gravity

Since upthrust equals this weight, the formula becomes:

Upthrust = Density of liquid × Volume submerged × Gravity

This equation reveals the core relationship: The upthrust is directly proportional to the volume of the body submerged in the liquid.

Let’s break down what this means in practical terms:

- Direct Proportionality: If you double the submerged volume of an object, you double the amount of liquid it displaces. Doubling the displaced liquid means doubling its weight, and therefore, the upthrust also doubles. If you submerge only half the volume, you get only half the upthrust.

- Complete vs. Partial Submersion:

- For an object that is completely submerged (like a rock sunk to the bottom of a pond), its entire volume is displacing liquid. Since the submerged volume cannot increase further, the upthrust remains constant no matter how deep it goes (assuming the liquid’s density is uniform).

- For a floating object (like a ship or a swimming person), the submerged volume is only a part of the total object’s volume. As the object settles, it submeres just enough volume so that the upthrust exactly equals its own total weight. A heavier ship sinks deeper, increasing its submerged volume to generate a greater upthrust to balance its weight.

A Simple Thought Experiment:

Think of two identical balloons, one fully inflated and the other only half-inflated. If you push both completely under water, the fully inflated balloon has a much larger volume submerged. It will experience a much stronger push upwards because it displaces a much greater weight of water.

Question 13.

A bunch of feathers and a stone of the same mass are released simultaneously in air. Which will fall faster and why? How will your observation be different if they are released simultaneously in vacuum?

Ans:

In Air: The Stone Falls Faster

When released in air, the stone will fall and hit the ground significantly faster than the bunch of feathers.

Why?

The reason is air resistance. While gravity pulls both objects downward with the same force (because they have the same mass), the air pushes back against them with different amounts of force.

- The Stone: It is very dense and compact. Its small surface area means it has to push aside only a little bit of air as it falls. The upward force of air resistance acting on it is very small compared to the downward pull of gravity. Therefore, it accelerates quickly and reaches a high speed.

- The Bunch of Feathers: It has a very large and irregular surface area. As it falls, it has to push aside a huge amount of air. This creates a very large upward force of air resistance. This force almost immediately balances out the downward force of gravity, causing the feathers to reach a very low terminal velocity very quickly and then float down slowly.

Think of it like this: The stone is like a sleek diver entering water, while the feathers are like an open parachute. The parachute is designed to maximize air resistance, which is exactly what the feathers do naturally.

In Vacuum: They Fall at the Exact Same Speed

If you could perform this experiment inside a vacuum chamber (a space with all the air removed), the observation would be completely different. Both the feathers and the stone would fall at the exact same rate and hit the ground at the exact same time.

Why?

In a vacuum, there is no air. Therefore, the factor that was holding the feathers back—air resistance—is completely eliminated. Since they have the same mass, gravity pulls them with the same force, causing them to accelerate downwards at the same rate (approximately 9.8 m/s² on Earth).

This demonstrates a fundamental principle of physics first proposed by Galileo: all objects, regardless of their mass or composition, will fall with the same acceleration in the absence of air resistance. The mass of the object does not affect its rate of fall because a more massive object is both harder to accelerate (has more inertia) and is pulled by a stronger gravitational force; these two effects cancel each other out perfectly.

Question 14.

A body experiences an upthrust F1 in river water and F2 in sea water when dipped up to the same level. Which is more, F1 or F2? Give a reason.

Ans:

When an object is submerged to an equal depth in two different liquids, the buoyant force acting on it, also known as upthrust, varies. In this case, the upthrust in sea water (F2) is greater than the upthrust in river water (F1).

This difference occurs due to the fundamental principle of buoyancy, established by Archimedes. The principle states that any object, either partially or entirely immersed in a fluid, is acted upon by an upward force equivalent to the weight of the fluid it displaces.

This relationship is expressed by the formula:

Upthrust = Volume of displaced fluid × Density of the fluid × Acceleration due to gravity

Since the object is dipped to the same level in both river water and sea water, the volume of fluid displaced remains constant. The acceleration due to gravity is also a constant factor in this scenario.

Consequently, the density of the fluid becomes the sole determining variable for the magnitude of the upthrust. Sea water possesses a higher density because it contains a substantial concentration of dissolved salts and minerals. In contrast, river water is fresh water and has a comparatively lower density due to the minimal presence of these dissolved substances.

Because the density of sea water is greater than that of river water, and the displaced volume is identical, the weight of the sea water displaced is also greater. It follows that the upward force experienced by the object in the denser sea water, F2, is stronger than the force F1 experienced in the less dense river water.

Question 15.

A small block of wood is completely immersed in (i) water, (ii) glycerine and then released. In each case, what do you observe? Explain the difference in your observation in the two cases.

Ans:

(i) When immersed in water and released:

You would observe that the small block of wood, after being released, initially moves upwards quickly. It shoots through the water, breaks the surface, and then bobs for a moment before coming to rest floating with a significant part of its volume above the water surface. Only a portion of the block remains submerged.

(ii) When immersed in glycerine and released:

In this case, the block of wood would also move upwards when released, but its motion would be noticeably slower and more sluggish compared to its movement in water. It will still break the surface and float, but it will settle such that a much larger portion of its volume remains submerged below the glycerine surface. It sits lower in the glycerine compared to in water.

Explanation of the Difference in Observation:

- The difference in these two behaviors stems from a difference in the density of the two liquids.

- The Principle of Buoyancy: According to Archimedes’ principle, when an object is placed in a fluid, it experiences an upward buoyant force. An object will float if this buoyant force is greater than or equal to the object’s own weight.

- The Role of Density: The wood has a density less than both water and glycerine, which is why it floats in both. However, glycerine is significantly denser and heavier than water.

- Why the Block Floats Higher in Water:

In water, the wood must displace a certain volume of water to generate a buoyant force equal to its weight. Since water is less dense, a relatively large volume of it needs to be displaced to match the wood’s weight. This results in a significant part of the wooden block rising above the surface to achieve this balance, leaving a smaller portion submerged.

- Why the Block Floats Lower in Glycerine:

Because glycerine is denser, a much smaller volume of it has the same weight. Therefore, the wooden block only needs to displace a small volume of glycerine to create a buoyant force equal to its own weight. To displace this smaller volume, a larger portion of the block’s volume must remain submerged. Consequently, it floats much lower in the glycerine.

A Simple Analogy: Imagine you need to lift a 1 kg weight. If you use light, fluffy feathers, you would need a very large basketful of them to weigh 1 kg. But if you use lead shot, you would only need a small cupful to reach 1 kg. The wood is like the “container,” and it only needs to “hold” a small volume of the “heavy” fluid (glycerine) or a large volume of the “light” fluid (water) to achieve the same “weight” (buoyant force).

Question 16.

A body of volume V and density ρ is kept completely immersed in a liquid of density ρL. If g is the acceleration due to gravity, then write expressions for the following:

(i) The weight of the body, (ii) The upthrust on the body,

(iii) The apparent weight of the body in liquid, (iv) The loss in weight of the body.

Ans:

Taking g as the acceleration due to gravity, the required expressions are as follows:

(i) The weight of the body

The weight of a body is the force of gravity acting on it, given by the product of its mass and gravitational acceleration. Since mass (m) = density (ρ) × volume (V), the expression is:

Weight = ρVg

(ii) The upthrust on the body

The upthrust, or buoyant force, is equal to the weight of the liquid displaced by the body. As the body is completely immersed, the volume of liquid displaced is equal to the volume of the body (V). The mass of the displaced liquid is ρ_LV, so the upthrust is:

Upthrust = ρ_LVg

(iii)

The apparent weight is the measured weight of the body when it is submerged. It is equal to the actual weight minus the upthrust force. Therefore, the expression is:

Apparent Weight = Weight – Upthrust = ρVg – ρ_LVg = Vg(ρ – ρ_L)

(iv) The loss in weight of the body

The loss in weight is the difference between the weight of the body in air and its apparent weight in the liquid. This difference is numerically equal to the upthrust acting on it.

Loss in Weight = Weight – Apparent Weight = Upthrust = ρ_LVg

Question 17.

A body held completely immersed inside a liquid experiences two forces:

(i) F1, the force due to gravity and

(ii) F2, the buoyant force.

Draw a diagram showing the direction of these forces acting on the body and state the condition when the body will float or sink.

Ans:

Diagram Description

Imagine a simple, solid cube completely submerged in a liquid, contained within a beaker.

- Force F1 (Force due to Gravity): This is the weight of the body. It is represented by a vertical arrow pointing downwards, starting from the center of the cube. This arrow is labeled F₁.

- Force F2 (Buoyant Force): This is the upward force exerted by the liquid. It is represented by a vertical arrow pointing upwards, also starting from the center of the cube. This arrow is slightly longer than F1 to visually represent a case where the body might rise, and it is labeled F₂.

(Since I cannot create an image, please draw this based on the description above. The key is that both forces act through the center of the body but in opposite directions.)

Condition for the Body to Sink or Float

The motion of the body is determined by the relative magnitudes of these two forces.

1. Condition for Sinking:

The body will sink if the downward force due to gravity is greater than the upward buoyant force.

In other words:

F₁ > F₂

This happens when the density of the body is greater than the density of the liquid it is immersed in. Its weight is simply too great for the buoyant force to support.

2. Condition for Floating:

The body will float if the upward buoyant force is greater than or equal to the downward force due to gravity.

In other words:

F₂ ≥ F₁

More precisely:

- If F₂ > F₁, the body will accelerate upwards and rise to the surface. Once it reaches the surface, it will float partially immersed until the buoyant force from the displaced liquid equals its weight (F₂ = F₁).

- If F₂ = F₁ right from the start, the body will remain in equilibrium at any submerged depth. This means the density of the body is equal to the density of the liquid.

Question 18.

1. Complete the following sentence : Two balls, one of iron and the other of aluminium experience the same upthrust when dipped completely in water if _____________ .

2. Complete the following sentence : An empty tin container with its mouth closed has an average density equal to that of a liquid. The container is taken 2 m below the surface of that liquid and is left there. Then the container will ____________ .

3. Complete the following sentence : A piece of wood is held under water. The upthrust on it will be ___________ the weight of the wood piece.

Ans:

1. Two balls, one of iron and the other of aluminium, experience the same upthrust when dipped completely in water if their volumes are equal.

Reasoning: The buoyant force acting on an object submerged in a fluid is determined by the amount of fluid it displaces, not by the object’s own material composition. This is the essence of Archimedes’ principle. Since both balls are fully immersed and have identical volumes, they push aside the exact same amount of water. The water exerts an upward force equal to the weight of this displaced volume. Whether that space is occupied by dense iron or lighter aluminium is irrelevant to the water; the reaction force depends solely on the volume of water moved. Consequently, the upward push, or upthrust, is identical for both spheres.

2. An empty tin container with its mouth closed has an average density equal to that of a liquid. The container is taken 2 m below the surface of that liquid and is left there. Then the container will remain at rest at that location.

Reasoning: An object will achieve a state of neutral buoyancy—neither sinking nor rising—when its overall density matches that of the surrounding fluid. In this case, the container’s density is equal to the liquid’s density. This balance means the downward force of gravity on the container is exactly countered by the upward buoyant force from the displaced liquid. With these two opposing forces cancelling each other out, the net force on the container is zero. According to fundamental physics, an object with no net force acting upon it will not accelerate. Therefore, the container has no tendency to move and will remain stationary at the 2-meter depth where it was released.

3. A piece of wood is held under water. The upthrust on it will be greater than the weight of the wood piece.

Reasoning: Wood is naturally less dense than water, which is why it floats. When floating freely, it settles so that the portion below the surface displaces a volume of water whose weight equals the wood’s entire weight. However, when the wood is pushed and held completely underwater, it is forced to displace a volume of water equal to its own total volume. This total volume is greater than the submerged volume it has when floating. Since the upthrust equals the weight of the actual displaced water, this force becomes greater than the wood’s weight. This is the reason you must apply a continuous downward force to keep it submerged; you are counteracting this excess buoyant force that wants to push the wood back to the surface.

Question 19.

Prove that the loss in weight of a body when immersed wholly or partially in a liquid is equal to the buoyant force (or upthrust) and this loss is because of the difference in pressure exerted by liquid on the upper and lower surfaces of the submerged part of body.

Ans:

Proof of Archimedes’ Principle Based on Fluid Pressure

The observation that a body immersed in a fluid experiences an upward force, leading to an apparent loss of weight, is a fundamental concept in fluid mechanics. This can be rigorously proven by examining the forces exerted by the fluid pressure on the submerged body.

Part 1: Establishing the Scenario

Consider a solid body of an arbitrary shape submerged in a fluid of density (ρ). To analyze the forces, we will use a thought experiment involving a simpler object.

Imagine a right circular cylinder with a cross-sectional area (A) and height (h) submerged in the fluid such that its top and bottom faces are horizontal. The top face is at a depth of (h₁) below the free surface of the fluid, and the bottom face is at a depth of (h₂). Therefore, the height of the cylinder is (h = h₂ – h₁).

Part 2: Analyzing the Forces Due to Fluid Pressure

The fluid pressure at any depth is given by (P = P₀ + ρgh), where (P₀) is the atmospheric pressure.

- Force on the Top Face:

- Pressure at the top face, (P₁ = P₀ + ρgh₁)

- This force acts downward (perpendicular to the surface).

- Force (F₁) = Pressure × Area = (P₁ × A) = (P₀ + ρgh₁)A

- Force on the Bottom Face:

- Pressure at the bottom face, (P₂ = P₀ + ρgh₂)

- This force acts upward.

- Force (F₂) = Pressure × Area = (P₂ × A) = (P₀ + ρgh₂)A

- Forces on the Side Walls:

- The horizontal forces on the vertical side walls are equal and opposite at every point at the same depth. Therefore, they cancel each other out completely, resulting in no net horizontal force.

Part 3: Calculating the Net Vertical Force (Buoyant Force)

The net force acting on the cylinder is the vector sum of all the forces. Since the horizontal forces cancel, we only consider the vertical forces.

The downward force is (F₁) and the upward force is (F₂). Therefore, the net upward force (F_b), known as the buoyant force or upthrust, is:

(F_b = F₂ – F₁)

(F_b = [ (P₀ + ρgh₂)A ] – [ (P₀ + ρgh₁)A ])

(F_b = P₀A + ρgh₂A – P₀A – ρgh₁A)

(F_b = ρgA (h₂ – h₁))

Since (h₂ – h₁ = h), the height of the cylinder, we get:

(F_b = ρg A h)

Now, note that (A × h) is the volume of the cylinder, which is equal to the volume of the fluid displaced by the cylinder, (V_d).

Therefore,

F_b = ρg V_d

But (ρ × V_d) is the mass of the fluid displaced, and (ρg V_d) is the weight of the fluid displaced.

Hence, we have shown that:

Buoyant Force (F_b) = Weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

This is the formal statement of Archimedes’ principle.

Part 4: Connecting to Loss of Weight and Pressure Difference

- Loss in Weight: When the cylinder is suspended in the fluid, two main vertical forces act on it:

- Its actual weight (W_actual = mg) acting downward.

- The buoyant force (F_b) acting upward.

The net force measured by a scale (the apparent weight, W_apparent) is:

(W_apparent = W_actual – F_b)

Therefore, the loss in weight is (W_actual – W_apparent = F_b).

This proves that the loss in weight is numerically equal to the buoyant force.

- Origin in Pressure Difference: As derived in the calculation, the buoyant force (F_b) arose directly from the difference between the upward pressure on the bottom surface and the downward pressure on the top surface.

(F_b = F₂ – F₁ = (P₂ – P₁) × A)

Since (P₂ > P₁) because (h₂ > h₁), the net force is upward. The pressure difference is itself due to the difference in depth (h) and is equal to (ρgh). Thus, the loss in weight is fundamentally because of the difference in pressure exerted by the liquid on the upper and lower surfaces of the submerged part of the body.

Part 5: Generalization to an Arbitrary Shape

While we used a cylinder for simplicity, the principle holds for any shape. Any arbitrarily shaped body can be thought of as being composed of many tiny vertical columns similar to the one analyzed. For each column, the net vertical force is (ρg × volume of the column). The sum of the forces on all these columns is (ρg × total volume of the body), which is the weight of the fluid displaced by the entire body. The horizontal components on the slanted surfaces will always cancel out for the entire object, leaving only a net upward vertical force.

Conclusion

We have proven that for a body immersed in a fluid:

- The loss of weight is exactly equal to the buoyant force (upthrust).

- This buoyant force is numerically equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the body.

Question 20.

A sphere of iron and another sphere of wood of the same radius are held under water. Compare the upthrust on the two spheres.

[Hint: Both have equal volume inside the water].

Ans:

Imagine you have two boxes that are completely identical in size and shape. You fill one with feathers and the other with rocks. Even though the boxes hold the same amount of space, the rock-filled box is obviously much harder to lift. This same basic idea is the key to understanding what happens in water.

Since the two spheres have the same radius, they take up precisely the same amount of space; they have equal volume. The critical difference lies in how much “stuff,” or mass, is packed into that space.

Iron is a very heavy, compact material. A sphere made of it packs a tremendous amount of mass into its volume. In contrast, wood is made of a fibrous, porous material, so a sphere of the same size contains far less mass.

Now, think about what happens when you place an object in water. The water pushes back with a force that is directly related to the amount of water the object displaces. Because the spheres are the same size, the water pushes upward on both of them with an identical force.

This is where the balance tips. For the wooden sphere, the upward push from the water is stronger than the downward pull of the sphere’s own weight. As a result, it is buoyed to the surface and floats.

For the iron sphere, its weight is so immense—because it is so densely packed with mass—that the water’s upward push is simply not enough to hold it. The downward force wins, and the sphere sinks.

Ultimately, it comes down to a simple contest of forces. The water provides a fixed amount of lift for an object of that size. The wooden sphere is light enough to be supported, while the iron sphere is too heavy for that same lift to manage.

Question 21.

A sphere of iron and another of wood, both of same radius are placed on the surface of water. State which of the two will sink? Give a reason for your answer.

Ans:

It all comes down to a simple but powerful contest: the object’s weight pulling it down versus the water’s push holding it up. Even though two spheres are the same size, what they are made of decides the winner of this contest.

Since the spheres share the same radius, they take up precisely the same amount of space. Imagine two identical boxes; one is filled with feathers and the other with rocks. They are the same size, but their contents make one incredibly heavy and the other very light. This is the situation with the iron and wood spheres.

Iron is an inherently heavy, compact material for its size. A sphere of it is very massive. Wood, on the other hand, is light and porous. A sphere of wood of the exact same dimensions has far less mass.

Water has a natural “lifting power.” When you place an object in water, the water tries to hold it up with a force equal to the weight of the water the object displaces. Since our spheres are the same size, they displace the same amount of water, so the water’s lifting push is identical for both.

For the wooden sphere, this upward push from the water is more than enough to support its light weight, so it floats comfortably on the surface. For the iron sphere, its own weight is so much greater than the water’s maximum lifting effort that it wins the contest outright, and the sphere sinks straight to the bottom. In essence, the iron sphere is just too heavy for the amount of water it pushes aside, while the wooden sphere is light enough to be supported.

Question 22.

How does the density of material of a body determine whether it will float or sink in water?

Ans:

What Makes Something Float? It’s All About the Squeeze

We’ve all seen it: a heavy log drifts on a lake while a tiny pebble plummets to the bottom. It seems to defy common sense. The secret isn’t just about weight, but about how tightly packed that weight is. Scientists call this concept density.

A material like lead has a lot of mass crammed into a small box, making it very dense. A material like balsa wood has very little mass in that same box, making it low density.

Here’s the golden rule: An object will float if its material is less dense than the fluid it’s placed in. It will sink if its material is more dense.

Water acts as the benchmark. If an object’s material is “lighter” than water for the same amount of space, it floats. If it’s “heavier,” it sinks.

The Invisible Tug-of-War

To truly get it, picture an invisible battle of forces happening the moment an object touches the water.

- The Downward Pull (Gravity): This is the force you’re most familiar with. It’s the weight of the object itself, pulling it straight down toward the Earth. The more mass the object has, the stronger this pull.

- The Upward Push (The Water’s Pushback): This is the magic force. When an object enters water, it has to push some water out of the way to make space for itself. The water doesn’t like this and pushes back with a force equal to the weight of the displaced water. This is the floating force.

The winner of this tug-of-war decides the object’s fate.

- If the upward push is stronger, the object is forced to the surface and floats.

- If the downward pull is stronger, the object wins and sinks.

Connecting Density to the Battle

This is where it all comes together. Let’s compare two objects of the exact same size—a block of wood and a block of iron.

- The Wood Block: Wood is less dense than water. For its size, it’s relatively light. When it slides into the water, it displaces a volume of water that actually weighs more than the block itself. So, the upward push from the water is stronger than the downward pull of the block’s weight. It floats to the top.

- The Iron Block: Iron is much denser than water. For that same size, it’s incredibly heavy. When it enters the water, the weight of the water it displaces is far less than the weight of the block. The downward pull easily overpowers the upward push, and the block sinks.

The Shape-Shifter Trick: How Heavy Ships Float

This leads to the classic puzzle: “Steel is denser than water, so how does a 500-meter-long ship made of steel float?”

The answer is all about average density. A ship isn’t a solid block of metal; it’s a carefully shaped hollow container filled mostly with air.

While the steel itself is dense, the ship encloses a massive volume of empty space. If you take the entire mass of the ship (the steel, cargo, everything) and divide it by the huge volume it occupies (including all the air inside), you get an average density. This average density is actually lower than that of water. The ship displaces a colossal amount of water, creating an upward push so powerful it can support the ship’s immense weight. A solid steel bar of the same weight, being much more compact, has a much higher average density and sinks immediately.

The Simple Takeaway

At its heart, floating is a contest of heaviness for a given space. Water sets a specific weight limit for every liter of its volume. An object that is less dense stays on top because, for the space it occupies, it’s lighter than the water it displaces. An object that is more dense falls through because it’s heavier. It’s this clever interplay between an object’s density and the water’s powerful pushback that keeps the mightiest vessels afloat.

Question 23.

A body of density ρ is immersed in a liquid of density ρL. State the condition when the body will (i) float and (ii) sink in the liquid.

Ans:

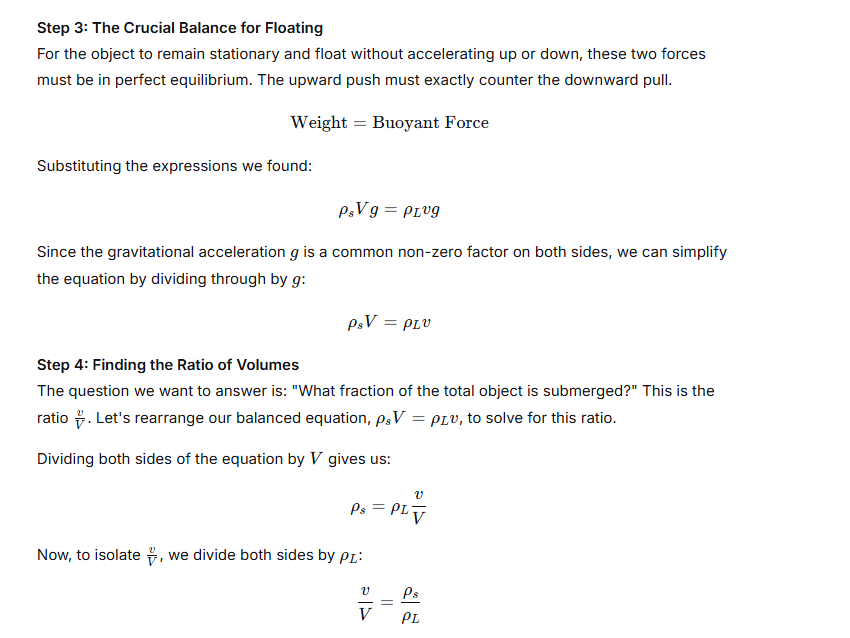

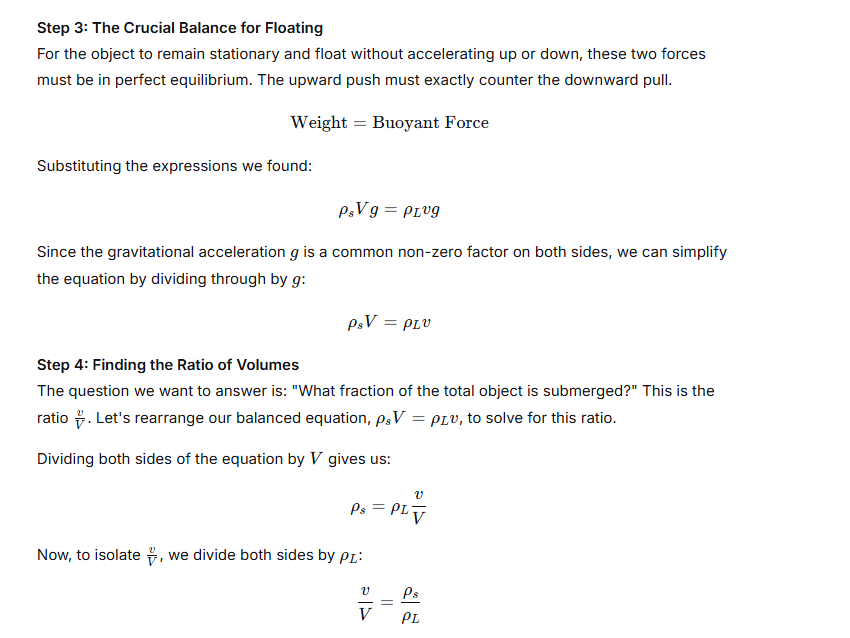

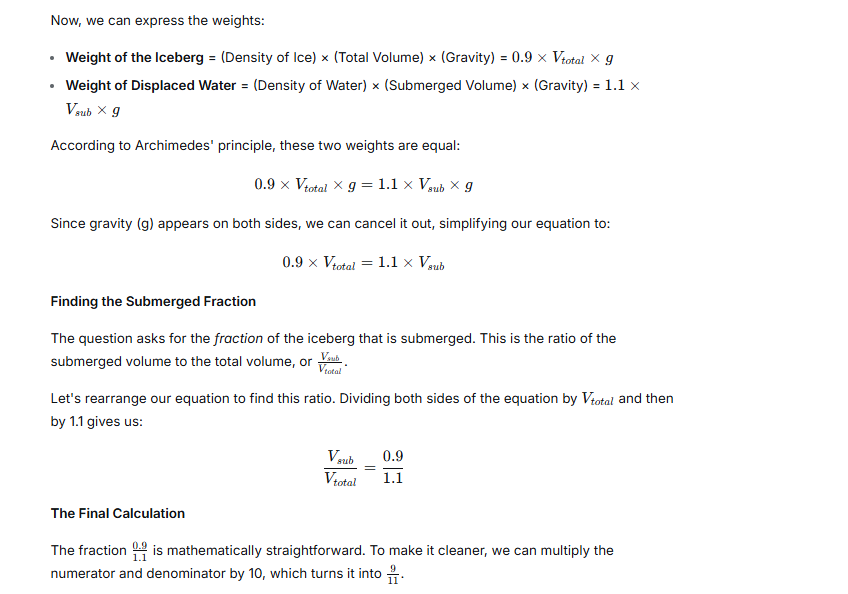

The behavior of a body immersed in a liquid depends on the average density of the body (ρ) relative to the density of the liquid (ρL). The key principle at play is Archimedes’ principle, which states that the buoyant force acting on the body is equal to the weight of the liquid it displaces.

(i) Condition for the body to float:

The body will float when the average density of the body is less than or equal to the density of the liquid (ρ ≤ ρL).

This can be broken down into two scenarios:

- If ρ < ρL, the body will float partially immersed. It will rise and remain at the surface with a portion of its volume above the liquid. In this state, the weight of the liquid displaced by the submerged part is exactly equal to the weight of the entire body.

- If ρ = ρL, the body will float in a state of neutral equilibrium. It will remain at rest completely submerged at any depth within the liquid, as its weight is exactly balanced by the buoyant force.

(ii) Condition for the body to sink:

The body will sink when the average density of the body is greater than the density of the liquid (ρ > ρL).

In this case, the weight of the body is greater than the maximum possible buoyant force (which is the weight of the liquid displaced by the body’s entire volume). Since the downward force (weight) is greater than the upward force (buoyancy), the body experiences a net downward force, causing it to accelerate and sink to the bottom.

Question 24.

It is easier to lift a heavy stone under water than in air. Explain.

Ans:

The experience of a stone feeling lighter when submerged is due to a supporting force provided by the water itself, known as buoyancy. To understand this, we need to consider the forces at play in both air and water.

When you lift a stone in air, you are fighting against a single, dominant force: the downward pull of gravity, which is the stone’s weight. The air, being a gas, is not dense enough to provide any significant upward push to counter this weight. Its effect is so minimal that we disregard it.

The situation changes completely when the stone is underwater. While the stone’s weight due to gravity remains the same, it now must displace, or push aside, a volume of water to make space for itself. The water, being a dense fluid, resists being pushed aside and pushes back against the stone from all directions.

The critical point is that the pressure from the water is greater at the bottom of the stone than at the top because the deeper you go, the greater the water pressure. This difference in pressure results in a net upward force acting on the stone—this is the buoyant force.

Essentially, when you lift the submerged stone, you are no longer lifting its full weight alone. The water is helping you by providing this upward buoyant force. You are only responsible for lifting the stone’s “apparent weight,” which is its true weight minus the weight of the water it displaced. Since a stone is denser than water, it still sinks, but the water’s upward support makes the task of lifting it feel significantly easier. The water is literally helping to hold the stone up.

Question 25.

State the Archimedes’ principle.

Ans:

The behavior of objects immersed in fluids is governed by a fundamental rule discovered long ago. Whether an object floats or sinks is determined not just by its own weight, but by a supportive interaction with the surrounding liquid or gas.

When an item is placed into a fluid, it inevitably occupies space, pushing the fluid out of the way. This displaced volume of fluid is the key to the upward lift, or buoyancy, that the object encounters. The strength of this lifting force is precisely equivalent to the gravitational weight of the fluid that was moved aside. In essence, the fluid “pushes back” with a force equal to what that displaced volume would have weighed.

This concept clarifies how massive, ocean-going vessels stay afloat. A ship’s hull is engineered to be largely hollow, shaping a volume that can displace a tremendous amount of water. The weight of this displaced water creates a powerful upward push that counteracts the ship’s own substantial weight, allowing it to float. On the other hand, a small, solid object like a stone displaces only a minimal volume of water. The resulting buoyant force is a weak upward push, easily overpowered by the stone’s own downward weight, causing it to sink.

Question 26.

Describe an experiment to verify the Archimedes’ principle.

Ans:

Verifying Archimedes’ Principle: The Overflow Can Experiment

Objective: To demonstrate that when an object is submerged in a fluid, it experiences an upward buoyant force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces.

The Core Idea: Archimedes’ principle can feel abstract. This experiment makes it tangible by directly comparing two key measurements:

- The weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

- The apparent loss of weight of the object when submerged (the buoyant force).

If these two values are equal, the principle is verified.

Materials Required:

- Overflow Can (Eureka Can): A specialized container with a spout designed to channel all displaced water into another vessel. A large beaker with a bent tube stuck through a stopper also works.

- Small, dense object: A metal weight or a stone that can be easily suspended. It should be insoluble in water.

- A spring balance or a digital scale: Sensitive enough to measure the small changes in weight.

- A small, lightweight beaker or a cup.

- A tripod stand or a support to hold the overflow can steady (optional, but helpful).

- Water

- A cloth or paper towels for spills.

Experimental Procedure:

Step 1: The Dry Run – Measuring True Weight

- Suspend the object (e.g., the metal weight) from the hook of the spring balance.

- Record its weight in the air. Let’s call this value W₁. This is the true weight of the object.

Step 2: Preparing the Can – The “Full” Mark

- Place the overflow can on a flat surface, with the empty beaker under its spout.

- Slowly pour water into the can until it begins to trickle out of the spout. Wait until the dripping stops completely.

- At this point, remove the beaker (which now contains a small amount of initial overflow) and replace it with your clean, dry, lightweight beaker. The can is now perfectly full and ready.

Step 3: The Submersion – Catching the Displaced Water

- Carefully hold the object suspended from the spring balance over the overflow can, ensuring it is not yet touching the water.

- Gently lower the object until it is completely submerged in the water. Do not let it touch the bottom or sides of the can.

- As the object enters the water, it will displace a volume of water equal to its own volume. This water will flow out through the spout and be collected in the small beaker.

- Once the water stops dripping from the spout, take two readings:

- Read the new weight shown on the spring balance. This is the apparent weight of the object in water. Let’s call this value W₂.

- The buoyant force (B) acting on the object is the weight it has lost: B = W₁ – W₂.

Step 4: The Crucial Weigh-In – Measuring the Displaced Fluid

- Carefully remove the beaker from under the spout, trying not to spill any of the displaced water it has collected.

- Weigh the beaker with the displaced water inside it. Record this mass.

- Now, empty the beaker, dry it thoroughly, and weigh it again to find its empty mass.

- The weight of the displaced water (W_d) is the difference between these two masses, converted to Newtons (if using a scale that measures in grams, multiply the mass in kg by 9.8 m/s² to get weight in Newtons).

Observations and Calculations:

You will now have two key values:

- Buoyant Force (B) = W₁ – W₂

- Weight of Displaced Water (W_d)

Verification and Conclusion:

Compare the calculated buoyant force (B) with the measured weight of the displaced water (W_d).

If Archimedes’ principle is correct, these two values should be very nearly equal.

Within the limits of experimental error (like a tiny water spill, the precision of your scale, or a droplet left in the spout), B ≈ W_d.

This direct, one-to-one relationship confirms that the upward push you feel when lifting a rock in a pond isn’t magic—it’s a force precisely equal to the weight of the water your rock is pushing aside. This is the essence of Archimedes’ principle, and it’s the fundamental reason why steel ships float and hot air balloons rise.

Exercise 5 (A)

Question 1.

A body will experience minimum upthrust when it is completely immersed in :

- Turpentine

- Water

- Glycerine

- Mercury

Question 2.

The S.I. unit of upthrust is :

- Pa

- N

- kg

- kg m2

Question 3.

A body of density ρ sinks in a liquid of density ρL. The densities ρ and ρL are related as :

- ρ = ρL

- ρ < ρL

- ρ > ρL

- Nothing can be said.

Exercise 5 (A)

Question 1.

A body of volume 100 cm3 weighs 5 kgf in air. It is completely immersed in a liquid of density 1.8 × 103 kg m-3. Find: The upthrust due to liquid and The weight of the body in liquid.

Ans:

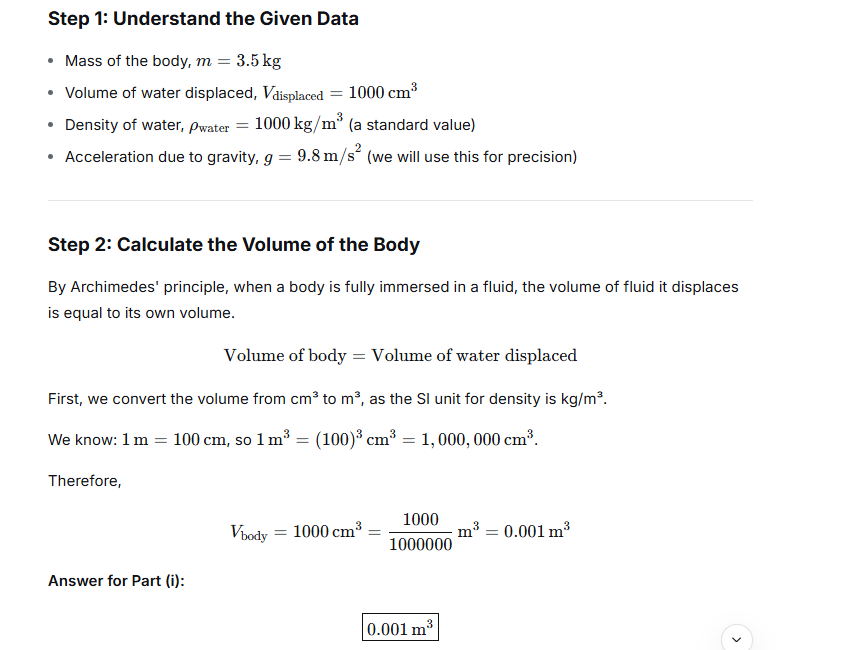

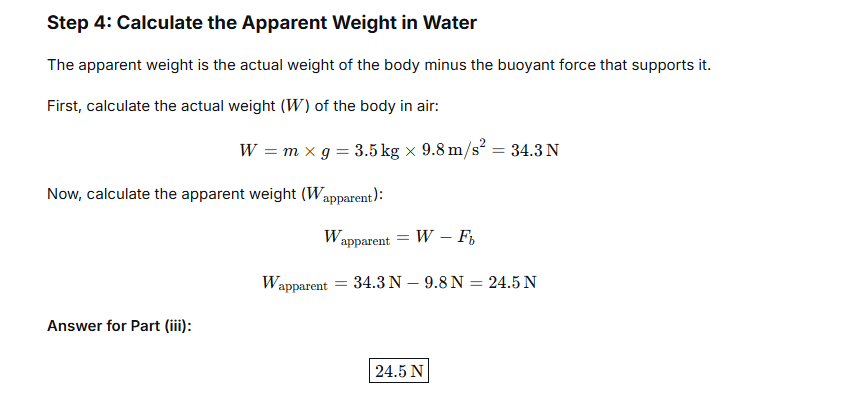

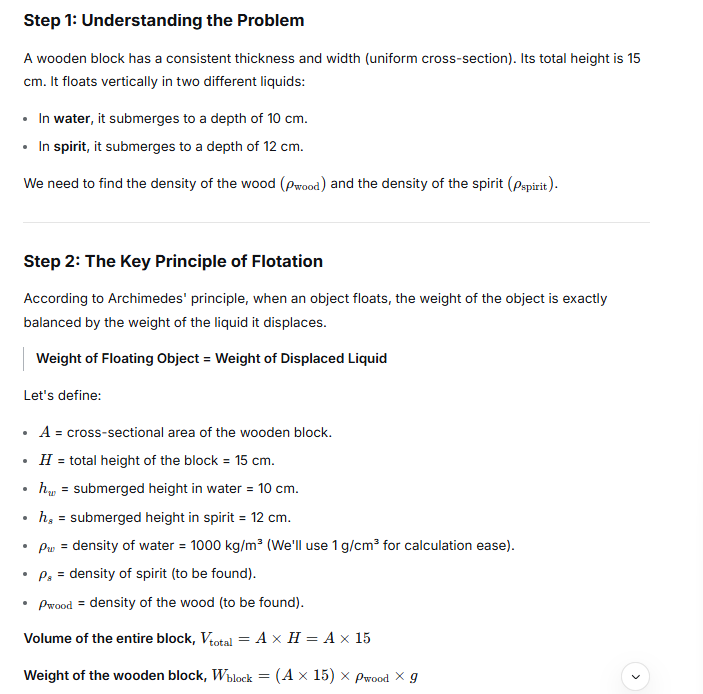

Step 1: Understanding the Problem

We are given a solid object with a volume of 100 cm³. When weighed in air, it registers a weight of 5 kgf. We then immerse it completely in a liquid with a density of 1.8 × 10³ kg/m³. Our goal is to determine the new weight reading of the object when it is submerged in this liquid.

Step 2: Convert the Volume to Consistent Units

The density is provided in kg/m³, so we must convert the object’s volume to cubic meters (m³) for consistency.

100 cm³ = 100 × (10⁻² m)³ = 100 × 10⁻⁶ m³ = 1.0 × 10⁻⁴ m³.

Step 3: Calculate the Buoyant Force (Upthrust)

Archimedes’ principle tells us that the buoyant force acting on the object is equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces.

- Volume of liquid displaced: 1.0 × 10⁻⁴ m³ (equal to the object’s volume).

- Mass of liquid displaced: Volume × Density = (1.0 × 10⁻⁴ m³) × (1.8 × 10³ kg/m³) = 0.18 kg.

- Weight of liquid displaced (Buoyant Force): Since 1 kg has a weight of 1 kgf, the weight of the displaced liquid is 0.18 kgf.

Therefore, the upward buoyant force acting on the object is 0.18 kgf.

Step 4: Determine the Apparent Weight in the Liquid

The weight scale measures the net downward force. When submerged, the buoyant force supports some of the object’s weight, making it seem lighter.

The apparent weight in the liquid is the true weight (in air) minus the buoyant force.

Apparent Weight = Weight in Air – Buoyant Force

*Apparent Weight = 5.00 kgf – 0.18 kgf*

*Apparent Weight = 4.82 kgf*

Final Answer:

The weight of the body when immersed in the liquid is 4.82 kgf.

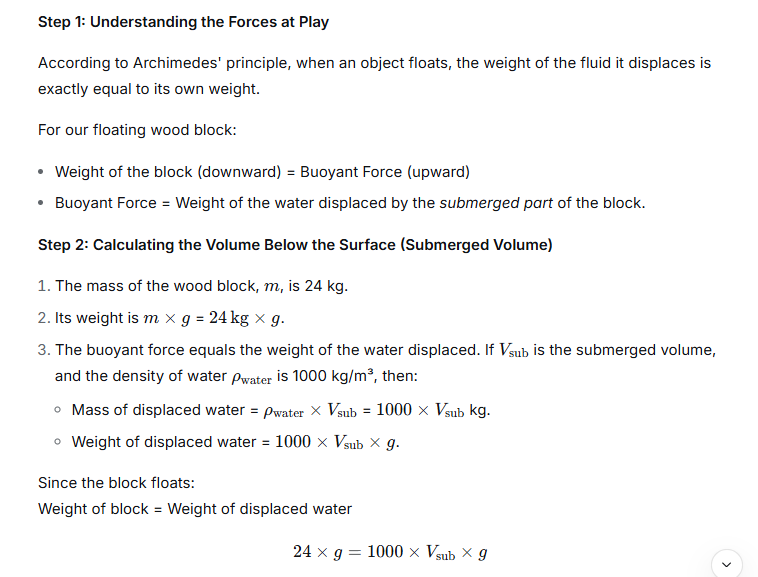

Question 2.

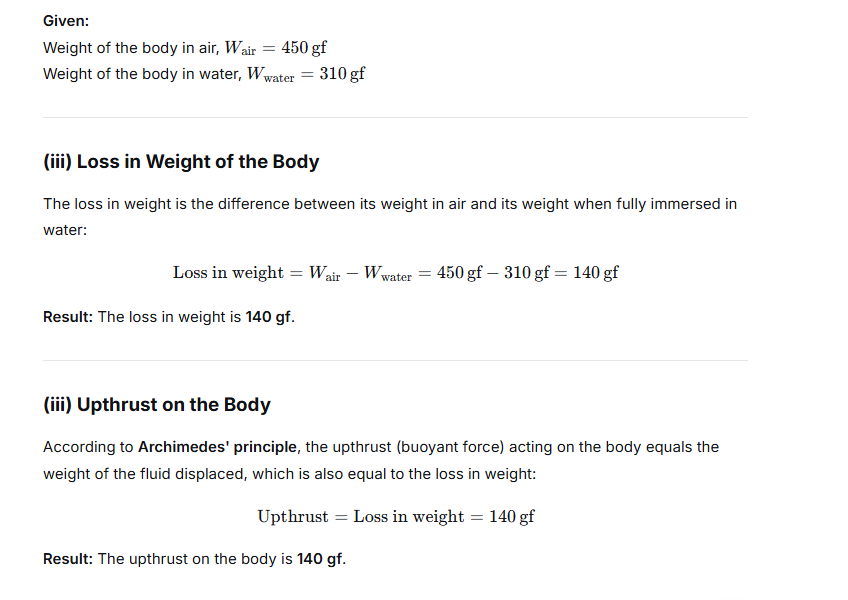

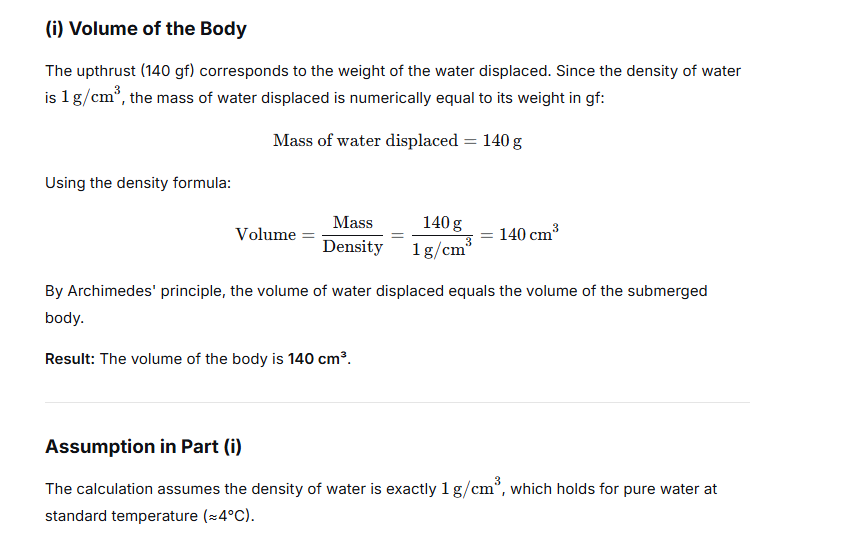

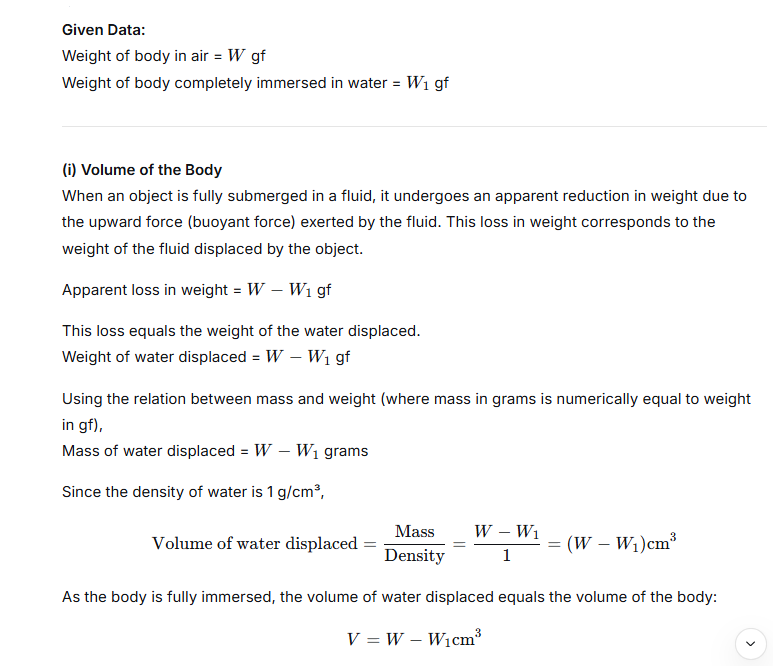

A body weighs 450 gf in air and 310 gf when completely immersed in water. Find

(i) The volume of the body, (ii) The loss in weight of the body, and (iii) The upthrust on the body. State the assumption made in part (i).

Ans:

Question 3.

You are provided with a hollow iron ball A of volume 15 cm3 and mass 12 g and a solid iron ball B of mass 12 g. Both are placed on the surface of water contained in a large tub. Find upthrust on each ball. Which ball will sink? Give a reason for your answer (Density of iron = 8.0 g cm-3)

Ans:

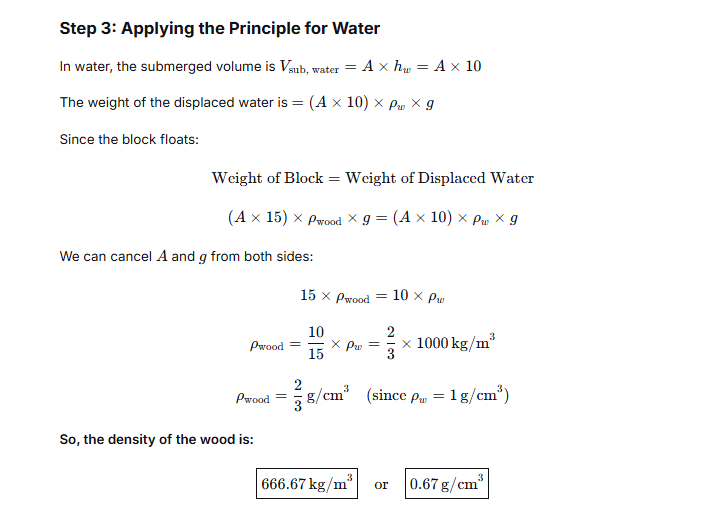

Step 1: Analyze the Two Balls

We have two iron balls placed on water:

- Ball A (Hollow): Mass = 12 g, Total Volume = 15 cm³

- Ball B (Solid): Mass = 12 g

- Density of Iron = 8.0 g/cm³

- Density of Water = 1.0 g/cm³

Step 2: Determine the Upthrust (Buoyant Force) on Each

The upward force, or upthrust, on an object in water is equal to the weight of the water it pushes aside.

For Hollow Ball A:

First, find its overall density:

Overall Density = Mass / Volume = 12 g / 15 cm³ = 0.8 g/cm³

Since its density (0.8 g/cm³) is less than water’s density (1.0 g/cm³), Ball A will float. A floating object displaces a volume of water whose weight equals its own weight.

Therefore, the upthrust on Ball A is equal to its total weight.

Upthrust on A = 12 g-wt

For Solid Ball B:

First, find its actual volume as a solid piece of iron:

Volume = Mass / Density = 12 g / 8.0 g/cm³ = 1.5 cm³

Since its density (8.0 g/cm³) is greater than water’s density (1.0 g/cm³), Ball B will sink. A sinking object is fully submerged, so the upthrust is based on its entire volume.

Upthrust = Density of Water × Volume of Ball × g

= (1.0 g/cm³) × (1.5 cm³) × g

Upthrust on B = 1.5 g-wt

Step 3: Identify Which Ball Sinks and the Reason

Ball B, the solid iron ball, will sink.

Reason:

- Ball A is hollow. The trapped air increases its total volume, making its overall density lower than water. The water can push it up with a force strong enough to support its weight, allowing it to float.

- Ball B is solid and compact. Its high density means it is too heavy for its size. The maximum upward push the water can provide when the ball is completely submerged (1.5 g-wt) is not enough to counter its own weight (12 g-wt). This net downward force causes it to sink.

Question 4.

A solid of density 5000 kg m-3 weighs 0.5 kgf in air. It is completely immersed in water of density 1000 kg m-3. Calculate the apparent weight of the solid in water.

Ans:

When an object is completely immersed in a fluid, it experiences a reduction in its perceived weight. This occurs because of an upward force, known as buoyancy, which counteracts the object’s own weight. The magnitude of this buoyant force is precisely equal to the weight of the fluid that the object pushes aside, or displaces.

Consider a solid object with a weight of 0.5 kilogram-force (kgf) measured in air. Since the unit kgf already incorporates the standard gravitational acceleration, a weight of 0.5 kgf directly indicates a mass of 0.5 kilograms.

The object’s volume can be determined from its mass and its density, which is given as 5000 kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m³). The volume (V) is found using the formula:

V = Mass / Density = 0.5 kg / 5000 kg/m³ = 0.0001 cubic meters

This calculated volume represents the amount of space the object occupies and, consequently, the volume of fluid it will displace when fully submerged. To find the buoyant force, we calculate the weight of this displaced water. Given that the density of water is 1000 kg/m³, the mass of the displaced water is:

Mass of displaced water = Density of water × Volume = 1000 kg/m³ × 0.0001 m³ = 0.1 kg

The weight of this water, and thus the buoyant force acting on the object, is 0.1 kgf.

The apparent weight of the object while submerged is the result of its actual weight being partially supported by the buoyant force. It is calculated by subtracting the buoyant force from the weight in air:

Apparent Weight in Water = Weight in Air – Buoyant Force

Apparent Weight in Water = 0.5 kgf – 0.1 kgf = 0.4 kgf

Question 5.

Two spheres A and B, each of volume 100 cm3 is placed on water (density = 1.0 g cm−3). The sphere A is made of wood of density 0.3 g cm−3 and sphere B is made of iron of density 8.9 g cm−3.Find: The weight of each sphere, and The upthrust on each sphere. Which sphere will float? Give a reason.

Ans:

Analyzing the Wood and Iron Spheres

To understand how the wooden and iron spheres behave in water, we need to examine three key aspects: their individual weights, the upward buoyant force (upthrust) they experience, and how these forces determine whether they float or sink.

1. Calculating the Weight of Each Sphere

An object’s weight is the force of gravity pulling it downward. It is calculated by multiplying its density by its volume.

- Wooden Sphere (A):

With a density of 0.3 g/cm³ and a volume of 100 cm³, its mass is 30 grams. Therefore, its weight is equivalent to the force exerted by a 30-gram mass. - Iron Sphere (B):

With a much higher density of 8.9 g/cm³ and the same 100 cm³ volume, its mass is 890 grams. Consequently, its weight is equivalent to the force exerted by an 890-gram mass.

Summary: The iron sphere is significantly heavier, with a weight nearly 30 times greater than that of the wooden sphere.

2. Determining the Upthrust on Each Sphere

Upthrust, or the buoyant force, is the upward push exerted by a fluid. According to Archimedes’ principle, this force equals the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. The maximum amount of water either sphere can displace is 100 cm³, which has a mass of 100 grams.

- Wooden Sphere (A):

Since wood is less dense than water, this sphere will not sink completely. It will float, settling at a point where it has displaced just enough water to balance its own weight. Therefore, the upthrust acting on it will be exactly equal to its weight, which is equivalent to a 30-gram force. - Iron Sphere (B):

Iron is denser than water, so this sphere will sink and become fully submerged. It will displace the maximum possible volume of water (100 cm³). This results in the maximum possible upthrust, equivalent to a 100-gram force.

Summary: Despite its greater weight, the iron sphere only experiences an upthrust equivalent to 100 grams, while the wooden sphere, though lighter, is perfectly supported by a 30-gram upthrust.

3. Identifying Which Sphere Will Float

The key to flotation lies in the balance between weight (downward force) and maximum possible upthrust (upward force).

- Wooden Sphere (A): Floats

Its weight is equivalent to a 30-gram force, while the maximum upthrust available is a 100-gram force. Because the maximum upward push is greater than the downward pull, the sphere will rise and adjust its position in the water. It will float, with part of its volume above the surface, until the upthrust exactly matches its weight. - Iron Sphere (B): Sinks

Its weight is equivalent to an 890-gram force, but the maximum upthrust it can generate is only a 100-gram force. The downward force is overwhelmingly greater than the maximum possible upward force. This net downward force causes the sphere to accelerate to the bottom.

The Fundamental Reason: A Matter of Density

Ultimately, this behavior boils down to a simple comparison of densities. An object will float if its average density is less than the density of the fluid it is placed in.

- The wooden sphere has a density (0.3 g/cm³) lower than water (1.0 g/cm³), so it floats.

- The iron sphere has a density (8.9 g/cm³) higher than water, so it sinks.

Question 6.

The mass of a block made of certain material is 13.5 kg and its volume is 15 × 10-3 m3. (a) Calculate upthrust on the block if it is held fully immersed in water.

(b) Will the block float or sink in water when released? Give a reason for your answer.

(c) What will be the upthrust on the block while floating? Take density of water = 1000 kg m-3.

Ans:

(a) Calculate the upthrust on the block if it is held fully immersed in water.

The upthrust (or buoyant force) on an object fully submerged in a fluid is given by Archimedes’ principle. It is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

- Volume of the block, V = 15 × 10⁻³ m³

- Density of water, ρ_water = 1000 kg/m³

- Acceleration due to gravity, g = 9.8 m/s² (This is a standard value used unless specified otherwise)

Step 1: Calculate the mass of water displaced.

When fully immersed, the volume of water displaced is equal to the volume of the block.

Mass of water displaced = Density × Volume = ρ_water × V

= 1000 kg/m³ × (15 × 10⁻³ m³)

= 15 kg

Step 2: Calculate the weight of the water displaced (which is the upthrust).

Upthrust, F_b = Mass of water displaced × g

= 15 kg × 9.8 m/s²

= 147 N

Therefore, the upthrust on the block when fully immersed is 147 N.

(b) Will the block float or sink in water when released? Give a reason.

To determine if the block will float or sink, we compare its density to the density of water.

- Mass of the block, m_block = 13.5 kg

- Volume of the block, V_block = 15 × 10⁻³ m³

Step 1: Calculate the density of the block.

Density of block, ρ_block = Mass / Volume

= 13.5 kg / (15 × 10⁻³ m³)

= 900 kg/m³

Step 2: Compare densities.

Density of the block (ρ_block) = 900 kg/m³

Density of water (ρ_water) = 1000 kg/m³

Since the density of the block (900 kg/m³) is less than the density of water (1000 kg/m³), the block will float when released.

(c) What will be the upthrust on the block while floating?

When an object floats freely, it is in a state of equilibrium. The forces acting on it are balanced.

- The downward force is its weight (W = m_block × g).

- The upward force is the upthrust (F_b).

According to the principle of flotation, the weight of the floating body is equal to the weight of the liquid it displaces. Therefore, the upthrust must be equal to the weight of the block.

Step 1: Calculate the weight of the block.

Weight of block, W = m_block × g

= 13.5 kg × 9.8 m/s²

= 132.3 N

Step 2: Determine the upthrust.

Since the block is floating, Upthrust = Weight of the block

Therefore, the upthrust on the block while floating is 132.3 N.

Summary of Answers:

(a) Upthrust when fully immersed: 147 N

(b) The block will float because its density (900 kg/m³) is less than that of water (1000 kg/m³).

(c) Upthrust while floating: 132.3 N

Question 7.

A piece of brass weighs 175 gf in air and 150 gf when fully submerged in water. The density of water is 1.0 g cm-3.

(i) What is the volume of the brass piece? (ii) Why does the brass piece weigh less in water?

Ans:

(i) Finding the Volume of the Brass Piece

We are told the piece of brass weighs 175 gf in air and 150 gf when submerged in water.

The apparent loss of weight when submerged is a result of the upward buoyant force acting on the object. The magnitude of this buoyant force is exactly equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

- Weight loss in water: 175 gf – 150 gf = 25 gf.

This means the buoyant force acting on the brass is 25 gf. By Archimedes’ principle, this force equals the weight of the water displaced. Therefore, the weight of the water displaced is also 25 gf.

We are given the density of water as 1.0 g cm⁻³. Density is mass per unit volume, and since the gram-force (gf) is the weight of a 1-gram mass, we can work with mass directly.

- Mass of water displaced: 25 grams.

- Density of water: 1.0 g/cm³.

We can now find the volume of this displaced water using the formula:

Volume = Mass / Density

- Volume of displaced water = 25 g / 1.0 g/cm³ = 25 cm³.

When the brass is fully submerged, it displaces a volume of water equal to its own volume.

Therefore, the volume of the brass piece is 25 cm³.

(ii) Why the Brass Piece Weighs Less in Water

The brass piece weighs less in water because of the upward force, known as buoyancy, exerted by the water.

When the brass is immersed, it displaces a certain volume of water. The surrounding water pushes back against the object from all sides, but the pressure is greater on the bottom surface of the object than on the top due to the increasing depth of the water.

This upward buoyant force acts in the opposite direction to the downward force of gravity (the object’s weight). The scale reading shows the net force. So, when the scale reads 150 gf in water, it is measuring the object’s true weight (175 gf) minus the upward buoyant force (25 gf), making it seem lighter.

Question 8.

A metal cube of edge 5 cm and density 9 g cm-3 is suspended by a thread so as to be completely immersed in a liquid of density 1.2 g cm-3. Find the tension in thread. (Take g = 10 m s-2)

Ans:

A Walk-Through of the Floating Cube Problem

Let’s break down this physics problem about a cube suspended in a liquid. We’ll be meticulous with units, converting everything into the standard SI system (meters, kilograms, seconds) right from the start to keep things clean and avoid errors.